Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (10 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

In the scale of things the actual fighting had been quite light; the shattering collision of massed galleys had simply not occurred. The Holy League lost perhaps twelve ships, a number dwarfed a few days later when seventy Ottoman ships were destroyed in a storm, but the psychological damage to the Holy League was immense. The Christians had been totally outmaneuvered. Of the Christian losses, most had fallen to the Venetians. Their ships had not been supported by Doria, and the Venetians were furious. They sensed treachery, malice, or cowardice by the Genoese admiral. Either Doria had been less than enthusiastic in the enterprise or he had been outmaneuvered by superior seamanship and had cut and run to limit the damage to his galleys. It seems highly likely that Barbarossa had gained the upper hand; safely tucked into the gulf of Preveza, he could choose the moment to strike when his opponents were at the mercy of the wind, but there were other factors that might have compromised the desire of either man to fight to the death.

What the Venetians did not know was that Charles, having failed to destroy Barbarossa at Tunis, had resorted to underhand methods. In 1537 he entered secret negotiations with the sultan’s admiral to induce him to switch sides, and these talks were still taking place on the very eve of battle. On September 20, 1538, a Spanish messenger from Barbarossa held a meeting with Doria and the viceroy of Sicily. The terms could not be agreed—Barbarossa was said to have demanded the return of Tunis—but the negotiations suggested a certain complicity between the two admirals; both were hired hands whose reputations were at stake; both had reasons to be cautious. They had much more to lose than gain by a rash gamble on the state of the wind. The Spanish knowingly recalled the proverb that one crow does not peck out another’s eyes. For Doria there were other business considerations: many of the galleys were his own property; he was certainly loath to lose them helping the detestable Venetians. It would take less experienced commanders to throw caution to the wind and risk everything in the same stretch of water thirty years later.

It is impossible to determine Barbarossa’s sincerity in these maneuvers. Maybe the downfall of Ibrahim Pasha had illustrated the perils of high office in the sultan’s service, or perhaps Charles had offered Barbarossa the chance to realize his dream of an independent kingdom in the Maghreb. More likely, Barbarossa’s behavior was a way of playing Charles and Doria along, lulling his opponents into doubt and hesitation. Certainly, a French agent in Istanbul by the name of Dr. Romero had no doubts. “I can guarantee that [Barbarossa] is a better Muslim than Mohammed,” he wrote. “The negotiations are a front.”

If at first sight the immediate military consequences of Preveza seemed slight, the political and psychological ones were enormous. Only a unified Christian fleet could match the resources at the disposal of the Ottomans. In 1538 the idea of any coordinated Christian maritime response to the Turks had proved unworkable. The Holy League collapsed: in 1540 the Venetians signed a humiliating peace with the sultan. They paid a hefty ransom and acknowledged the loss of all their possessions taken by Barbarossa. They were virtually reduced to the status of vassals, though no one was using that term. The Venetians, the most experienced mariners in the whole sea, would not launch ships in anger for a quarter of a century, when distrust of the Doria clan would rise again. Preveza opened the door to Ottoman domination of the Mediterranean. All that the Venetians took away from the fight was the performance of their great galleon; they stored for future reference the value of stoutly built floating gun platforms.

CHARLES MADE ONE

further personal attempt to break the strangle-hold of Ottoman power in the western sea. Remembering the triumph of Tunis, he determined on a similar operation against Algiers. In the summer of 1541 Suleiman was in Hungary and Barbarossa was conducting naval operations up the Danube. It was an ideal moment to strike.

There was a streak of risk-taking in the emperor. By 1541 his treasury was under extreme pressure. To cut costs, he decided to descend on Algiers late in the year. It reduced the number of troops he had to pay, as he could be sure no fleet from Istanbul would come to oppose him on the wintering sea. Doria warned him about the gamble, but Charles was resolved to ride his luck.

