Edie (39 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Edie at the Warhol exhibition, Philadelphia, 1965

While this was going on, an architectural graduate was trying to break through the fake ceiling above us so we could get out through the library private stacks, over the roof, and down the fire escape and out where the police could protect us. He was up there on the floor above with crowbars, ripping up the floor. That’s how we escaped.

Edie was astonishing. She was really in show business, giving all those people something to look at . . . and it was crucial because they had been getting more and more unruly for hours, angry, first of all, because there were no pictures on the wall. So she, in fact, became the exhibition. Andy was just terrified, white with fear. Edie was scared to death but she was adoring every minute. She was in her element. She carried on this sort of forty-minute soliloquy into the microphone. She called out to them, “Oh, I’m so glad you all came tonight, and aren’t we all having a wonderful time? And isn’t Andy Warhol the most wonderful artist !”

PATTI SMITH

I went to Philadelphia to Warhol’s opening at the museum. I came in from south Jersey on a train and I guess we took the bus. To me it was like slitting open the belly of a discotheque and walking in. Edie was coming down this long staircase. I think she had ermine wrapped around her; her hair was white, and her eyebrows black. She had on this real little dress. I think she had these two . . . unless I dreamed it . . . big white afghan hounds on black leashes with diamond collars, but that could be fantasy. It was all like being shot up. She seemed so connected. That’s why I thought she was great. She had so much life in her. Her movement was fluid, and she was like little queenie.

People think it’s all superficial, but I thought and stI’ll do that my consciousness about it was great. I always thought that the world of the upper class was really fantastic. I was from a working-class family with no affiliation ever with the middle class. So I really didn’t resent the upper class. I thought they were great, their style, and the way they moved . . . and Bergdorf s. I thought Edie was great. I even had a crush. I wasn’t into girls or anything, but I had a real crush on her.

ONDINE

There’s no way people can stand outside a museum and chant “Edie and Andy.” But they

were

out there, chanting and screaming. They were

that

relevant.

Edie told me afterwards: “Ondine, I cannot believe that they were out there chanting “Edie and Andy! Edie and Andy!’” She said it was like an insane response from a whole culture. I said, “Well, that’s what it is. These people are relating to you for a very good reason.” If you’re going to be that kind of culture hero, my

God!

Assume the mantle. Wear it! Be the culture hero. Edie was, literally, the queen of the whole scene. Totally the best of them all.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

At first our father adored Edie’s publicity. I’ve seen a letter in which Fuzzy refers to her as a Youthquaker—a phrase out of

Vogue:

“Edie is 22, going whither, God knows, but at a great rate!” But still, he lapped it up. He hoped she really would become an important actress.

Did you know Fuzzy actually met Andy Warhol at the River Club in Manhattan? Edie arranged it. Ernest Kolowrat would remember what happened. He was a kind of literary witness to the Sedgwicks . . . an audience. Ernie adored Fuzzy. He once said he’d love to marry Edie so he could live happily ever after and see Fuzzy.

ERNEST KOLOWRAT

At the River Club that evening Edie kept getting up from the table throughout dinner to telephone. Finally I asked, “What the hell’s going on?" Fuzzy said, “Oh, she’s trying to get Mr. Warhol to join us.” It was a sudden brainstorm of Edie’s that Fuzzy should meet Andy. It was the night of the Floyd Patterson-Cassius Clay fight in Las Vegas when Clay really taunted Patterson and made him suffer. Fuzzy was standing by the bar downstairs off the dining room watching the fight on television and flinching with every punch.

I remember two remarks Fuzzy made about Andy Warhol while we were all waiting. At about ten-thirty in the evening, when he stI’ll hadn’t

shown up, Fuzzy asked, “Do you suppose Mr. Warhol has had his breakfast yet?” Another one was: “Do you suppose the doorman should be told about him so hell be let in?” Fuzzy wasn’t specifically teasing Edie. I think it was sort of like whistling in the dark because he was nervous. Andy represented a threat and challenge at the same time. Fuzzy was a conservative, and the idea that perhaps Andy was sleeping with his daughter was very disturbing to him.

Fuzzy and I discussed the injustice of somebody like Warhol hitting it just at the right time with a good gimmick while Fuzzy was out on the ranch painting and sculpting wonderful stuff in a classical manner and not getting the recognition he should have. I think Fuzzy understood it, and outwardly he was never bitter. When he talked about it, he always smiled. But I knew that, inside, it was biting at him. I always thought the tragedy of his life was that he should have been the President of the United States, and when he settled on the more specific goals of painting, writing, and sculpture, he had a much more specific disappointment in not being adequately recognized in those fields. He was an immensely sensitive man who was being torn apart by what was happening. So you can imagine what an effect Andy Warhol’s arrival must have had on him—when the gray eminence finally arrived.

Edie brought him in and introduced them. Andy shook hands very limply, very weakly. Fuzzy was very generous, awfully nice. Tried to get him drinks . . . Andy this and Andy that. Andy didn’t say anything. He whispered a few things to Edie. The River Club, with that wonderful view of the East River, was very much Fuzzy’s turf, and that made Andy very uncomfortable. I don’t know whether he shakes all the time. Does he? Well, he was very nervous. Quivering. After the first five minutes Fuzzy didn’t say much to Andy, he kind of gave up. We sat around chatting for about twenty minutes. Then Edie spirited Andy out of there—she said it was too much for him. Afterwards Fuzzy and I were standing at the bar and he said to me with a great sense of relief: “Why, the guy’s a screaming fag. . . .”

