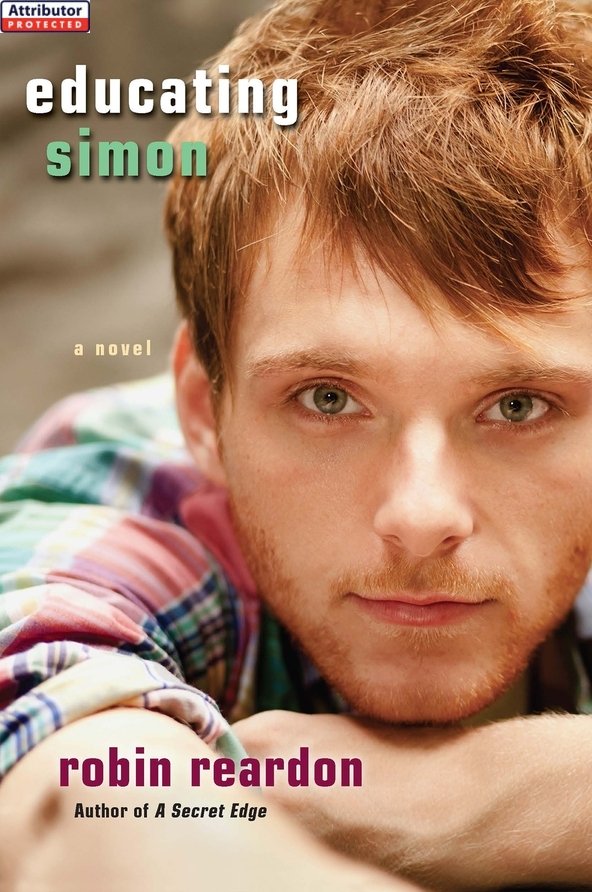

Educating Simon

Authors: Robin Reardon

Books by Robin Reardon

Â

Â

A SECRET EDGE

THINKING STRAIGHT

A QUESTION OF MANHOOD

THE EVOLUTION OF ETHAN POE

THE REVELATIONS OF JUDE CONNOR

EDUCATING SIMON

Â

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

Robin Reardon

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

-

Exile

Boston, Day Two, Sunday, 26 August

Boston, Day Three, Monday, 27 August

Boston, Day Four, Tuesday, 28 August

Boston, Day Five, Wednesday, 29 August

Boston, Day Six, Thursday, 30 August

Boston, Thursday, 6 September

Boston, Sunday, 9 September

Boston, Tuesday, 11 September

Boston, Wednesday, 12 September

Boston, Saturday, 15 September

Boston, Friday, 21 September

Boston, Saturday, 22 September

Boston, Sunday, 23 September

Boston, Sunday, 30 September

Boston, Sunday, 7 October

Boston, Sunday, 14 October

Boston, Sunday, 21 October, 2:00 a. m.

Boston, Sunday, 21 October, Addendum

Boston, Monday, 22 October

Boston, Sunday, 28 October

Boston, Sunday, 4 November

Boston, Saturday, 10 November

Boston, Sunday, 18 November

Boston, Monday, 19 November

Boston, Tuesday, 20 November

London, Thursday, 22 November

London, Friday, 23 November

London, Heathrow, Saturday, 24 November

Boston, Monday, 26 November

Boston, Tuesday, 27 November

Boston, Friday, 30 November

Boston, Sunday, 2 December

Boston, Tuesday, 4 December

Boston, Friday, 7 December

Boston, Friday, 21 December

Boston, Tuesday, 1 January

Boston, Sunday, 13 January

Boston, Thursday, 17 January

Boston, Sunday, 20 January

Boston, Wednesday, 23 January

Boston, Friday, 25 January

Boston, Sunday, 3 February

Boston, Thursday, 7 February

Boston, Sunday, 31 March

Boston, Tuesday, 30 April

Boston, Sunday, 5 May

Dedicated to the City of Boston

and to everyone whose life was changed

by the Boston Marathon bombing

on April 15, 2013

Do you know what you wish?

Are you certain what you wish is what you want?

If you know what you want, then make a wish.