The outcome was catastrophic. His substantial fleet sailed from Genoa in late September. Among the gentleman adventurers who accompanied the expedition was Hernando Cortez, the conqueror of Mexico, trying his fortune in the Old World. It was October 20 before all the units were gathered at Algiers, but the weather was fair. Only after the army had disembarked and was awaiting its supplies did Charles’s luck run out. On the night of October 23 torrential rain started to fall; the men could not keep their powder dry, and suddenly found themselves at a disadvantage. Barbarossa had appointed an Italian renegade, Hasan, as governor of Algiers in his absence. Hasan acted with courage and determination. Sallying out of the city, he put Charles’s army to flight. Only a small detachment of the Knights of Saint John prevented a total rout. Worse followed. Overnight the wind intensified; one by one the sailing ships riding offshore dragged their creaking anchors and rode onto the beach. As the survivors staggered through the pounding surf in the dark, they were massacred by the local population. Charles was forced to beat a ragged retreat twenty miles down the coast to a point where Doria’s galleys could take him off. There were too few ships to re-embark the bulk of the army. With his galley bucking and heaving dangerously offshore, Charles threw his horses overboard and departed the Barbary Coast with the blasphemous screams of his abandoned army reaching him on the tempestuous wind. He had lost one hundred forty sailing ships, fifteen galleys, eight thousand men, and three hundred Spanish aristocrats. The sea had delivered a total humiliation. There was a glut of slaves in Algiers, so many that 1541 was said to be the year when Christians sold at an onion a head.

Charles viewed this catastrophe with a remarkable levelness of spirit. “We must thank God for all,” he wrote to his brother Ferdinand, “and hope that after this disaster He will grant us of His great goodness, some great good fortune,” and he refused to accept the inevitable conclusion that he had sailed too late. As regards the sudden storm, he wrote that “nobody could have guessed that beforehand. It was essential not so much to rise early, as to rise at the right time, and God alone could judge what time that should be.” Any shrewd observer of the Maghreb coast would have begged to differ. Charles never went crusading at sea again. The following year he departed for the Netherlands to confront the intractable problems of the Protestant rebellion and another French war.

CHAPTER

6

The Turkish Sea

1543–1560

I

T WAS CLEAR BY THE

1540

S

that Charles was losing the battle for the sea. The debacle at Preveza had slammed shut the possibility of effective Christian cooperation; the disaster at Algiers confirmed the city as the capital of Islamic corsairing, to which adventurers and converted renegades now flocked from all over the Mediterranean to plunder Christian coasts and shipping lanes.

In this atmosphere, nothing shocked and terrified Christian Europe as much as the extraordinary scenes along the French coast in 1543–1544. France and Charles were at war again, and Francis had moved to further strengthen his alliance with Suleiman. Barbarossa was invited to join forces with the French. Together they sacked Nice, a vassal city of Charles’s; in the winter of 1543, to the scandal of Christendom, Barbarossa’s lean predatory galleys were rocking safely at anchor in the French port of Toulon. There were thirty thousand Ottoman troops in the town; the cathedral had been converted into a mosque and its tombs desecrated. Ottoman coinage was imposed and the call to prayer rang out over the city five times a day. “To see Toulon, one might imagine oneself at Constantinople,” one French eyewitness declared. It was as if the Orient had complicitly invaded the Christian shore. Francis, who styled himself the Most Christian King, had agreed to supply Barbarossa’s fleet with food over the winter and to augment his forces—in return for the Ottoman fleet pillaging Charles’s realms. In practice it was the people of Toulon who were obliged to foot the bill for their unwelcome visitors.

This strange cohabitation was soon soured by bad faith on both sides. Francis dithered and prevaricated in his wholehearted commitment to an alliance that shocked Europe. Barbarossa was contemptuous of his ally’s faintheartedness, kidnapped the whole French fleet, and held it to ransom. The French began to feel that they had made a pact with the devil; Francis eventually had to pay Barbarossa eight hundred thousand gold ecus to depart, leaving the people of Toulon poverty-stricken but relieved.

As the Ottoman fleet sailed off to Istanbul in May 1544, they were accompanied by five French galleys on a diplomatic mission to Suleiman. Among those who went was a French priest, Jérome Maurand. The classically minded cleric volunteered for the voyage as chaplain; he was enthusiastic about the opportunity to see Constantinople and the great remains of the classical world along the way.

In his journal Maurand recorded the natural and man-made wonders of the Mediterranean from the deck of a galley. He witnessed the terrifying spectacle of lightning storms at sea and the eerie glow of Saint Elmo’s fire shimmering from the mast; he saw the ruins of Roman villas still radiantly painted in blue and gold, and sailed past the volcano of Stromboli in the dark, “ceaselessly spewing out fire and enormous flames.” He marveled at the sand of the island of Volcanello, “black as ink,” and peered over the rim of its bubbling, sulfurous crater, which conjured up the gulf of hell. At the Ottoman port of Modon, in southern Greece, he inspected an obelisk constructed entirely of Christian bones and put ashore at the ancient site of Troy before finally reaching “the famous, imperial, and very great city of Constantinople” with a salute of gunfire as the galleys passed the sultan’s palace. Along the way he was also an unwilling witness to the might of Ottoman sea power.

