Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (14 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

And yet there were uneasy notes. Despite deep planning, the expedition had been hastily assembled to catch the spring wind. Had the Ottomans properly calculated the risk? Had they marshaled enough men? Had it all been too rushed? Within a few days some of the vessels had to be recaulked and their keels greased again. One huge ship foundered off the coast of Greece with the loss of several hundred men and valuable supplies of gunpowder. There had been the usual difficulties making up the full complement of oarsmen.

Nor was the venture universally popular. The soldiers, particularly the dismounted cavalry, disliked long sea voyages, and the rumor was that the fight would be tough; some paid to be excused. Criminals had to be pardoned to make up the numbers. All this was summed up in a remark attributed to the grand vizier, Ali, staying complacently at home beside the sultan, that hinted at both the risk and the fault lines in the command structure. Watching Mustapha and Piyale step aboard their ships, he quipped ironically, “Here are two good-humored men, always ready to take coffee and opium, about to take a pleasure trip around the islands together.” In its haste to depart, the fleet had also omitted an important ritual. It had failed to make the customary visit to the tomb of Barbarossa on the shores of the Bosphorus, the talisman of naval success.

CHAPTER

8

Invasion Fleet

March 29 to May 18, 1565

P

ROFESSIONAL TURK WATCHERS

within the city dispatched hurried memoranda west on a daily basis. “On the morning of March 29 the admiral of the fleet and Mustapha the overall commander went to kiss the sultan’s hand and to receive their authorization,” read the breathless dispatches from the banking house of Fugger. “It’s not yet known where the fleet is heading but the word is it will go to besiege Malta.” Eight hundred miles away in Malta, muffled news of this activity had reached La Valette before the end of 1564—the knights had their own sources of information in all the key listening posts of the sea. In January the grand master gradually stirred into action.

Whether it was because of the years of phony war—there was hardly a spring when the Ottoman fleet did not threaten an expedition west—or the possibility that the Muslims might be aiming for La Goletta, or a shortage of cash, or La Valette’s personal indecisiveness, is unclear, but everything necessary for the island’s defense was happening almost too late.

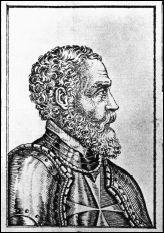

In the spring of 1565 the grand master was seventy years old. Behind him lay a lifetime’s unbroken service to the Order. Unique among knights, from the time he had donned the Order’s surcoat at the age of twenty, he had never returned to his family home in France. He had given everything to warfare in the name of Christ—he had been badly wounded in a fight with Barbary corsairs, been captured and spent a year as a galley slave, served as captain general of galleys, and as governor of Tripoli. As a man born in the fifteenth century, La Valette harked back to the feudal crusading spirit: stern, unyielding, fiery, imbued with a sense of Christian mission that deeply irritated the Venetians. “He is tall and well made,” wrote the Italian soldier Francisco Balbi, “of commanding presence, and he carries well his dignity of Grand Master. His disposition is rather sad, but, for his age, he is very robust…he is very devout, has a good memory, wisdom, intelligence, and has gained much experience from his career on land and sea. He is moderate and patient and knows many languages.” Despite Balbi’s observations, there were indications that La Valette was no longer a young man: his large, shaky signature suggests someone at least short-sighted—and he gave signs of particular cautiousness with regard to expensive preparations for an uncertain war. Now, almost too late, panicky work was put in hand for Malta’s defense. The security of the island rested, as at Rhodes, on the implacable defense of fortified places, but in early 1565 these defenses left something to be desired.

La Valette

The key to Malta was the extraordinary natural harbor on the eastern side of the island, a complex series of inlets and small peninsulas that cut their way four miles back into the island and provided a series of magnificent sheltered anchorages. Here on two small adjacent promontories, jutting out into the great harbor like stone galleys tethered to the shore, the knights had established their strongholds. The first of these, Birgu (the town), was the knights’ own fortress, encircled in familiar style with bastioned walls and a deep ditch. It was a small site, a thousand yards long, that tapered to a point, where a stout inner castle, Fort Saint Angelo, commanded the water. The second promontory, Senglea, separated from Birgu by a strip of water three hundred yards wide, was less developed but was similarly guarded by a fort, Saint Michael, at the landward end. As a defensive system these tongues of land were interdependent. The creek between provided a secure harbor where the knights kept their galleys; in the spring of 1565 this harbor also held the chief eunuch’s prized galleon. Its mouth could be closed by a chain at its seaward end and the two settlements connected across the creek by a pontoon bridge. The problem in the spring of 1565 was that neither Birgu nor Senglea had complete fortifications on their landward side.

