Emotional Design (5 page)

Authors: Donald A. Norman

When under high anxietyâhigh negative affectâpeople focus upon escape. When they reach the door, they push. And when this fails, the natural response is to push even harder. Countless people have died as a result. Now, fire laws require what is called “panic hardware.” The doors of auditoriums have to open outward, and they must open whenever pressure is applied.

Similarly, designers of exit stairways have to block any direct path from the ground floor to those floors below it. Otherwise, people

using a stairway to escape a fire are likely to miss the ground floor and continue all the way into the basementâand some buildings have several levels of basementsâto end up trapped.

The Prepared Brainusing a stairway to escape a fire are likely to miss the ground floor and continue all the way into the basementâand some buildings have several levels of basementsâto end up trapped.

Although the visceral level is the simplest and most primitive part of the brain, it is sensitive to a very wide range of conditions. These are genetically determined, with the conditions evolving slowly over the time course of evolution. They all share one property, however: the condition can be recognized simply by the sensory information. The visceral level is incapable of reasoning, of comparing a situation with past history. It works by what cognitive scientists call “pattern matching.” What are people genetically programmed for? Those situations and objects that, throughout evolutionary history, offer food, warmth, or protection give rise to positive affect. These conditions include:

warm, comfortably lit places,

temperate climate,

sweet tastes and smells,

bright, highly saturated hues,

“soothing” sounds and simple melodies and rhythms,

harmonious music and sounds,

caresses,

smiling faces,

rhythmic beats,

“attractive” people,

symmetrical objects,

rounded, smooth objects,

“sensuous” feelings, sounds, and shapes.

temperate climate,

sweet tastes and smells,

bright, highly saturated hues,

“soothing” sounds and simple melodies and rhythms,

harmonious music and sounds,

caresses,

smiling faces,

rhythmic beats,

“attractive” people,

symmetrical objects,

rounded, smooth objects,

“sensuous” feelings, sounds, and shapes.

Similarly, here are some of the conditions that appear to produce automatic negative affect:

heights,

sudden, unexpected loud sounds or bright lights,

“looming” objects (objects that appear to be about to hit the

observer),

extreme hot or cold,

darkness,

extremely bright lights or loud sounds,

empty, flat terrain (deserts),

crowded dense terrain (jungles or forests),

crowds of people,

rotting smells, decaying foods

bitter tastes,

sharp objects,

harsh, abrupt sounds,

grating and discordant sounds,

misshapen human bodies,

snakes and spiders,

human feces (and its smell),

other people's body fluids,

vomit.

sudden, unexpected loud sounds or bright lights,

“looming” objects (objects that appear to be about to hit the

observer),

extreme hot or cold,

darkness,

extremely bright lights or loud sounds,

empty, flat terrain (deserts),

crowded dense terrain (jungles or forests),

crowds of people,

rotting smells, decaying foods

bitter tastes,

sharp objects,

harsh, abrupt sounds,

grating and discordant sounds,

misshapen human bodies,

snakes and spiders,

human feces (and its smell),

other people's body fluids,

vomit.

These lists are my best guess about what might be automatically programmed into the human system. Some of the items are still under dispute; others will probably have to be added. Some are politically incorrect in that they appear to produce value judgments on dimensions society has deemed to be irrelevant. The advantage human beings have over other animals is our powerful reflective level that enables us to overcome the dictates of the visceral, pure biological level. We can overcome our biological heritage.

