Editors on Editing: What Writers Need to Know About What Editors Do (38 page)

Read Editors on Editing: What Writers Need to Know About What Editors Do Online

Authors: Gerald Gross

Spotting the trends that will prevent you from spending a lot of time writing in the wrong genre is half the battle. But another development—the decline of paperback

reprint

publishing—may create additional opportunities for writers who want to start out in paperback. Nine years ago, I spoke of the dual function of the paperback editor as both an editor of original manuscripts and a reprint editor, i.e., an editor who acquires paperback reprint rights to hardcover books published at other houses. I tried to describe the special pleasure of reprint editing—which is not unlike the excitement a journalist experiences when he finds the next scoop—combining a hardcover publisher’s catalog for the book that could become, in its reprinted version, a huge paperback best-seller. Many books “born to be a paperback” were acquired via the reprint route, and the reprint side of a paperback editor’s job was considered so important that many paperback editors did nothing but acquire reprint rights. Their job was to totally “cover” the hardcover house, to know exactly what was going to be published by each one, and to convince the hardcover subsidiary rights director from whom they would buy the rights that their paperback house was the best paperback publisher for the book. These paperback reprint editors were charged with establishing strong contacts with the hardcover houses they covered so as to be in a position to set the all-important paperback floor bid on a hardcover book, which allowed the paperback house to top the final bid in any future auction for reprint rights. If a paperback editor spent his morning working on an original lead-title manuscript, more than likely in the afternoon he’d be on the phone with a rights director keeping tabs on future reprint possibilities.

But for the past nine years, the reprint market in paperback publishing has gotten smaller, as hardcover publishers work more closely than ever with their own paperback subsidiaries and retain rather than sell paperback

rights. Authors and agents gradually decided that it made no economic sense to pursue the traditional reprint agreement, because by contract the hardcover house sold paperback rights but had the benefit of sharing in the author’s future paperback royalties. But now, in the so-called hard-soft deal, authors do not have to share their paperback royalties with anyone, since the hardcover and paperback publisher are the same entity. Publishers encourage hard-soft deals because they keep the control of the future paperback publishing in the hands of one house, as opposed to casting the paperback to the winds of fate elsewhere. And authors like them because if one company controls the total publishing plan, there’s a sense of continuity in the author-publisher relationship.

…

The net effect of all this for paperback editors is to put them largely out of the reprint publishing business. Since there are obviously fewer opportunities to bid on paperback rights (for example, major paperback auctions used to be a weekly occurrence in the mid-1980s; now they hardly occur at all), paperback editors are under greater pressure to develop

original manuscripts

, which is good news for writers looking for more opportunities. In earlier years, a paperback editor had a more balanced work load of originals and reprints—and a deeper pool of potential paperback best-sellers. Now paperback editors spend more time looking for original material, creating the possibility of greater demand for paperback originals.

If this is indeed good news, what can you expect in your dealings with a paperback editor if you choose to go this route? In what respects is working with a paperback editor different from working with a hardcover editor? Is there, in fact, any difference at all? The answer is that there’s beginning to be no difference in the working relationship. When hardcover and paperback houses were completely separate—either as different corporate entities or as separate subsidiaries under their own corporate umbrella—the hardcover editor acquired the book, worked with the author, and edited the book. The paperback editor, one floor below, generally had very little editorial input. His responsibility was simply to reprint the book and to map out the paperback publishing and marketing strategy. But this “upstairs/downstairs” relationship is changing at many publishing companies, most notably at houses such as the Putnam Berkley Group, which realized that many of its Putnam hardcover best-selling authors were coming to the house via its Berkley paperback editors, authors like Tom Clancy, LaVyrle Spencer, and W. E. B. Griffin. Paperback editors have helped bridge the traditional gap between hardcover and paperback subsidiaries. In the day-to-day working relationship between a paperback editor and his author, all the traditional steps in editing and publishing take place. And since the

book is brought in by the paperback editor, if the author ever goes into hardcover, the author generally stays with his original editor.

Let’s look at some examples of how paperback editors work with authors. Say the publisher has decided that the house would like to publish a lead-level paperback original, a historical saga about the opening of the American West by a first-time author who, on the basis of an outline and sample chapters, has convinced the publisher that he has a great story to tell, that the historical detail is just right, and that the author himself is a potentially promotable writer who is an expert on the American West. Once a proposal and sample chapters are bought, the editor would write a preliminary editorial letter suggesting that perhaps one of the main characters needs a stronger role in the story. Say the book is going to be about a man and wife who together form the beginning of a powerful family dynasty, moving westward to make their fame and fortune in Gold Rush California. But the wife in the story—a potentially wonderful character—seems underplayed in the early chapters. In this instance, the paperback editor would alert the author to this in the letter, thereby suggesting an important point about the overall future direction of the book. If the author always suspected that this was a weakness in the story line, having this pointed out to him by the editor is reassuring, since the author now feels that he and the editor share the same vision of the book.

The author then delivers a completed manuscript a year later—and major editorial work would begin, with an extensive revision letter pointing out the larger structural elements that still need attention. Perhaps there is an underdeveloped subplot between rival sons in this family saga; or the overall proportion of the book is slightly off, as the author spends too much time preparing for the family’s departure from Independence, Missouri; or there’s a notable absence of historical detail in the Indian sections of the book; or characters sometimes talk as if they were in a drawing room in 1876 New York City instead of on the 1876 frontier. All these concerns would be addressed in the revision letter, stating the editor’s excitement and enthusiasm for the book, but tactfully suggesting areas that would help the author realize the book’s full potential. Buoyed by this constructive advice—and the gut feeling that he is working with a diligent editor who has done his homework and really cares—the author goes back to his word processor, strengthening some characters here, shading in the historical detail there, or speeding up parts of the story as suggested by the editor.

