Edge of Valor (3 page)

Authors: John J. Gobbell

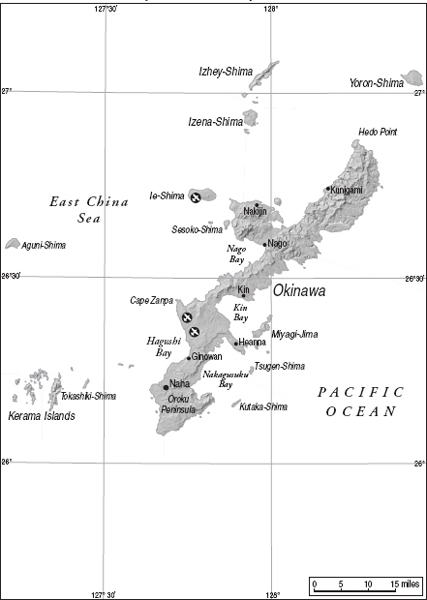

Greater East Asia, 1945

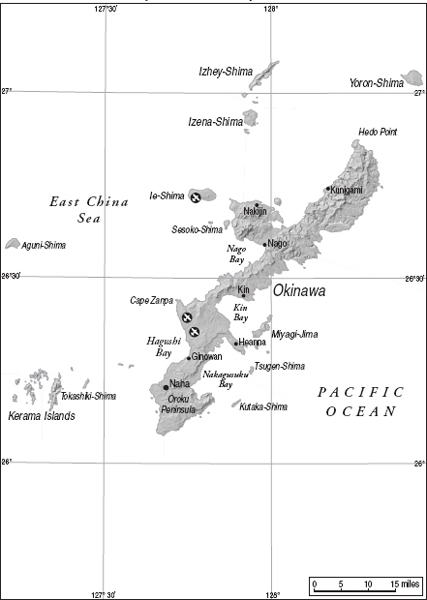

Okinawa Prefecture, Ryukyu Islands, Japan, 1945

Tokyo and Environs, 1945

At the height of a kamikaze raid off Okinawa in April 1945, Rear Adm. Arleigh Burke of the U.S. Fifth Fleet heard a voice transmission from an unidentified destroyer that had just been hit, killing all of her senior officers:

“âI am an ensign,' the voice said. âI have been on this ship for a little while. I have been in the Navy for only a little while. I will fight this ship to the best of my ability and forgive me for the mistakes I am about to make.'”

âE. B. Potter

, Admiral Arleigh Burke

We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation; the Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. But stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals. . . . Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights, shall be established.

âPotsdam Declaration, Article 5, Conference of the Allied Powers, Potsdam, Germany, July 26, 1945

9 August 1945

USS

Maxwell

(DD 525), Task Force 38, North Pacific Ocean, twenty-three miles east of Hitachi, Japan

A

lonely sun hung above the Japanese coastline as if governed by its own whimâit alone would decide when to set, and to hell with nautical predictions fabricated by mere mortals. The orange-red ball cast a miasma of reds and pinks around a circular formation retiring to the east, the day's deadly task now done. The group consisted of four cruisers and eight destroyers protecting the battleship

Iowa

in the center. Four F6F Hellcats, their combat air patrol, buzzed lazily overhead, watching, waiting.

The setting sun made everybody nervous. Bad things happened at sunset and sunrise. The desperate Japanese were hurling kamikazes after the Third Fleet. The damage had been great; ship after ship had been taken off the line for repairs; many had been sunk. Destroyers and carriers had borne the brunt. In many cases the destroyers, the “little boys,” had been crumpled into junk as if smashed by a giant fist.

The

Maxwell

was again at general quarters after a long day's work. The crew had stood at their battle stations during sunrise. Then, during the day, Task Force 38 had moved close to the Japanese mainland and the

Iowa

had hurled her 16-inch, 2,000-pound projectiles eight miles inland. Her target: the industrial section of Ibaraki Prefecture, where Hitachi Industries' electronics works were concentrated.

The

Maxwell

and the rest of the task force had been close enough to pump out a few rounds as well. But as they retired for the evening the destroyers readied their 5-inch guns for the kamikazes' deadly retribution. Gun crews struck the “common” ammunition with base-detonating fuses below into the magazines and pulled up antiaircraft projectiles with proximity fuses, stocking them in the

upper handling rooms for immediate use. Now they were once again at general quarters to defend against the raid that was certain to come.

Cdr. Todd Ingram paced his bridge, tugging at the straps on his life vest. The

Maxwell

had made it through so far. Whether by luck or Divine intervention or skillful fighting and maneuvering, Ingram couldn't say. After the protracted Okinawa campaign coupled with Admiral Halsey's triumphant bombardment of the coast of Japan, he was too tired to think about it. For the past four months he'd averaged five hours of sleep a day. Along with the rest of the crew he'd lived from meal to meal and watch to watch, becoming a near automaton.