Note that some biological mechanisms are only predispositions rather than full-fledged systems. Thus, although we are predisposed to be afraid of snakes and spiders, the actual fear is not present in all people: it needs to be triggered through experience. Although human language comes from the behavioral and reflective levels, it provides a

good example of how biological predispositions mix with experience. The human brain comes ready for language: the architecture of the brain, the way the different components are structured and interact, constrains the very nature of language. Children do not come into the world with language, but they do come predisposed and ready. That is the biological part. But the particular language you learn, and the accent with which you speak it, are determined through experience. Because the brain is prepared to learn language, everyone does so unless they have severe neurological or physical deficits. Moreover, the learning is automatic: we may have to go to school to learn to read and write, but not to listen and speak. Spoken languageâor signing, for those who are deafâis natural. Although languages differ, they all follow certain universal regularities. But once the first language has been learned, it highly influences later language acquisition. If you have ever tried to learn a second language beyond your teenage years, you know how different it is from learning the first, how much harder, how reflective and conscious it seems compared to the subconscious, relatively effortless experience of learning the first language. Accents are the hardest thing to learn for the older language-learner, so that people who learn a language later in life may be completely fluent in their speech, understanding, and writing, but maintain the accent of their first language.

good example of how biological predispositions mix with experience. The human brain comes ready for language: the architecture of the brain, the way the different components are structured and interact, constrains the very nature of language. Children do not come into the world with language, but they do come predisposed and ready. That is the biological part. But the particular language you learn, and the accent with which you speak it, are determined through experience. Because the brain is prepared to learn language, everyone does so unless they have severe neurological or physical deficits. Moreover, the learning is automatic: we may have to go to school to learn to read and write, but not to listen and speak. Spoken languageâor signing, for those who are deafâis natural. Although languages differ, they all follow certain universal regularities. But once the first language has been learned, it highly influences later language acquisition. If you have ever tried to learn a second language beyond your teenage years, you know how different it is from learning the first, how much harder, how reflective and conscious it seems compared to the subconscious, relatively effortless experience of learning the first language. Accents are the hardest thing to learn for the older language-learner, so that people who learn a language later in life may be completely fluent in their speech, understanding, and writing, but maintain the accent of their first language.

Tinko

and

losse

are two words in the mythical language Elvish, invented by the British philologist J. R. R. Tolkien for his trilogy,

The Lord of the Rings.

Which of the words

“tinko”

and

“losse”

means “metal,” which “snow”? How could you possibly know? The surprise is that when forced to guess, most people can get the choices right, even if they have never read the books, never experienced the words.

Tinko

has two hard, “plosive” soundsâthe “t” and the “k.”

Losse

has soft, liquid sounds, starting with the “l” and continuing through the vowels and the sibilant “ss.” Note the similar pattern in the English words where the hard “t” in “metal” contrasts with the soft sounds of “snow.” Yes, in Elvish,

tinko

is metal and

losse

is snow.

and

losse

are two words in the mythical language Elvish, invented by the British philologist J. R. R. Tolkien for his trilogy,

The Lord of the Rings.

Which of the words

“tinko”

and

“losse”

means “metal,” which “snow”? How could you possibly know? The surprise is that when forced to guess, most people can get the choices right, even if they have never read the books, never experienced the words.

Tinko

has two hard, “plosive” soundsâthe “t” and the “k.”

Losse

has soft, liquid sounds, starting with the “l” and continuing through the vowels and the sibilant “ss.” Note the similar pattern in the English words where the hard “t” in “metal” contrasts with the soft sounds of “snow.” Yes, in Elvish,

tinko

is metal and

losse

is snow.

The Elvish demonstration points out the relationship between the

sounds of a language and the meaning of words. At first glance, this sounds nonsensicalâafter all, words are arbitrary. But more and more evidence piles up linking sounds to particular general meanings. For instance, vowels are warm and soft:

feminine

is the term frequently used. Harsh sounds are, well, harshâjust like the word “harsh” itself and the “sh” sound in particular. Snakes hiss and slither; and note the sibilants, the hissing of the “s” sounds. Plosives, sounds caused when the air is stopped briefly, then releasedâexplosivelyâare hard, metallic; the word “masculine” is often applied to them. The “k” of “mosquito” and the “p” in “happy” are plosive. And, yes, there is evidence that word choices are not arbitrary: a sound symbolism governs the development of a language. This is another instance where artists, poets in this case, have long known the power of sounds to evoke affect and emotions within the readers ofâor, more accurately, listeners toâpoetry.

