Elizabeth the Queen (34 page)

Read Elizabeth the Queen Online

Authors: Sally Bedell Smith

Annenberg had reported to Richard Nixon that his credentials presentation had been “infinitely rewarding and impressive.” But when

Royal Family

aired on the BBC on June 21, 1969, the American ambassador’s “elements of refurbishment” remark produced howls of laughter and widespread ridicule in Britain. Newspapers challenged readers to produce even more egregious phrases;

The Sunday Times

called Annenberg the “flustered envoy”; and one magazine said he had the “verbal felicity of W. C. Fields.” What the press did not know was that the sixty-one-year-old ambassador, like the Queen’s own father, had suffered from a lifetime of stuttering. Through speech therapy, he had learned the somewhat paradoxical strategy of framing complex sentences with ornate words to prevent verbal stumbling. Annenberg was so mortified by the outcry that he told Secretary of State William Rogers he would resign if Nixon thought he couldn’t be effective in his job. Nixon reassured his ambassador that he should stay in place.

“When we reviewed the film before it was finished, the great refurbishment thing was rather laughable and we debated whether to include it,” Martin Charteris later admitted. “We allowed it to remain, but we should not have. As a result, I think the royal family felt a certain sense of guilt about Walter because they allowed a joke to be made about him. In fact, he was honorable and straightforward.”

For all its appearance of spontaneity, the film was in fact a tightly controlled rebranding of the royal family as accessible and folksy, engaging in activities ordinary people could relate to. Most critics applauded the film’s humanizing effect. Cecil Beaton, who had observed the Queen closely for more than two decades, thought she “came through as a great character, quite severe, very self-assured, a bit bossy, serious, frowning a bit (and very lined). Her sentences are halting. She hesitates mid-way, you think she has dried up … but she goes on doggedly. She came out on top as the nice person she is.”

There was some inevitable mockery of the family’s old-fashioned traditions and stodgy costumes. One wag called the film “Corgi and Beth,” and

Private Eye

came up with working-class nicknames: the Queen was Brenda, Prince Philip was Keith, Princess Margaret was Yvonne, and Prince Charles was Brian.

Some worried about the consequences of violating the precept set out in the nineteenth century by economist and constitutional expert Walter Bagehot that a sovereign should maintain a measure of mystery: “We must not let in daylight upon magic.” Milton Shulman, the television critic for the

Evening Standard

, questioned the authenticity of the Queen and her family behaving “like a middle-class family in Surbiton or Croydon,” and wondered about the precedent of using television “to act as an image-making apparatus for the monarchy,” noting that “every institution that has so far attempted to use TV to popularize or aggrandize itself has been trivialized by it.” Even the BBC’s David Attenborough, one of the producers of

Royal Family

, declared that the film could kill the monarchy, an institution that “depends on mystique and the tribal chief in his hut. If any member of the tribe ever sees inside the hut, then the whole system of the tribal chiefdom is damaged and the tribe eventually disintegrates.”

Neither the Queen nor the Palace hierarchy expressed second thoughts, although she never again permitted that kind of intimate entrée. Princess Anne later said that the film had been a “rotten idea” that she “never liked.… The attention that had been brought on one since one was a child, you just didn’t want any more. The last thing you needed was great access.” But the reaction of the public was overwhelmingly positive.

Royal Family

was repeated five times and was seen by forty million viewers in the United Kingdom and an estimated 400 million in 130 countries. Viewers were captivated by the informality of the Queen and her family and surprised to hear her conversational voice as well as her infectious laugh.

T

HE GLOW OF

good feeling created by the film carried over to the investiture of Prince Charles on July 1, which was televised from the grassy courtyard of ancient Caernarvon Castle in Wales. Only one previous Prince of Wales, Charles’s great-uncle, the Duke of Windsor, had been officially inducted in the role, in a ceremony at the castle in 1911. To help create a stronger bond with Wales, overcome historic resentments dating from the country’s conquest by English kings in the thirteenth century, and restrain incipient nationalistic feelings, his mother had arranged for Charles to leave Cambridge the previous spring for eight weeks at University College, Aberystwyth. There he picked up some rudimentary Welsh, and was tutored in the history of the country’s nationalism—valuable lessons, he said afterward, that helped him understand that the “language and culture” were “very unique and special to Wales” and “well worth preserving.”

The actual investiture ceremony was a twentieth-century invention evoking medieval traditions, orchestrated by the Duke of Norfolk on a contemporary stage set created by Welshman Lord Snowdon, who was a designer as well as a photographer. With TV cameras in mind, Snowdon designed a low round slate dais underneath a minimalist Plexiglas canopy supported by steel poles resembling pikestaffs. On the dais were three austere thrones of slate with scarlet cushions. Snowdon intended to project a “grand and simple” image of a modern monarchy. “I didn’t want red carpets,” Snowdon said. “I wanted him to walk across simple green grass.”

The Queen was surprisingly on edge while she prepared for the procession into the courtyard. With noticeable agitation, she wondered aloud if the text of what she had to say would be on her seat. Philip snapped that he had no idea, “that it was her show not his.” After exchanging more cross words, they moved off, their faces suitably arranged.

As she waited on the dais for the arrival of her son, Elizabeth II tucked her white handbag under one arm and held a furled umbrella in the other—an unnecessary precaution, since there was only a brief light drizzle. With four thousand invited guests looking on, Charles emerged from the Chamberlain Tower in his dark blue dress uniform of Colonel-in-Chief of the Royal Regiment of Wales, decorated with his gleaming Garter collar.