Worse still the terrain was unfavorable. Both settlements were commanded not only by higher land behind them but by the heights of a much higher peninsula across the water, called Mount Sciberras, which was the strategic key to the whole harbor. Sciberras overlooked both Birgu and Senglea on one side and a symmetrical deepwater harbor, Marsamxett, on the other. Over the years a succession of visiting Italian military engineers had strongly recommended that the knights should build a new stronghold and capital on Sciberras; it afforded total control of the only secure anchorages on the island and would render the knights virtually invulnerable to attack. No move had been made to act on this advice; all that had been done was the hasty construction of a small star-shaped fort, Saint Elmo, at the tip of the peninsula to provide some security for the harbors.

As La Valette surveyed his defenses, it was clear that all three strongholds—Birgu, Senglea, and Saint Elmo—were unfinished and needed urgent attention if they were to provide any kind of contest for the experienced Ottoman siege gunners. In the early months of 1565, the knights swung slowly into action. There was much to do.

THE TOTAL NUMBER

of military knights in the Order was about six hundred—few more than at Rhodes half a century earlier—and many of these were scattered across Europe. On February 10, the grand master issued a summons for all knights to report to the island; about five hundred made it before the siege began. In times of war, the knights traditionally relied on paid troops and levies of local men as an extra source of manpower. In January, La Valette set about the arrangements for hiring soldiers; these were to be Spanish and Italian contingents released by the king of Spain, as well as mercenaries, but the process of assembling and transporting these troops from the Italian mainland and Sicily was a slow process, and in the end few of them arrived in time. The third component of his force, the Maltese militia, La Valette had little regard for. “A people of little courage and with little love for the Faith,” he called them, “a people that as soon as they see the enemy are terrified just by the shots from the arquebus—how much greater their terror will be at the cannon balls that will kill their women and children.” As it turned out these slighting comments were wholly unjustified. The Maltese would provide the majority of the fighting men and they would prove to be totally reliable.

At the same time the search for provisions intensified. Within the island, huge quantities of water were transported to Birgu and Senglea in clay bottles, and ships were dispatched to Italy to buy food. It was not easy: there was famine in the Mediterranean and grain was short. Romegas took to detaining luckless cargo ships in the Malta channel and requisitioning their contents. There was a forcible evacuation of noncombatants: women and children, the elderly, freed Muslims, and prostitutes were carried away to Sicily, though many of the civilian Maltese successfully petitioned to be allowed to stay. Siege materials, armaments, and food were shipped back: “hoes, picks, shovels, hardware, baskets,…bread, grain, medicines, wine, salted meat, and other provisions.” Grain was poured into cavernous underground chambers and sealed with stone plugs. A trickle of soldiers arrived: Spanish and Italian infantry, volunteer brigades assembled by enterprising adventurers called to the cause of Christendom, paid mercenaries recruited by the Order’s functionaries in Italy. The straits between Malta and Sicily were busy with shipping. Work was started to complete the wall encircling Senglea and to strengthen the bastions on Birgu, but it proceeded slowly. Materials had to be imported from Italy and labor was in short supply. La Valette levied the services of the Maltese, both men and women, and the knights themselves, including the grand master, put in a couple of hours a day to set a suitable example. At the same time La Valette wrote to the king of Spain, his temporal overlord, and the pope, his spiritual one, requesting men and money.