sounds of a language and the meaning of words. At first glance, this sounds nonsensicalâafter all, words are arbitrary. But more and more evidence piles up linking sounds to particular general meanings. For instance, vowels are warm and soft:

feminine

is the term frequently used. Harsh sounds are, well, harshâjust like the word “harsh” itself and the “sh” sound in particular. Snakes hiss and slither; and note the sibilants, the hissing of the “s” sounds. Plosives, sounds caused when the air is stopped briefly, then releasedâexplosivelyâare hard, metallic; the word “masculine” is often applied to them. The “k” of “mosquito” and the “p” in “happy” are plosive. And, yes, there is evidence that word choices are not arbitrary: a sound symbolism governs the development of a language. This is another instance where artists, poets in this case, have long known the power of sounds to evoke affect and emotions within the readers ofâor, more accurately, listeners toâpoetry.

All these prewired mechanisms are vital to daily life and our interactions with people and things. Accordingly, they are important for design. While designers can use this knowledge of the brain to make designs more effective, there is no simple set of rules. The human mind is incredibly complex, and although all people have basically the same form of body and brain, they also have huge individual differences.

Emotions, moods, traits, and personality are all aspects of the different ways in which people's minds work, especially along the affective, emotional domain. Emotions change behavior over a relatively short term, for they are responsive to the immediate events. Emotions last for relatively short periodsâminutes or hours. Moods are longer lasting, measured perhaps in hours or days. Traits are very long-lasting, years or even a lifetime. And personality is the particular collection of traits of a person that last a lifetime. But all of these are changeable as well. We all have multiple personalities, emphasizing some traits when with families, a different set when with friends. We all change our operating parameters to be appropriate for the situation we are in.

Ever watch a movie with great enjoyment, then watch it a second time and wonder what on earth you saw in it the first time? The same phenomenon occurs in almost all aspects of life, whether in interactions with people, in a sport, a book, or even a walk in the woods. This phenomenon can bedevil the designer who wants to know how to design something that will appeal to everyone: One person's acceptance is another one's rejection. Worse, what is appealing at one moment may not be at another.

The source of this complexity can be found in the three levels of processing. At the visceral level, people are pretty much the same all over the world. Yes, individuals vary, so although almost everyone is born with a fear of heights, this fear is so extreme in some people that they cannot function normallyâthey have acrophobia. Yet others have only mild fear, and they can overcome it sufficiently to do rock climbing, circus acts, or other jobs that have them working high in the air.

The behavioral and reflective levels, however, are very sensitive to experiences, training, and education. Cultural views have huge impact here: what one culture finds appealing, another may not. Indeed, teenage culture seems to dislike things solely because adult culture likes them.

So what is the designer to do? In part, that is the theme of the rest of the book. But the challenges should be thought of as opportunities. Designers will never lack for things to do, for new approaches to explore.

CHAPTER TWO

The Multiple Faces of Emotion and Design

AFTER DINNER, WITH A GREAT FLOURISH, my friend Andrew brought out a lovely leather box. “Open it,” he said, proudly, “and tell me what you think.”

I opened the box. Inside was a gleaming stainless-steel set of old mechanical drawing instruments: dividers, compasses, extension arms for the compasses, an assortment of points, lead holders, and pens that could be fitted onto the dividers and compasses. All that was missing was the T square, the triangles, and the table. And the ink, the black India ink.

“Lovely,” I said. “Those were the good old days, when we drew by hand, not by computer.”

Our eyes misted as we fondled the metal pieces.

“But you know,” I went on, “I hated it. My tools always slipped, the point moved before I could finish the circle, and the India inkâugh, the India inkâit always blotted before I could finish a diagram. Ruined it! I used to curse and scream at it. I once spilled the whole bottle

all over the drawing, my books, and the table. India ink doesn't wash off. I hated it. Hated it!”

all over the drawing, my books, and the table. India ink doesn't wash off. I hated it. Hated it!”

“Yeah,” said Andrew, laughing, “you're right. I forgot how much I hated it. Worst of all was too much ink on the nibs! But the instruments are nice, aren't they?”