The climax of the ceremony came when he kneeled before his mother, who invested him with the insignia of his office in a solemn ritual punctuated with his periodic shy smiles. She first presented him with a sword inscribed with his motto “Ich Dien” (I serve), hanging it gently around his neck before adjusting the strap attached to its scabbard. She then crowned him with a coronet of 24-karat Welsh gold set sparingly with diamonds and emeralds over a purple velvet cap trimmed in ermine. Unlike other royal crowns, Charles’s was strikingly stylized, with a single arch topped by an engraved orb, and crosses like stickpins interspersed with plainly wrought versions of the three-feathers emblem of the Prince of Wales.

As Elizabeth II put the coronet on his head, it settled just above his eyes, and he helped her by nudging it into place with his fingertips. She slipped onto his left hand a cabochon amethyst ring, symbolizing his unity with Wales, gave him his golden rod (for temporal rule), and draped a purple silk mantle with wide ermine collar on his shoulders, smoothing it into place in a practiced maternal gesture before fastening the gold clasp. After he had paid her homage, she raised him up and they exchanged the kiss of fealty on their left cheeks, signifying her pledge to protect the prince in his duties.

“By far the most moving and meaningful moment,” he later wrote, “came when I put my hands between Mummy’s and swore to be her liege man of life and limb and to live and die against all manner of folks.” Those were the precise words his father had used during the Queen’s coronation, and to Charles they were “magnificent, medieval, appropriate.” The Queen looked suitably somber as well, although later that month, over lunch at Royal Lodge, Noel Coward told her that he had found the investiture moving. “She gaily shattered my sentimental illusions,” Coward recorded, “by saying that they were both struggling not to giggle because at the dress rehearsal the crown was too big and extinguished him like a candle-snuffer!”

An estimated worldwide television audience of 500 million had watched the heir to the throne’s official coming of age. For Charles, the investiture marked the start of his apprenticeship as king-in-waiting, the length of which he could never have imagined.

He used to say to Elizabeth II,

“Your job is to spread a carpet

of happiness.”

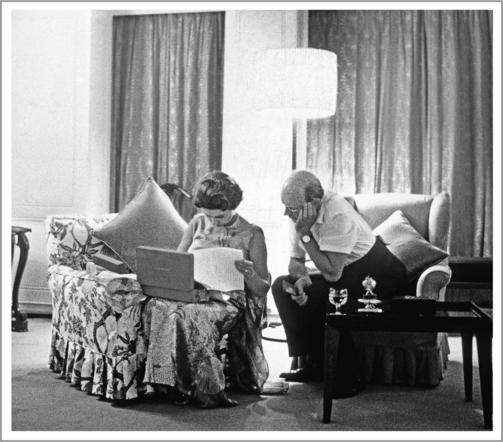

The Queen reviewing papers with her long-serving private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, late at night aboard the royal yacht

Britannia

, March 1972.

Lichfield/Getty Images

TEN

Ring of Silence

Ring of Silence

P

IETRO

A

NNIGONI RETURNED TO

B

UCKINGHAM

P

ALACE IN THE SPRING

and fall of 1969 to paint the Queen’s portrait for the second time. After an interval of fifteen years, Annigoni could detect changes that eluded those who saw the forty-three-year-old Queen every day. “Everything about her seemed smaller,” he observed, “in some ways frailer and in some ways harder. As she posed her facial expression was mercurial—smiling, thoughtful, determined, uncertain, relaxed, taut, in rapid succession.… At every sitting the Queen chatted to me in the most natural way, and her disarming frankness never failed to surprise and fascinate me.”

The diminutive artist forthrightly outlined to the Queen his vision for the portrait: “I see Your Majesty as being condemned to solitude because of your position,” he said. “As a wife and mother you are entirely different, but I see you really alone as a monarch and I want to represent you that way. If I succeed, the woman, the Queen and, for that matter, the solitude will emerge.” She nodded, examined the study he had painted during eight sittings and said, “One doesn’t know one’s self. After all, we have a biased view when we see ourselves in a mirror and, what’s more, the image is always in reverse.” She assented to his plan to portray her looking “thoughtful and severe, profoundly human,” queenly yet unembellished. “I feel that the inspiration is there,” she said.

They resumed their sittings at the end of October after she returned from Balmoral. In the interval, the world had been riveted by the landing of the first men on the moon. The Queen had become fascinated by these twentieth-century explorers after David Bruce brought

Apollo 8

astronaut Frank Borman—commander of the first crew to orbit the moon—his wife, and two young sons to Buckingham Palace the previous February.

When Neil Armstrong walked on the moon on July 20, he carried a microfilm message from the Queen to leave behind. She also sent her congratulations to the crew of

Apollo 11

“and to the American people on this historic occasion.” She said the fortitude of astronauts Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins filled her with admiration, and that their exploits “add a new dimension to man’s knowledge of the universe.” The three American heroes came to London the following October as part of a world tour, and their first stop was Buckingham Palace, where they were greeted by Elizabeth II and her family. Somewhat sweetly, the men even bowed to little Andrew and Edward when they shook hands. The astronauts, all of whom were suffering from laryngitis and colds, remarked on how well informed the Queen was about their space voyage.

Elizabeth II now had a rooting interest in the

Apollo 12

crew when they blasted into space on November 14. She confessed to Annigoni that she had been waking up early to watch the television coverage of the second moon landing. During two of her sittings, she spent considerable time describing the mission’s progress in detail, although she concurred with the artist that while “it filled us with wonder and admiration, it did not move us emotionally.”