Eight Little Piggies (28 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

This crushing and tragic asymmetry of kindness and violence is infinitely magnified when we consider the causes of history in the large. One fire in the library of Alexandria can wipe out the accumulated wisdom of antiquity. One supposed insult, one crazed act of assassination, can undo decades of patient diplomacy, cultural exchanges, peace corps, pen pals—small acts of kindness involving millions of citizens—and bring two nations to a war that no one wants, but that kills millions and irrevocably changes the paths of history.

Yes, I fully admit that the dark side of human possibility makes most of our history. But this tragic fact does not imply that behavioral traits of the dark side define the essence of human nature. On the contrary, I would argue, by analogy to the ordinary versus the history-making in evolution, that the reality of human interactions at almost any moment of our daily lives runs contrary, and must in any stable society, to the rare and disruptive events that construct history. If you want to understand human nature, defined as our usual propensities in ordinary situations, then find out what traits make history and identify human nature with the opposite sources of stability—the predictable behaviors of nonaggression that prevail for 99.9 percent of our lives. The real tragedy of human existence is not that we are nasty by nature, but that a cruel structural asymmetry grants to rare events of meanness such power to shape our history.

An obvious argument against my thesis holds that I have confused a social possibility of basically democratic societies with a more general human propensity. This alternative view might grant my claims that stability must rule at nearly all moments and that much rare events make history. But perhaps this stability reflects the behaviors of geniality only in relatively free and democratic societies. Perhaps the stability of most cultures has been achieved by the same “dark” forces that make history when they break out of balance—fear, aggression, terror, and domination of rich over poor, men over women, adults over children, and armed over defenseless. I allow that dark forces have often kept balances, but still strongly assert that we fail to count the ten thousand ordinary acts of nonaggression that overwhelm each overt show of strength even in societies structured by domination and even if nonaggression prevails only because people know their places and do not usually challenge the sources of order. To base daily stability on anything other than our natural geniality requires a perverted social structure explicitly dedicated to breaking the human soul—the Auschwitz model, if you will. I am not, by the way, asserting that humans are either genial or aggressive by inborn biological necessity. Obviously, both kindness and violence lie within the bounds of our nature because we perpetuate both, in spades. I only advance a structural claim that social stability rules nearly all the time and must be based on an overwhelmingly predominant (but tragically ignored) frequency of genial acts, and that geniality is therefore our usual and preferred response nearly all the time.

Please don’t read this essay as a bloated effort in the soft tradition of, dare I say it, liberal academic apologies for human harshness, or wishy-washy, far-fetched attempts to make humans look good in a world of woe. This is not an essay about optimism; it is an essay about tragedy. If I felt that humans were nasty by nature, I would just say, the hell with it. We get what we deserve, or what evolution left us as a legacy. But the center of human nature is rooted in ten thousand ordinary acts of kindness that define our days. What can be more tragic than the structural paradox that this Everest of geniality stands upside down on its pointed summit and can be toppled so easily by rare events contrary to our everyday nature—and that these rare events make our history. In some deep sense, we do not get what we deserve.

The solution to our woes lies not in overcoming our “nature” but in fracturing the “great asymmetry” and allowing our ordinary propensities to direct our lives. But how can we put the commonplace into the driver’s seat of history?

GOD MUST HAVE

created mistakes for their wonderful value in illuminating proper pathways. In all of evolutionary biology, I find no error more starkly instructive, or more frequently repeated, than a line of stunning misreason about apes and humans. I have been confronted by this argument in a dozen guises, from the taunts of fundamentalists to the plaints of the honorably puzzled. Consider this excerpt from a letter of April 1981: “If evolution is true, and we did come from apes, then why are there still apes living. It seems if we evolved from them they should not be here.”

If we evolved from apes, why are apes still around? I label this error instructive because its correction is so transforming: If you accept a false notion of evolution, the statement is a deep puzzle; once you reject this fallacy, the statement is evident nonsense (in the literal sense of unintelligible, not the pejorative sense of foolish).

The argument is nonsense because its unstated premise is false. If ancestors are groups of creatures that are bodily transformed, each and every one, into descendants, then human existence would preclude the survival of apes. But, plainly, we mean no such thing in designating groups as ancestors—lest no reptiles remain because birds and mammals evolved or no fishes survive because amphibians once crawled out upon the land.