“Very nice,” I said, “as long as we don't have to use them.”

Â

Â

THIS STORY shows the several levels of the cognitive and emotional systemâvisceral, behavioral, and reflectiveâat work, fighting among themselves. First, the most basic visceral level responds with pleasure to seeing the well-designed leather case and gleaming stainless-steel instruments and to feeling their comfortable heft. That visceral response is immediate and positive, triggering the reflective system to think back about the past, many decades ago, “the good old days,” when my friend and I actually used those tools. But the more we reflect upon the past, the more we remember the actual negative experiences, and herein lies the conflict with the initial visceral reaction.

We recall how badly we actually performed, how the tools were never completely under control, sometimes causing us to lose hours of work. Now, in each of us, visceral is pitted against reflection. The sight of the classic tools is attractive, but the memory of their use is negative. Because the power of emotion fades with time, the negative affect generated by our memories doesn't overcome the positive affect generated by the sight of the instruments themselves.

This conflict among different levels of emotion is common in design: Real products provide a continual set of conflicts. A person interprets an experience at many levels, but what appeals at one may not at another. A successful design has to excel at all levels. While logic might imply, for example, that it is bad business to scare customers, amusement and theme parks have many customers for rides and haunted houses designed to scare. But the scaring occurs in a safe, reassuring environment.

The design requirements for each level differ widely. The visceral

level is pre-consciousness, pre-thought. This is where appearance matters and first impressions are formed. Visceral design is about the initial impact of a product, about its appearance, touch, and feel.

level is pre-consciousness, pre-thought. This is where appearance matters and first impressions are formed. Visceral design is about the initial impact of a product, about its appearance, touch, and feel.

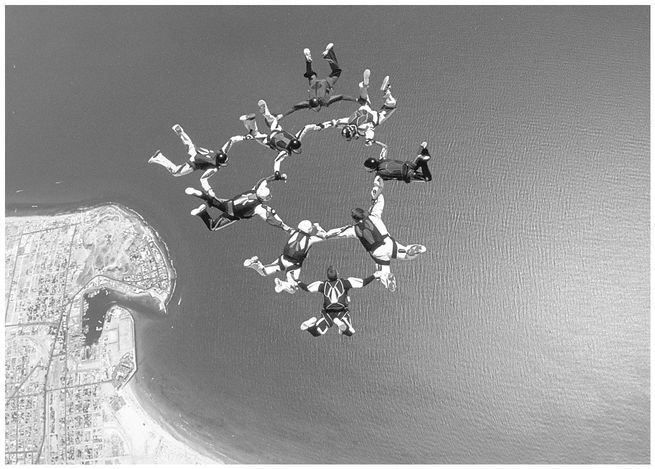

FIGURE 2.1

Sky diving:

An innate fear of heights or a pleasurable experience?

Sky diving:

An innate fear of heights or a pleasurable experience?

(Rocky Point Pictures; courtesy of Terry Schumacher.)

The behavioral level is about use, about experience with a product. But experience itself has many facets: function, performance, and usability. A product's function specifies what activities it supports, what it is meant to doâif the functions are inadequate or of no interest, the product is of little value. Performance is about how well the product does those desired functionsâif the performance is inadequate, the product fails. Usability describes the ease with which the user of the product can understand how it works and how to get it to perform. Confuse or frustrate the person who is using the product and negative emotions result. But if the product does what is needed, if it is fun to use and easy to satisfy goals with it, then the result is warm, positive affect.

Other books

What Einstein Kept Under His Hat: Secrets of Science in the Kitchen by Wolke, Robert L.

Atlantia Series 3: Aggressor by Dean Crawford

Where Two Hearts Meet by Carrie Turansky

Twisted Lies 2 by Sedona Venez

In Another Country by David Constantine

A Heart Decision by Laurie Kellogg

Zendikar: In the Teeth of Akoum by Robert B. Wintermute

Three Little Maids by Patricia Scott

The Curious Case of the Mayo Librarian by Pat Walsh