Then the second draft comes in and the excitement begins. A terrific book has been written, and both author and editor know it. Now all that remains to be done is some light line editing on the manuscript itself—perhaps, in this case, on the dialogue, which needs some fine tuning. Here’s where some

actual blue pencil editing on the manuscript takes place, all of it subject to the author’s approval. Then there might still be a few questions from the editor regarding some internal inconsistencies in the book, pointed out to the author often with query tags attached to the margins of the manuscript. And then, after the author has approved the line editing and answered the editor’s queries, the book is ready for the copy editor and transmitted to production. What the paperback editor and his author realize is that their constructive, collegial editorial relationship has been focused on one goal—to bring out the best the author can offer. Although they may have disagreed on a few points, the final manuscript is the product of an author’s trust in his editor, a solid foundation for the challenges ahead in selling the book not only to the publisher’s own sales force, but finally to the fickle customer browsing the paperback racks.

And, needless to say, there are a lot of challenges in launching the marketing campaign for a successful lead title as a paperback original. In my earlier essay, I spoke of the difficulty of getting review attention for paperbacks, and this is still largely true. But I’ve come to learn that review attention is not totally relevant to the success or failure of a paperback original. The main goal is that the book be taken seriously by the sales reps since they will be selling an unknown quantity, so to speak, a book without any previous sales history in a hardcover edition. One of the ways paperback editors do this is to solicit endorsements for the book from other best-selling authors. Although this practice is sometimes overdone, getting quotes helps position the book. The manuscript itself is another “selling” tool for generating excitement among the sales force. If the book is being described as an epic western saga in the tradition of James Michener and Louis L’Amour, sending sales reps bound galleys or a special reader’s edition is very effective, particularly if some advance quotes are emblazoned on the cover. And the cover itself, foiled and embossed for eye-catching appeal, with a beautiful illustration grabbing the reader’s attention, becomes another critical selling tool.

Finally, the author himself may be the book’s “best seller.” One effective method is the paperback solicitation tour, where the publisher sends the author out to meet key accounts around the country. Sometimes this takes the form of brief wholesaler “driver” breakfast meetings in which the author meets the paperback book buyers, the people who will eventually place the orders, as well as the truck drivers who call on individual accounts, checking stock and making sure this new paperback original gets prominent display. If the major accounts and their employees have read the deluxe bound galleys, have gotten a tee shirt with the name of this new saga emblazoned across the front of it, and have enjoyed meeting the author at one of their breakfasts, those buyers and drivers will order the book in

substantial quantities, remember when it comes out, and ensure that it is displayed for maximum sales. By this point the editor has been not only editorial manager of the book, but also its in-house impresario, rolling up his sleeves to become a multifaceted marketing expert, well versed in all the methods of selling paperback books, and able to speak to his marketing people so that they, in turn, can successfully make the book a roaring success.

…

Having read all this, do you still want to be a paperback writer? Isn’t there that nagging question, “Won’t I be taken more seriously if my first book is published in hardcover?” Well, it’s time to lay to rest the notion that authors have to begin their careers in hardcover, or that it’s necessarily more desirable to do so. If reviews are the most important thing to you—if critical acclaim is what drives you to write in whatever genre you’ve chosen—go hardcover first. Even nine years after writing my first essay, paperbacks still have a long way to go before they get the review attention they deserve. So if you’ve written a novel about a young man’s coming of age in the Midwest in the 1950s, and your book will have to be nurtured by the review media and hand sold by independent booksellers, hardcover is the right place for you. That’s how Anne Tyler got started; and if she’s your literary role model, my words won’t convince you to make your publishing debut in paperback. But if you’re working the territory of the so-called commercial authors who generally dominate the top ten spots on the bestseller list by writing in the mainstream genres, you can get to where those authors are by starting out in paperback. Best-selling authors such as Danielle Steel, V. C. Andrews, Janet Dailey, and W. E. B. Griffin built their readerships in paperback, and it can be argued that by seeding the market with their successful paperback books they built legions of loyal readers who stayed with them when they finally went to hardcover.

But you still might ask, “Why do I have to take the time to build a readership? Why not go for broke right now with a hardcover? What if I’ve written a terrific courtroom drama, and I think I could be the next Scott Turow?” Well, the answer is, not much

will

happen if your terrific courtroom drama ends up as a midlist 15,000-copy hardcover, with very little advertising, promotion, or publicity support, damaged further by having to compete with other hardcover first novels on a publisher’s overcrowded list. But what if, instead, the manuscript of that same book falls into the hands of a paperback editor who tells the literary agent that he loves the book, that the main character, a young prosecutor in Los Angeles, could be a continuing character for future books, and that the editor is so enthusiastic about it that he’d like to publish the book as the No. 1 title on his paperback

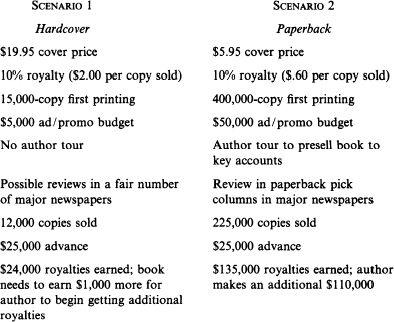

list. Now the author has to ask, do I want a 15,000-copy midlist hardcover, or an estimated 400,000-copy lead title in paperback? Here are the possible scenarios in greater detail of what might happen if the same book were published differently.