Â

âCinderella's mother,

Into the Woods

(Stephen Sondheim)

Â

Â

Your silence will not protect you.

Â

âAudre Lorde, poet, writer, activist (1934â1992)

Worlds Destroyed

Yeah, I know. I have to colour it out for you. I'll do it a few times, but after that you can refer to the chart I've provided for you in the appendix of this journal.

Â

Terra cotta =

O

; Coral =

N

; Lilac =

E

Â

ONE. As in entry number one.

And you might ask, “Why are you bothering to number the entries at all when you're lying in hospital with your wrists tied up in bandages? Will there even

be

a Two? And whom do you think you're writing to, anyway?”

Good questions.

That first one was a short entry. Lots of reasons why. For one, I don't feel much like telling anybody anything right now, so when the hospital shrink comes in and does his best to make me talk, it's exhausting, so I also don't much feel like going on about anything afterwards.

For another, all I have is my mobile phone, and whilst I'm great at texting, it's a lot more trouble than typing. Which is what I'll have to do with this . . . this composition when I get home. If I ever get home. And if I ever feel like continuing this journal.

I'm home. For now. And whilst I've finished typing the notes from my mobile into my laptop, I can see that they look pretty pathetic on a full screen. Not much there. Rather like my life.

Didn't use to be that way. I'm fairly sure I remember a time when life was good, when my mum and dad and my cat and I were a family, when I was doing really well at Swithin Academy. In fact, I was doing so well that Dad once told me, “Not too early to be setting your cap at Oxford, Simon. Oxford is blue, you know. Blue for wide open skies.”

To which I replied, tongue-in-cheek, because this was a kind of running joke with us, “It's terra cotta. But that's fine, because that's an earth colour, and I'll need a good foundation.”

I think I was maybe fourteen when he said that. A couple of years ago now. And a few months before he died.

Â

Sorry; can't really talk about that. Needed a break.

Maybe I can talk about the good parts. There were a lot of them between my father and me. For one thing, I have Tinker Bell because of him. When I was thirteen I said I wanted a pet, and Mum suggested a corgi, probably because she likes dogs better than she likes cats. But Dad smiled at me and shook his head. He knew. And he took me to pick out a kitten, a British shorthair, with thick, plush fur and a round, wise head and big eyes that miss nothing. She's a sweet, intelligent cat. I named her Tinker Bell.

My dad and I used to go to church together. Mum was never that interested, but Dad and I would go almost every week, either to our usual (St. Cyprian's) or, if we wanted something special and planned ahead, we'd go into town to Westminster or St. Paul's. Dad used to tease me that if he'd gone into the priesthood as he'd planned, I wouldn't be around. As an Anglican priest he could still marry, of course, but my mother wouldn't have married him.

I took the church quite seriously when I was younger, and over Sunday dinners Dad and I would sometimes go over the sermon we'd heard that morning, teasing apart the Holy Word in a way that brought it into real life, our own lives. But I had begun to question my faith not long before my father died. I was starting to ask questions to which there are no good answers, and the more people I asked, the more disparate, fumbling answers I heard. Dad at least admitted that we don't have all the answers, but it seems to me that if God wanted us to take Him seriously, He would have made things clearer. It also seems to me that if the message of Jesus was so all-fired important, it should have been clear from the very start. What about all those people who lived before Jesus was born? If Jesus was really the one true Path, then why the hell didn't the Jews hear from him sooner? Why didn't everyone? For that matter, what about all the people who never heard about Jesus, through no fault of their own, because they lived inâI don't knowânorthern Germany in 75 C.E.? Or in ignorance in Iceland centuries after Jesus was supposedly resurrected? And those are just the most obvious questions.

There I go, capitalising the pronouns. It's automatic. I'll stop, because after I lost my faith I realised I might be an atheist. And when my father was killedâthat's right, he didn't just dieâwell, that was it. Quite obviously there was no God of mercy looking out for him, or for me or Mum, on that day.

As for how he diedâwell, I'm not going into that right now.