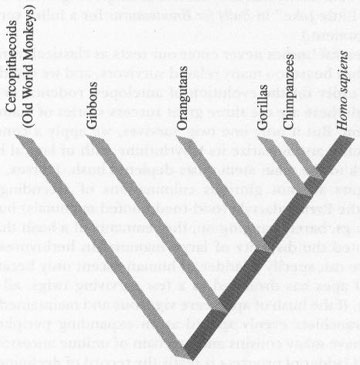

Ladders and bushes, the wrong and right metaphors respectively for the topology of evolution, resolve the persistent non-puzzle of why representatives of ancestral groups (apes, for example) can survive alongside their descendants (humans, for example). Since evolution is a copiously branching bush, the emergence of humans from apes only means that one branch within the bush of apes split off and eventually produced a twig called

Homo sapiens

, while other branches of the same bush evolved along their own dichotomizing pathways to yield the other descendants that share most recent common ancestry with us—gibbons, orangutans, chimps, and gorillas, collectively called apes. (These modern apes are, by genealogy, no closer than we are to the common ancestor that initiated the ape-monkey split more than 20 million years ago, but human hubris demands separation—so our vernacular saddles all modern twigs but us with the ancestral name ape. The figure and its caption should make this clear.)

A Few Branches on the Bush of Apes and

Old World Monkeys

The genealogical sequence of branching in the evolution of apes and humans.

The proper metaphor of the bush also helps us to understand why the search for a “missing link” between advanced ape and incipient human—that musty but persistent hope and chimera of popular writing—is so meaningless. A continuous chain may lack a crucial connection, but a branching bush bears no single link at a crucial threshold between no and yes. Rather, each branching point successively restricts the range of closest relatives—the ancestors of all apes separate from monkeys, then gibbon lineages from ancestors of other great apes and humans, then forebears of the orangutan from the chimp-gorilla-human complex, finally precursors of chimps from the ancestors of humans. No branch point can have special status as

the

missing link—and all represent lateral relationships of diversification, not vertical sequences of transformation.

An even more powerful argument on behalf of the bush arises from the reanalysis of classical ladders in our textbooks, particularly the evolution of modern horses from little eohippus and the “ascent of man” from “the apes.” A precious irony—life’s little joke—pervades these warhorses of the ladder: The “best” examples must be based upon highly

unsuccessful

lineages, bushes so pruned of diversity that they survive as single twigs. (See my essay “Life’s Little Joke” in

Bully for Brontosaurus

for a fuller version of this argument.)

Successful bushes never enter our texts as classical trends, because they boast too many related survivors, and we can draw no rising ladder for the evolution of antelopes, rodents, or bats—although these are the three great success stories of mammalian evolution. But if only one twig survives, we apply a conceptual steamroller and linearize its labyrinthine path of lateral branching back to the main stem of its depleted bush. Horses, rhinos, and tapirs are not glorious culminations of ascending series within the Perissodactyla (odd-toed hoofed mammals) but three little twigs, barely hanging on, the remnants of a bush that once dominated the diversity of large mammalian herbivores. Similarly, we can specify a ladder of human ascent only because the bush of apes has dwindled to a few surviving twigs, all clearly distinct. If the bush of apes were vigorous and maintained a hundred branchlets evenly spaced at an expanding periphery, we would have many cousins and no chain of unique ancestors. Our vaunted ladder of progress is really the record of declining diversity in an unsuccessful lineage that then happened upon a quirky invention called consciousness.

This argument against human arrogance can be grasped well enough as an abstraction but becomes impressive only with its primary documentation—the record of vigorous diversity among apes in former times of greater success. The theme of previous vigor has recently received a boost from a new discovery—one that I had the great good fortune to witness last year.

The cercopithecoid, or Old World, monkeys are the closest relatives of the ape-human bush. Robert Jastrow, in his recent, popular book,

The Enchanted Loom: Mind in the Universe

, contrasts the evolutionary fate of these two sister groups:

The monkey did not change very much from the time of his appearance, 30 million years ago, to the present day. His story was complete. But the evolution of the ape continued. He grew large and heavy, and descended from the trees.

This statement, so preciously wrong, so perfectly arse-backward, shows just how far astray the metaphor of the ladder can lead. There is no such creature, not even as a useful abstraction, as

the

monkey or

the

ape. Evolution’s themes are diversity and branching. Most apes (gibbons and orangutans, and chimps and gorillas a good part of the time) are still living in trees. Old World monkeys have not stagnated; they represent the greatest success story among primates, a bush in vigorous radiation and including among its varied products baboons, colobins, rhesus and proboscis monkeys.

In fact, precisely opposite to Jastrow’s claim, apes have been continuously losing and cercopithecoids gaining by the proper criteria of diversity and expansion of the bush. Let us go back to the early Miocene of Africa, some 20 million years ago, soon after the ape-monkey split, and trace the fate of these two sister groups. First of all, we would not find these Miocene ancestors as different from each other as their descendants are today—limbs of a bush usually diverge. Early Miocene apes were quite monkey-like in their modes of life. Compared with monkey forebears, early apes tended to be larger, more tree bound, more narrowly tied to fruit eating, and less likely to cope with a strongly seasonal or open environment.

Second—and the crucial point for this essay—apes were more common in two important senses during the early Miocene: more common than cercopithecoid monkeys at this early stage in their mutual evolution, and absolutely more diverse (just in Africa) than apes are today (all over the world). Taxonomic estimates vary, and this essay cannot treat such a highly technical and contentious literature, but early Miocene African apes have been placed in some three to five genera and perhaps twice as many species.