The imperial fleet with which Suleiman had provided Barbarossa—one hundred twenty galleys and support sailing vessels—rampaged down the west coast of Italy with unstoppable force. Charles’s coastal defenses had no answer to such a heavily armed and mobile enemy. At word of Barbarossa’s approach, people simply fled. Empty villages were burned to the ground; sometimes the invaders would follow the fleeing populace several miles inland. If the people retreated into a secure coastal fort, the galley captains turned their prows to the shore and pulverized the walls or dragged the cannon ashore and instigated a major siege for as long as it took. Barbarossa’s men had no fear of counterattack. Only a few small detachments of Spanish soldiers guarded isolated towers. Out at sea, Doria’s nephew, Giannetto, tracked the fleet with his twenty-five galleys but was forced to scurry back to Naples at any sign of an engagement.

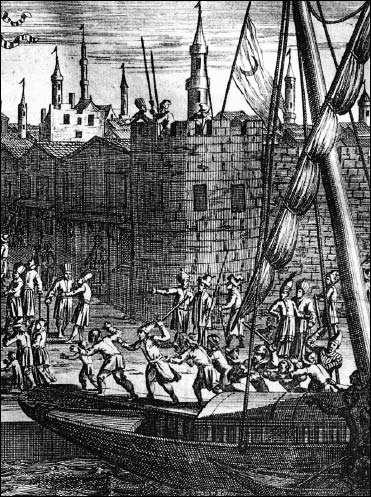

Day after day Maurand watched the fleet at work. A combustible mixture of jihad, imperial warfare, personal plunder, and spiteful revenge fueled their rampage. The priest witnessed slave-taking on an enormous scale. From each assault, long lines of men, women, and children were led down to the shore in chains, where they risked the equal perils of the sea. Sometimes a coastal village would try to bargain part of its population in a cruel lottery. Port’Ercole offered eighty people, to be chosen by Barbarossa, in return for thirty going free. He accepted the bargain but torched their village anyway. Only one house was left standing. Fortifications were destroyed as a matter of course. Finding Giglio deserted, the seamen razed it, but the castle resisted and had to be blasted into submission and ruined. The 632 Christians who surrendered were enslaved, but their leaders and priest were beheaded in front of Barbarossa to discourage resistance. It was a calculated and effective means of breaking morale. “It’s an extraordinary thing,” Maurand testified, “how the very mention of the Turks is so horrifying and terrible to the Christians that it makes them lose not only their strength but also their wits.” Barbarossa employed the exemplary brutality of Genghis Khan.

Some of his reprisals were acts of personal revenge, conducted even beyond the grave. Singling out the coastal town of Telamona, he had the body of the recently deceased Bartolome Peretti ripped from its tomb, ritually disemboweled, chopped into pieces, and burned in the public square, along with the corpses of Peretti’s officers and servants. When Barbarossa left, the smell of burned flesh hung in the air. The terrified populace crept from their hiding places shaken and appalled. It was payback for Peretti’s attack on Barbarossa’s home island of Lesbos the previous year, when his father’s house had been destroyed.

The Ottomans sailed on. The fleet burned several villages on the island of Ischia and took two thousand slaves. Naples crouched behind its shore guns as the fleet swept past like a black wing darkening the sun. Salerno, farther south, was saved only by a miracle. The galleys were closing in after dark, so near that Maurand could see the lights in the windows, when “God in his mercy” intervened. A sudden storm arose and there was “a cruel sea from the southwest and a blackness so thick that the galleys couldn’t see one another, together with a rain falling without ceasing from the sky that was quite unbearable.” The Christian slaves, huddling on the exposed deck like “drowned ducks,” were cruelly beaten. One galliot, overloaded with captives, foundered in the storm: “They all drowned, except for some Turks who escaped by swimming.”

Unloading slaves at Algiers

The last straw for the increasingly appalled French contingent came at Lipari, the largest of the volcanic islands off the coast of Sicily. The Lipariots had been warned of the approaching fleet. They strengthened their defenses but declined to evacuate the women and children and withdrew into their well-prepared fortress. Hayrettin landed five thousand men and sixteen cannon and settled down for a long siege. As he blasted away, the defenders tried to negotiate; when they offered fifteen thousand ducats, Barbarossa demanded thirty thousand and four hundred children. Eventually they thought they had brokered a deal with a payment to be made for each person. They gave up the keys to the castle, but he enslaved them all anyway, except for the richest families, who paid sizeable ransoms for their liberty. The ordinary people were ordered past the implacable pasha one by one. The old and useless were beaten with sticks and released. The rest were chained and marched down to their own harbor. A few of the most aged were found sheltering in the cathedral church. The corsairs seized them, stripped off their clothes, and cut them open while still alive, “out of spite.” Maurand was totally unable to comprehend these actions. “When we asked these Turks why they treated the poor Christians with such cruelty, they replied that such behavior had very great virtue; that was the only answer we ever got.” Nor could the priest understand why God permitted such sufferings; he could conclude only that it was because of Christian sin, in the case of the Lipariots because they were said to be “much given to sodomy.”