Bad enough

that

he died. But then to have one of my idiot classmates ask if maybe the reason was that God was punishing me for my lack of faith . . . I nearly flattened him. I admit to a certain amount of arrogance, but I'm not self-centred enough to think God would kill anyone, let alone someone like my father, to punish me. No God worth worshipping would do such a thing.

But enough of that.

One of the best things about being with my father was this condition we share. I almost certainly got it from him, along with my red hair. The special condition is synaesthesia. Most people don't even know what it is. And people who have it don't all experience it the same. My dad and I see letters as having colours. Each letter always has the same colour, but my terra cotta

O

is . . . was . . . blue to my dad. His sister, my Aunt Phillippa, sees colours when she hears music. I don't much like Aunt Phillippa, but I kind of wish I could see colours with music, too.

I wouldn't give up being a synaesthete for anything. I'm actually very smartâIQ of one-sixty-three and the vocabulary of an intelligent adult twice my ageâbut when I was younger, what impressed the other kids in school was that I could spell anything I'd seen at least once. The whole word takes on the colour of the first letter, really, but the other letters retain some of their own colour too. In the case of

Oxford

âwith two terra cottas, a dove grey

x,

a pale green

f,

a bright red

r,

and a dark brown

d

âthe other letters don't do much to modify the first letter. But take another word, and the effect is different.

England,

for example, is lilac, coral, fuchsia, bright orange, pale yellow, coral, dark brown. The whole word takes on a lilac tint, but I can still see the orange and yellow and brown. If you changed one of the lettersâsay, bright blue for

t

instead of brown for

d

âI'd know it was wrong right away, and my fabulous memory would tell me why.

I can hear you say, “So what? If I saw

England

spelled

Englant,

I'd know it was wrong right away, too.”

But consider this. Would you know immediately that

Nuefchatell

is misspelled, and why? Or

Cairphilly?

Caerphilly. Don't get me started. Don't talk to me about anything having to do with Wales.

Simon.

Blood red, bright yellow, brick red, terra cotta, coral.

Blood red, overall. I think maybe that's why slitting my wrists would have been my method of choice.

True confession time. That was not a typo, to say “would have been.” I didn't actually do it. I was sitting on the closed toilet seat, contemplating how warm the water should be whenâifâI turned it on, and I was staring at the razor blade I held between the thumbs and forefingers of both hands. I stared and stared until my vision got a little blurry and I began to feel faint. I slid to the floor and leaned against the wall forâI don't know, maybe ten minutes? And then I set the blade down. To be honest, I don't really know why I didn't go through with it. I do remember thinking that there would always be razor blades.

I'd sat there, giving myself a little time, drawing a mental picture. I remember thinking there would be rather a lot of blood. Red. Bright red blood. The bathwater would be full of it, swirling in beautiful shapes that I expected would be the last thing I would see. I pictured my mother finding me there. She'd scream, perhaps call my name a few times, maybe even try to lift me out of the water. And then she'd phone for help.

After that my story takes a split. One line ends up with me dead, buried in the soil of the land I refused to leave, despite my mother's plans. The other sends me to hospital. Imagine my consternation when I wake up there, head pounding, totally parched, and heavy white packs on both wrists.

I think I would scream. I know I would want to. I'm not one of those people who would send out a “cry for help.” (How I hate that expression.) It would've been real, that suicide, if I'd done it.

And I suppose you'll want to know why I was even poised to do it. Whether I wrote a note. Whether I thought it would hurt anyone when they found out. If I didn't feel loved. If I felt life wasn't worth it. If it was because I'm gay.

Well, I didn't write a note. For one thing, what would it say? “Mum, I can't believe you've done this to me. Dad would never have done anything like this if it had been you who died.”

For another, not everyone is capable of appreciating how well I write. The last thing I would do is leave my final words to be judged, picked apart, criticised after I'm gone by people who wouldn't know good writing if it fell from the sky, with or without colours.

And it wasn't because I'm gay. I have no problem with

that,

thank you very much. Even though I haven't told Mum yet.

So what did she do that was so horrid, you ask?