But over the past three days a different feeling had crept over Ingramâand, perhaps by osmosis, over the crew as well. Something awesome and horrific had happened at Hiroshima. Rumors flew around the fleet. The war could be over. Expectations of surrender grew into dreamsâa good night's sleep, a week's worth of good night's sleep; a thick, juicy steak; plenty of beer; and course zero-nine-zero: home. But the good news didn't come; the pressure was still on. No sleep, no beer, no steak, no homeward trek; just more kamikazes and the incessant cracking of guns and the smell of cordite and the odor of death.

Lt. Cdr. Tubby White, the

Maxwell

's executive officer, clomped onto the bridge wearing khaki shorts, a T-shirt, and sandals. White had played guard at USC, but his well-muscled torso had grown to generous proportions since then; thus his nickname. White's inverted belly button poked through his sweaty T-shirt. As exec, White's general quarters station was two decks below in the combat information center (CIC), a dark, cramped space full of heat-generating electronic equipment such as radar repeaters. There was no air conditioning.

Ingram and White had known one another since the Solomon Islands campaign of 1942â43 when they had served in the destroyer

Howell

. The

Howell

was sunk, and White went on to successfully command a PT boat in the Upper Solomons campaign and then a squadron of PT boats during General MacArthur's return to the Philippines. The Philippines campaign was just about done. PT boats were no longer needed, and Lt. Cdr. Eldon P. White was on the market, so to speak. Ingram scooped him up in an instant.

White walked up, waving a flimsy.

“What is it?” snapped Ingram.

White tucked the message behind his back. “Touchy, touchy.”

“Damn it, Tubby, I don't have time forâ”

Capt. Jerry Landa walked up and snatched the flimsy from behind White's back. “Insubordination, Mr. White.”

White drew up to a semblance of attention. “Sorry, Commodore.”

Ingram turned aside, trying not to laugh. These two had been at it for years. But they were so similar. Although Tubby White was heavier than Landa, their configurations were the same: portly. But Landa, with dark wavy hair, was far more handsome and sold himself to others with a winning smile, the main

feature being upper and lower rows of gleaming white teeth. A pencil-thin mustache on top was designed to draw in the ladies and more than adequately did its job. The son of a Brooklyn stevedore, Landa went to sea at fifteen and worked his way up, obtaining his master's license at the age of thirty. At the war's outbreak, he immediately transferred to the U.S. Navy and a life on destroyers. He soon found himself in command, and it suited him well. A fearless and solid leader at sea, the unmarried Landa was flamboyant when ashore, doing more than his share of drinking. Often, junior officers were tasked with carrying their commanding officer back to the ship, where they pitched him into his bunk to sleep it off. Over the years Landa had acquired the nickname “Boom Boom,” presumably because when the party had shifted to third gear, he would stand on a chairâor whatever was convenientâand tell barroom jokes mimicking the sounds of human flatus. Oddly, Landa didn't like to be called “Boom Boom,” although he enjoyed calling others by nicknames.

Ingram, on the other hand, came from Echo, a small railroad and farming community in southeastern Oregon. Not muscle bound, Ingram still had an athlete's frame and weighed an efficient 187 pounds. He had sandy hair, and his deep-set eyes were gray with a touch of crow's feet in the corners, the result of lonely hot summer days in the endless wheat fields of eastern Oregon. A broad, disarming grin delivered from time to time was characterized by a chipped lower tooth, the result of a fall off a combine as an eleven-year-old. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1937, he escaped the “Battleship Club” syndrome and went to small ships, initially minesweepers, where he rose to be the young skipper of the minesweeper USS

Pelican

(AM 49) by war's outbreak in 1941.

While others at home were still trying to overcome the shock of the Pearl Harbor attack and the devastating Japanese conquests in the Far East, Ingram was seeing the horrors up close. One of the worst was when the

Pelican

was bombed out from under him in Manila Bay in April 1942.

As different as they were, Ingram, Landa, and White had at least one thing in common: utter exhaustion. They were dead tired. None had slept more than three or four hours at a time over the past three months. There were dark pouches under their eyes, especially Landa's, and the skin on their faces had a grayish pallor and sagged. The corners of their mouths turned down and their eyes were more often than not bloodshot.

But for now, Ingram forgot their predicament as White and Landa glared at one another for a moment, reliving a heated argument that began in the days on the

Howell

when Landa had been the skipper and Tubby White a lieutenant (jg). Ingram was sure both had forgotten what started the argument and now merely relished mutual efforts to antagonize each other. The rancor grew worse when Tubby White openly referred to CIC as the Chaos Information Center, a joke that Landa would have gladly told himself had it not come from White.