Profoundly shaken, the French ransomed a few of the Lipariot captives at their own expense and watched the rest being led away, seeing “the tears, groans, and sobs of the pitiful Lipariots leaving their own city to be led away into slavery; fathers looking at their sons, mothers their daughters, were unable to hold back the tears in their sad eyes.” Charles at Tunis, Hayrettin at Lipari: the battle for the Mediterranean had become a war waged against civilians. The castle, the cathedral, the tombs, and the houses were ransacked and burned. Lipari was a smoking ruin. While Barbarossa arranged a truce and offered to sell his new captives back in nearby Sicily, the French galleys made their excuses and sailed on alone.

In the summer of 1544 Barbarossa took some six thousand captives from the coasts of Italy and the surrounding seas. On his way home the boats were so dangerously overloaded with human cargo that the crews threw hundreds of the weaker captives overboard. He entered the harbor in triumph to the firing of cannon and nighttime fires illuminating the Horn. Thousands of people gathered on the shore to witness the triumphant return of “the king of the sea.” It was to be his last great expedition. In the summer of 1546, at the age of eighty, he was carried off by a fever in his own palace in Istanbul to the universal mourning of the people. He was buried in a mausoleum on the shores of the Bosphorus that became an obligatory place of pilgrimage for all departing naval expeditions, saluted with “numerous salvoes from cannon and muskets to give him the honor due to a great saint.” After so many decades of terror, Christians could scarcely believe that “the king of evil” was gone; so great was the superstitious dread attached to his name that legend persisted he could leave his tomb and walk the earth with the undead. Apparently it took a Greek magician to fix the problem: burying a black dog in the tomb appeased the restless spirit and returned it to Hades.

And in a real sense Barbarossa returned unceasingly to terrorize the Christian shore. A new generation of corsair captains sprang up in his wake; the greatest of whom—Turgut, Dragut to the Christians, born on the Anatolian coast—would replicate the career of his mentor, moving from enterprising freebooter on the shores of the Maghreb and battle experience at Preveza to imperial service under Suleiman during the twenty years after 1546. The king of evil had sowed dragon’s teeth in the sea.

Barbarossa’s last great raid of 1544 had shown that Muslim fleets could roam at will. These huge sweeps were campaigns in a full-scale Mediterranean war that the Ottomans were winning. Slave-taking was an instrument of imperial policy, and the damage was immense. In the four decades following the launch of Barbarossa’s first imperial fleet in 1534, thousands of people were snatched from the coasts of Italy and Spain: eighteen hundred from Minorca in 1535, seven thousand from the Bay of Naples in 1544, five thousand from the island of Gozo off Malta in 1551, six thousand from Calabria in 1554, and four thousand from Granada in 1566. The Ottomans could apply sudden and overwhelming force at precise points; they could land at and destroy fair-size coastal towns with impunity and threaten even the major cities of Italy. When Andrea Doria’s nephew trapped and captured Turgut on the Sardinian shore in 1540 and condemned him to the galleys, Barbarossa threatened to blockade Naples unless Turgut was ransomed; the Genoese thought it wisest to comply. Doria and Barbarossa met in person to agree the terms. The thirty-five hundred ducats would prove a bad bargain for the Christians: eleven years later Turgut would blockade Genoa himself. The Christians had no adequate naval presence to respond to such threats after Preveza. Charles was too busy attending to multiple other wars to frame—or pay for—a coherent maritime response. By now it was all that the Dorias could do to apply some counterpressure.

Nor was this assault conducted just through large fleet actions. War between Charles and Suleiman ebbed and flowed, depending on the timing of their conflicts, but when they signed a peace in 1547 so that the sultan could campaign in Persia, the big maritime expeditions were temporarily suspended; warfare continued anyway under another name. Enterprising corsairs from the Maghreb filled the vacuum and inflicted a different style of misery on Christian shores. Where the imperial fleets had brazenly smashed their way through local defenses, these lesser carnivores proceeded by ambush and stealth. It was a subtler kind of terror. Surprise replaced brute force.