Here's what she did. She fell in love with a man, an architect, from Boston, Massachusettsâthat's bad enough. He was here in the UK to dig up (not really; couldn't resist) some Welsh ancestors inâguess where? Caerphilly. So he's not only from Boston, but he's also Welsh. Worse still. And Mum has married him! Severe punishment indicated for this transgression.

Sorry. I'm sure this is getting tedious. Maybe I'll just leave some kind of blank space when I have to shut off the laptop and go scream into my pillow, instead of starting new entries every time. It's also, no doubt, getting tedious to see the entries coloured out. So I'll stop that, too. I think you get the point, anyway.

Just so we're clear, though, understand that even though

b

is sky blue and

r

is bright red, it's only coincidental that each of those main colours begins with the letter in question. G is not green, as it happens. It's fuchsia. I refer you again to the appendix.

So, back to the break that ended the last entry.

Â

Trying again.

And she's making me move with herâwith themâto Boston.

I'm trying not to hate her. Truly. I never used to. I mean, I was always closer to my father; it just seemed easier, somehow. He always seemed more approachable. I don't think it was just the shared synaesthesia, either. I wasn't able to put words to it when I was little, but looking back over my relationship with my parents now, what I see in my mind when I think about my mother is a kind of shieldâtransparent maybe, but solidâbetween her and me. And I don't think I constructed it. Or imagined it.

This distance between us, whatever it is, didn't bother me in any conscious way until Dad died. Then it was just the two of us, her and me, and this thing between us that neither of us had ever acknowledged to the other.

I'm probably making it sound bigger and more impenetrable than it is. My relationship with my mum is not terrible or anything. Or, it wasn't, until she dropped this bomb on me.

I'll need a way to refer to

him

. I guess I could use his name, but that feels like giving him so much more respect than he deserves. It's not just that he's half Welsh, either, though that's bad enough.

Do I need to explain that? Let's see. Wales. A country that fought England for far too long in a vain and misguided attempt to resist a superior form of government. We're talking about the twelfth century, here, but remember that England, unlike America, actually has a history and a very long memory.

Wales. Where separate little fiefdoms fought amongst each other at least as much as they fought against the Crownâfiefdoms led by so-called princes whose homes were practically stone huts compared to the castles and palaces of England and France. Wales, a country where a man could decide to leave his entire fortune (not that it would have amounted to much) to a bastard child instead of his legitimate son if he took a notion. A country where a wife who caught her husband in bed with a consort was within her rights to set the bed afire. While they were in it. All of this strikes me as rather . . . well, barbaric. And I'm not alone. Butâdeep sighâwe're all one now, supposedly. One United Kingdom.

I'll grant you that since King Edward I completed the conquest of Wales, things there have changed for the better, but their culture is still limited to singing and mining and fishing and charging money for tourists to see the sad ruins of Marcher Lord castles, which the local peasantry picked apart stone by stone after the English lords no longer needed to fortify the border.

But I think it's their attitude that bothers me the most. It seems to me that they don't take anything seriously enough. They treat everything as though it's just . . . I don't know, part of life. What I mean is, nothing seems to carry enough weight. Or maybe it's that the weight they give to serious things isn't heavier enough, in my estimation, than the weight they give to the less serious things. No doubt they would call it pragmatic. And in a way, I suppose it is. But let's just say that if my boyfriend Graeme and I decided to go to the town green at Abergavenny one night and have sex right there, they'd be more likely to rope off the area and sell tickets than to arrest us. It's not that they're money-grubbing. I don't think they deserve

that

criticism. It's just that they want to make the most of a situation in a way that doesn't always give it the weight it should have. And, all right, my example isn't a very good one; I chose it mostly for shock value. And it was an excuse to mention my boyfriend. But my point is, they just don't take things seriously enough.

So I'm reluctant to take my mother's new husband seriously. But I guess avoiding his name altogether is not going to work. He wants me to call him by his first name, but I can't bring myself to do that. I address him as Mr. Morgan. When I don't merely call him “him.”

His name is Brian Morgan. BM. (Heh. I think that's how I'll refer to him.) And he has a daughter I've never met. Her nameâI hope you're sitting downâis Persephone. I mean, really.