Edie was very nervous that night. It was a tremendous event in her life, and I suspect in Andy’s it was . . . almost devastating, meeting Fuzzy on his home ground. For anyone as internalized as Andy, someone as externalized as Fuzzy must have been very threatening.

ANDY WARHOL

The father was so handsome. He was telling us about these sculptures that he was doing—a big horse or something like that. Edie was happy to see him. It wasn’t really anything that different. It was really nice. She was always saying funny things about him, but he seemed really great. He was, I guess, the most handsome older man I’ve ever seen. She might have said he was sick with something . . . I couldn’t believe her. People always say things and you don’t know if they’re true or not.

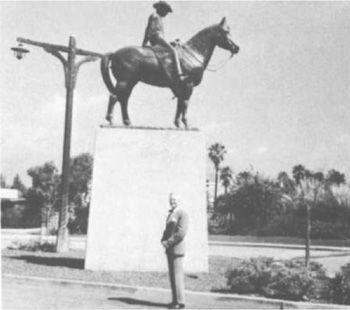

Francis Sedgwick with his cowboy statue

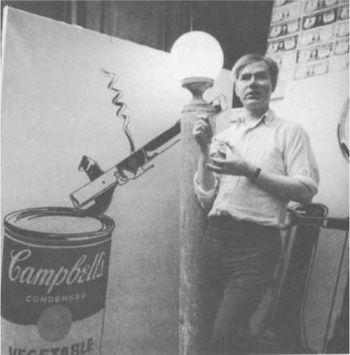

Andy Warhol in his studio

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Edie was looking for an alternative. Andy Warhol was a kind of alternative convention. She said once that she didn’t understand why our parents felt so threatened: she wasn’t doing anything against them, she just wanted to find a new way of life, not

their

way of life.

But her “new life” became, in a bizarre way, a reflection of many of the features of her life with my mother and father. It revolved around a dangerous, powerful man who was in control of everything in sight and who dictated the style: We do this, we don’t go to that; we go to these places, we don’t go to those places; this is where we are secure and those people out there don’t exist. Even the inversion of the sexual theme was mere. Edie felt a strong sexual relationship to our father. But it was impossible. The same thing was true with Warhol. It was impossible. He was androgynous, as Edie herself was. A kind of perverse Peter Pan.

I don’t know if Edie really understood that Andy and his ilk were going to inherit the earth. But intuitively, she must have felt that it was possible. My father’s world stI’ll had tremendous power because of convention and tradition and so forth, although his art had been out since Daniel Chester French. But once you said: “Well, that’s not the way it is, and that’s not the game, and those are not the rules—after all, we’re all just people,” that must have been a hydrogen bomb to my father! That rejection of rhetoric, that deadly banality made Andy a final weapon against my father. There was no way my father could get to Andy Warhol.

JOEL SCHUMACHER

There were other father figures in New York at that time—the acid doctors. A friend of mine—well, an ex-friend of mine—told me about this terrific doctor where you’d get these vitamin shots—Dr. Charles Roberts. I used to run into Edie there. I went one night, got this shot, and it was the most wonderful shot in the world. I had the answer: I mean, it gives you that rush. There were vitamins in it, and a very strong lacing of methedrine. I’d never heard of methedrine or speed. They never told you what was in the shot anyway. It was a slow evolution. I went there first and got a shot. I went a week later and got another one. And maybe one week later I was feeling kind of down, and I went twice a week. Eventually I was going there every day, and then I was going two or three times a day. Then I went four times a day. Then I started shooting up myself.

Dr. Roberts was the perfect father image. His office, down on Forty-eighth Street on the East Side, was very reputable-looking, with attractive nurses, and he himself looked like a doctor in a movie. He was always telling me of his wonderful experiments with LSD, delivering babies, curing alcoholics . . . and he was going to open a health farm and spa where all this was going to go on . . . and naturally he was stoned all the time, too. He wasn’t a viper. I just think he was so crazy, he truly thought he was going to help the world. He wasn’t out to kI’ll anyone.

We

were the ones going in and getting the shots. I

mean, anyone can set up a booth on the side of the road reading: I’m giving arsenic shots here, but

you

have to stop and take them.

Over the years that he was riding high, tons of people went to see Dr. Roberts. But there was a little crowd of favorites. When you were a favorite, it meant that you were allowed special privileges. Even if the waiting room was filled with twenty people, you got right in. When you were addicted, being able to get right in was very important. You got bigger shots; you got shot up more than anybody else, and you became more of an addict. It was wonderful to be part of this special group. Edie fit right in. The minute she hit there, she became a special Dr. Roberts person.

I’ll give you a description of what it was like to go to Dr. Roberts. The time is two-thirty in the afternoon. I’m going back for my second shot of the day. I open the door. There are twenty-five people in the waiting room: businessmen, beautiful teenagers on the floor with long hair playing guitars, pregnant women with babies in their arms, designers, actors, models, record people, freaks, non-freaks . . . waiting. Everyone is waiting for a shot, so the tension in the office is beyond belief.

Lucky you, being a special Dr. Roberts person who can whip right in without waiting. Naturally, there’s a terribly resentful, tense moment as you rush by because you’re going to get your shot.

You attack one of the nurses. By that I mean you grab her and say, listen, Susan! Give me a shot!” You’re in the corridor with your pants half off, ready to get the shot in your rear. Meanwhile Dr. Roberts comes floating by. Dr. Roberts has had a few shots already, right? So in the middle of this corridor he decides to tell you his complete plan to rejuvenate the entire earth. It’s a thirteen-part plan, but he has lots of time to tell it to you, and as the shot starts to work—Susan having given it to you—you have a lot of time to listen.