The next snapshot of time, the African middle Miocene, already records fewer species, although apes now appear for the first time in the fossil records of Europe and Asia. Old World monkeys meanwhile begin an acceleration extending right to our own time. Apes continue to decline and hang on in restricted habitats—yielding isolated groups of gibbons and orangutans in Asia, and chimps, gorillas, and the descendants of a small African group called australopithecines. If the resident zoologist of Galaxy X had visited the earth 5 million years ago while making his inventory of inhabited planets in the universe, he would surely have corrected his earlier report that apes showed more promise than Old World monkeys and noted that monkeys had overcome an original disadvantage to gain domination among primates. (He will confirm this statement after his visit next year—but also add a footnote that one species from the ape bush has enjoyed an unusual and unexpected flowering, thus demanding closer monitoring.)

We do not know why apes have declined and monkeys prevailed. We have no evidence for “superiority” of monkeys; that is, for direct struggles of Darwinian competition between apes and monkeys in the same habitat, with ape extinction and cercopithecoid prevalence as a result. Perhaps a greater flexibility in diet and environmental tolerance allowed monkeys to gain the edge, without any direct competition, in a world of changing climate and fewer stable habitats of trees and fruit. According to this interpretation, those few apes that could adapt to a more open, ground-living existence, had to develop some decidedly odd features, not in any way “prefigured” by their initial design—the knuckle walking of chimps and gorillas, and the upright gait of australopithecines and you know who.

This striking reversal of Jastrow’s homily, and of all standard biases of the ladder, rests most forcefully upon the comparison of initial Miocene success with later restriction of the bush of apes. But how great was this first flowering, and how severe, therefore, the later pruning? Unfortunately, this most crucial of all empirical questions encounters the cardinal problem of our woefully imperfect fossil record. We know the extent of later pruning; it is not likely that any living species of ape remains undiscovered on our well-explored earth. But what was the true diversity of early Miocene apes? Did they live only in Africa? What fraction of the African fauna has been preserved? What have we collected and identified of the material that has been preserved?

If our current collections contain most of what actually lived, then the pruning has been notable but modest. But suppose that we have only 10 percent or even only half the true diversity, then the story of decline and restriction among apes is far more pronounced. How can we know how much we have?

One rough indication—about the best we can do at this early stage of knowledge about Miocene primates in Africa—comes from the composition of new collections. Suppose that every time we find new early Miocene apes in Africa, they belong to species already in our collections. After several repetitions (particularly if our collections span a good range of geographies and environments), we might conclude that we have probably sampled a substantial amount of the true bush. But suppose that new sites yield new species most of the time—and that we can mark no real decline in the number of novelties. Then we might conclude that we have sampled only a small part of a much more copious bush—and that the story of decline and shortfall in the empire of apes has been more profound than we realized. Quite an effective antidote to the bias of the ladder and its attendant invitation to human arrogance!

In other words, we are seeking, as my colleague David Pilbeam, our leading student of fossil apes, said to me, “an asymptote” in the discovery of new apes. An asymptote is a limiting value approached by one variable of a curve as the other variable (often time or number of trials) increases towards infinity. When further collecting of fossils only yields more specimens of the same species, we have probably reached the asymptote in recoverable kinds of apes. We also reach asymptotes fairly quickly in training cats or cajoling children and should learn to recognize both the subtle point of diminishing returns and the actual asymptote not much further down the line.

An exciting discovery about the history of Miocene apes has recently furnished our best evidence that we have not yet come near the asymptote of the early bush of apes. This discovery provides the strongest possible evidence for an even greater intensity of life’s little joke in our own evolution. The bush was bushier, the later decline in diversity more profound. We do not yet know the true extent of the initial success of apery.

In January 1986, I spent a week with Richard Leakey at his field camp on early Miocene sediments near the western shore of Lake Turkana in Africa’s Great Rift Valley. Little vegetation obscures the geology of this arid region, and naked sediments stretch for miles, their eroding fossils littering the surface.

The data on genetic differences between chimps and humans suggest that our twig on the bush of apes last shared a common ancestor with chimps some 5 to 8 million years ago; in other words, the human lineage has been entirely on its own only for this short stretch of geological time. The oldest human fossils are less than 4 million years old, and we do not know which branch on the copious bush of apes budded off the twig that led to our lineage. (In fact, except for the link of Asian

Sivapithecus

to the modern orangutan, we cannot trace any fossil ape to any living species. Paleontologists have abandoned the once popular notion that

Ramapithecus

might be a source of human ancestry.) Thus, sediments between 4 and 10 million years in age are potential guardians of the Holy Grail of human evolution—the period when our lineage began its separate end run to later domination and a time for which no fossil evidence exists at all.