Persephone?

Not sure whether I'm more tempted to call her Percy, which is a favourite name for small dogs in England, or Phony. Evidently they do call her Percy, only with a different spelling: Persie. I think she's nine. Or maybe eleven. BM showed me her picture. Very proud, he was. Don't know why. She looks odd. Dark hair like his, below shoulder length, but even though it's a posed photograph, she's not smiling, and she's not quite looking at the camera. She almost looks like there's no one home, if you know what I mean. And I'll be unable to avoid her if (notice the subjunctive) I end up moving over there.

Mum met BM last January, only seven months ago. How's that for a whirlwind courtship? She was leaving one of her museum committee meetings on a cold and rainy afternoon, typical for London in January, the raw air making it feel colder than it actually was. Mum is nothing if not dignified, and hailing a cab is one of her least favourite things to do, so she has an account with London Black Cabs, and they give her priority when she calls them. The committee meeting was at the Tate Modern, not in the most accessible area of the city, and she had a car scheduled to pick her up. The taxi was late because of the weather and the afternoon traffic, so she was trying to stay out of the rain whilst she waited. There were two men waiting as well, men she didn't know.

A London Black Cab pulled up with a sign saying

F

ITZROY-

H

UNT

,

our last name, displayed in the passenger rear-door window, and according to the story that Mum and BM (who was one of the two men) tell, she popped her brolly, said, “At last!” and headed towards it.

The other man dashed ahead of her and opened the door, and at first she thought he was being a true gentleman and opening it for her. But no, he threw a satchel into the backseat, got in, and shut the door behind him.

It's unlikely that the driver would ever have driven off; my family's account with the company is long-standing. Still, here was this cad of an interloper in the car, and Mum standing in the rain, staring in disbelief at the taxi from several feet away. The way she tells it, BM went flying past her, yanked the door open, and ordered the man out. A tug-of-war ensued on the door whilst the driver, turned around to face the back, yelled at the cad. Finally BM let go, ran around the car, opened the other passenger door, and took the satchel out. With the illicit passenger shouting at him, BM stood in front of the taxi, unfastened some of the satchel's pockets, and was starting to dump things onto the rainy pavement when the fellow gave up and got out. By now the driver was also out of the car, so the cad must have felt outnumbered. He collected his belongings and fled.

BM, dripping wet, held the door open gallantly (per Mum) as she climbed in. She offered to drop him off wherever he needed to go. And on the way to his hotel, they arranged to have dinner the following night.

The rest is history. I'll just give you the outline. He's a bit of a genealogy buff, and he'd indulged in a trip to Wales to research his lineage; his paternal grandparents had immigrated to the US when his father was five. He had included a few days in London before his return home, and he loves modern art, so he went to the Tate Modern on his first day in the city.

I didn't meet him on that trip. Mum told me about the incident with the taxi, and I knew she had met him for dinner, but I didn't know for a long time about the late-night phone calls and the letters and the e-mails and so on and so on. He came back to London once or twice over the next four months, and there was even one trip Mum took to Boston, and I did begin to worry. But I never believed it would come to this.

It was 1 June, I remember specifically, when the full extent of my mother's betrayal was made known to me. She sat me down, showed me photographs of Persie and of BM's house in Boston, which she assures me has a piano even better than ours, and informed me (she probably thought she was much gentler than that, but it could never have been gentle enough) that they would be married in two weeks, and that she and I would move there in late August.

I was supposed to go to the wedding. It wasn't a church affair, just a short ceremony at the British Humanist Association. But I locked myself in my room and refused to come out. Childish, perhaps, but necessary. Not only did the whole thing seem outrageously precipitous, and not only was she forsaking my father's last name for this man's, but also it meant forcing me to cut my own life completely off and relocate to a small, provincial city I don't know and don't want to know.

Oh, my God, we had so many conversations about this. Did I say conversations? Arguments. Battles, more like. I remember one in particular.

Mum seemed to think she could spin things. “I do understand that this seems like the end of the world to you. But it's not. It's the beginning of a new one.”