EVERY STATE IN THE

Christian Mediterranean watched the progress of the Turkish armada with bated breath. Messenger boats sped across the sea with news. For Philip it was clear that this was war against Spain by proxy: “The Turkish fleet will be coming with more galleys than in past years,” he wrote on April 7. The arsenals of Barcelona were working at full stretch and, in a tide of rising panic, he ordered an inventory of private ships as a last-ditch defense. The Ottoman fleet was moving fast to strike early in the year, beating a path around Greece to take on board food, water, and men at prearranged collection points. On April 23 the fleet was at Athens, on May 6 at Modon in southern Greece, on May 17 the local commander at Syracuse in Sicily dispatched a posthaste messenger to the viceroy: “At one in the morning, the guard at Casibile fired thirty salvoes. For them to fire so many it must, I fear, be the Turkish fleet.”

There was a rising tide of panic throughout the sea. Everyone understood the importance of Malta, if Malta it were to be. The diplomatic exchanges resounded with the knowledge of a supreme crisis, but Europe rang to the same old drumbeat: disunity and mutual suspicion. The possibility of a united response to the infidel was as remote in 1565 as it had been at Rhodes in 1521 and Preveza in 1537. Pope Pius IV thundered for a Holy League against the infidel and was bitterly disappointed by the response. He gifted large sums of money to Philip to build galleys, yet nothing seemed to be forthcoming. The king of Spain “has withdrawn into the woods,” the pope complained, “and France, England and Scotland [are] ruled by women and boys.” The danger was huge and the support minimal. He saw that the sultan “must be coming to do harm to us or to the Catholic King [Philip II], that the armada was powerful, and the Turks valiant men, who fight for glory, for empire, and also for their false religion.” They had nothing to fear, “considering our small resources and the division of Christendom.” In the meantime he promised what help to the knights that he could.

Yet Philip, despite a crippling natural caution, had not been inactive. The Spanish were running hard to rebuild their fleet after the disaster at Djerba. In October 1564 he appointed his captain general of the sea, Don Garcia de Toledo, as viceroy of Sicily. This gave him oversight of the whole central Mediterranean and the defense of Malta. Don Garcia, a man “serious, of good judgement and experience,” had a sound strategic grasp of the issues, but was shackled by insuperable difficulties. He lacked the coordinating resources and central bureaucracy of the Ottoman state. The Spanish fleet was a coalition of four squadrons—those of Naples, Spain, Sicily, and Genoa—and still reliant in part on private galley contractors such as the Dorias. The task of bringing these forces together in one place with their full complement of rowers and soldiers, munitions and stores, was a daunting one—while at the same time these squadrons were needed to protect Spain and Southern Italy from random corsair attacks. While the Ottomans sailed on a calm sea, the gathering Spanish squadrons had to contend with much more taxing winds in the Western Mediterranean. By June 1565, a month into the siege, Don Garcia had still managed to assemble only 25 galleys; the Ottomans came with 165. Philip’s man was bound to be careful; the annihilation of his nascent fleet could have disastrous consequences for Christendom. However, he started to gather men and resources on Sicily against the eventuality of an Ottoman attack.

On April 9, Don Garcia, with thirty galleys, made the short thirty-mile voyage from Sicily to confer with La Valette. The two commanders toured the defenses of Birgu and Senglea together. Then Don Garcia demanded an inspection of the star fort of Saint Elmo on the tip of Sciberras. The shrewd old Spaniard immediately pinpointed the strategic importance of this small fortification. In his opinion it was the key to the whole defense. The enemy would be sure to target it early in order to secure a safe anchorage for their fleet and to bar seaborne relief for Birgu and Senglea. It was the pivot “on which the salvation of all the other fortresses on the island depended.” It was essential “to make every effort to protect and conserve it for as long as possible” in order to wear down the enemy and allow sufficient time for a serious relief force to be assembled. Yet the whole structure was deficient: it was too small to accommodate many men and guns; it was poorly built and lacked suitable parapets. Don Garcia studied the terrain in microscopic detail and identified a specific weakness. On the western side, above the sea, one flank was patently vulnerable to attack: “The enemy could get in here without any difficulty.” He recommended the urgent construction of a further flanking fortification—in the language of the siege engineers, a ravelin—a triangular-shaped external fortification to protect that section of wall, and detailed his military engineer to oversee the work.