“I have one word for you, Mother. Oxford.”

“Oh, Simon, you don't have any worries there. You know that you're brilliant, your school career has been outstanding, and my father was at Magdalen College, so even though he's deceased you have a connection.”

“What if I don't want to be at Magdalen?”

“That's fine. Your application will be reviewed by other colleges as well, and any one or any five of them might offer you a place.” She shook her head. “Simon, you will have the world at your feet.”

“All I want is London and Oxford. To hell with the rest of the world.”

Her tone told me she was beginning to get annoyed. “Aren't you at all intrigued by the adventure this represents? The opportunity ? America, Simon. Think of it.”

“My life is here! My school, my friends . . .”

Mum's face took on an odd expression. “Simon, how many times have you told me you don't have any real friends? Certainly you're not close to anyone

I

know about.”

I couldn't really argue that point. I'm not a friendly person, and although I don't really have enemies, I'm not exactly chummy with anyone, either. I once actually overheard some twit at school refer to me as a “nobby no-mates.” Most of my socialising, such as it's been, has been with adults. My parents' friends. I lose patience with people my age; they seem so childish. But I came closeâso closeâto saying something to Mum about Graeme.

Instead, I said, “What about music? You know I've been studying with Dr. Ingerman for ten years! If you interrupt that now, I'll never know how far I could have gone.”

“With piano? Simon, dear, you're very talented. But you know quite well you don't have what it takes to play professionally, to become a concert pianist. We'll find you an excellent teacher in Boston; don't worry about that. You should continue; you're very good. But it doesn't have to be here.”

I didn't want to admit that she was right, or that I didn't even

want

to be a concert pianist, but neither did I want to give that point up so quickly. In trying to come up with a stronger argument, I must have hesitated too long, and she jumped back into the university topic.

“You know, you could consider taking a gap year before starting at university, and spend it studying whatever you want in Boston or New York. Simon, don't underestimate what these opportunities could add to your scholastic résumé, wherever you end up studying.”

Before I could come up with a way to find fault with that argument, Mum threw another stone at my defences. “You should also keep in mind that once you're in the US, you might even want to consider universities there. Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Brownâor you could consider schools in California. Your whole world will open up, Simon. And Oxford is still here.”

“I told you! I don't want the whole world! I want only my parts of it!

My

parts, Mother! Not yours!” This seemed like the only argument I had: just my stubborn hold on the land of my birth, and that hard line, as wide as an ocean, between what she wanted and what I wouldn't let go of. I turned my back on her and headed upstairs towards my room.

Behind me, Mum said, “Don't forget to make sure your room is presentable. There's another showing this afternoon.”

I slammed my door. Adding insult to injury, total strangers had begun tramping through the house, criticising and judging, any one of them potentially purchasing my home and yanking it out from under me, and for this treatment I had to keep making my room “presentable.”

Â

If everything I've told you isn't enough to convince you how terrible this move is, let me remind you: My boyfriend is here in London.

Graeme Godfrey. Gorgeous Graeme. That's what I call him, and to be equally alliterative, and equally admiring, he calls me Sexy Simon. Reddish fuchsia (him), blood red (me). The two together are a rich, heady combination, magnificently exciting when swirled together like marbled paper.

Or like the red in my bathwater.

In that second story line, I picture Graeme visiting me in hospital. He comes in whilst I'm asleep, and I wake up to see him in a chair beside my bed, his blond curls all I can see of his head as he buries his face in the sheets and weeps quietly. I reach out a hand heavy with bandages and stroke those curls, and he sits up quickly.

“Simon! Oh my God, how could you do this? How could you almost leave me like this?”

My head falls back onto the pillow. My voice weary with the weight of the world, I reply, “I have to leave you one way or another. I just wanted to choose the method myself.”

He kisses the ends of my fingers and then stands so he can kiss my mouth.

And I vow that kiss will stay with me always, whatever “always” turns out to be. After I get home, every time I see him, he takes me greedily, like he's afraid every time together will be our last.

And even though that hospital scene didn't really happen, I'm keenly aware that every time I see him will be closer and closer to being our last.