Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (24 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

A reconstruction of the land front of Saint Elmo, seen from the Ottoman trenches. The cavalier looms over the fort from behind.

RECONSTRUCTION BY DR. STEPHEN SPITERI

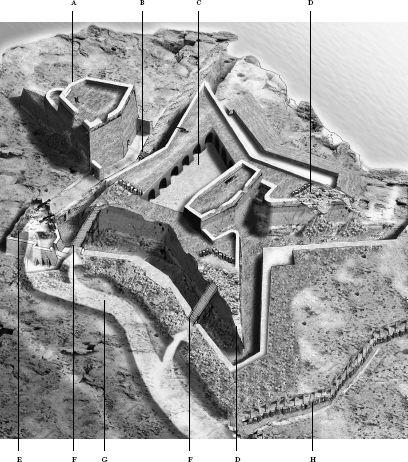

An aerial reconstruction of Saint Elmo under attack: a) the cavalier, b) drawbridge into the fort, c) central parade ground, d) the points of the stars pounded into rubble, e) the ravelin, captured on June 3 and furnished with two guns, f) Ottoman bridges, g) route of the Ottoman assault, h) the forward Ottoman trench.

RECONSTRUCTION BY DR. STEPHEN SPITERI

August 7, 1565: the moment of supreme crisis for Christian Malta. Ottoman arquebusiers in turbans and white headdresses try to storm the post of Castile and plant their flags on the wall. They are met by counterfire from the well-armed knights. La Valette stands, suicidally visible, at center foreground.

NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, LONDON

A nineteenth-century print of the fall of Famagusta. Bragadin, tied to an ancient column that stands to this day, is prepared for a ghastly death. Lala Mustapha Pasha watches from a balcony.

MUSEI CIVICI VENEZIANI, MUSEO CORRER, VENICE

The victorious commanders at Lepanto: from left, the dashing Don Juan of Austria, Marc’Antonio Colonna, and Sebastiano Venier, the gruff Venetian lion.

AKG-IMAGES/ERICH LESSING

The tomb of Barbarossa on the shores of the Bosphorus.

ROGER CROWLEY

A modern reconstruction of the

Real,

Don Juan’s flagship, showing the highly decorated stern.

MUSEU MARITIM ATARAZANAS, BARCELONA, CATALUNYA, SPAIN, KEN WELSH/THE BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

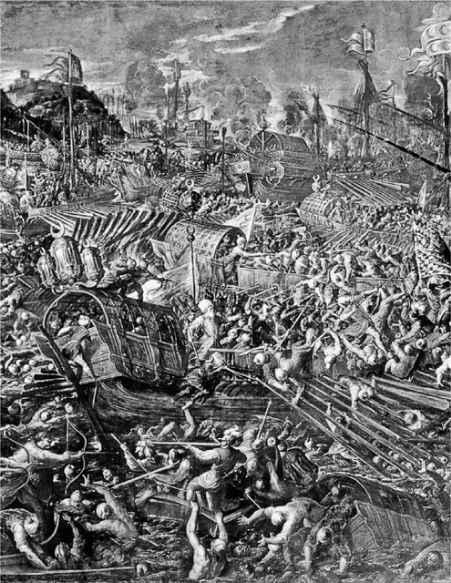

“It’s as if men were extracted from their own bodies and transported to another world”: Vicentino’s great painting of Lepanto summons up the smoke, noise, confusion, and shattering impacts of the battle. Violent death is meted out randomly by guns, arrows, pikes, swords, and the sea itself. The water is matted with corpses. Ali Pasha on the

Sultana,

center, rallies his men to fight to the finish.

AKG-IMAGES/PALAZZO DUCALE, VENICE

Throughout August, slogging trench warfare continued around the post of Castile. The Ottomans attempted to snake trenches forward, prepare mines, mount diversionary attacks, and scale walls. They laid down a blanket of fire for days at a time. The Christians responded with surprise sallies and constant observation. Both sides lodged snipers behind makeshift barricades and hunted their enemy. It was almost a form of sport, “an enjoyable game hunt.” On August 12 the Ottomans shot dead Marshal de Robles, one of the iconic heroes of the defense, who had been peering incautiously over a parapet without his bulletproof helmet. The defenders took to smearing their bullets with fat; as the bullets hit their victims, they also set the Turks’ robes alight. When the Muslims tried to recover their dead, which they invariably did, they became sitting targets. The unyielding La Valette forbade his men to attempt to do likewise—it was simply too expensive. In the rubble of the walls men sniped at one another; hurled hand grenades, rocks, and incendiaries; hit one another at close range with field guns; jumped into one another’s positions with sabres and scimitars. They were so close—sometimes no more than twenty paces apart—that they could call to each other. Renegade Christians now took to shouting encoded messages of support to their coreligionists. At moments, something like a fellow feeling developed among men on opposite sides of a single embankment enduring the same fate.

The days pass in a blur of violence and death, noise and smoke, the clanging of Christian church bells, the sound of the Muslims praying in the dark before each attack. Men die in a hundred ways. They are shot through the head, or burned alive by incendiaries or cut down by a blade or blown into fragments by a cannonball. The positioning of banners becomes an obsession. The Ottomans raise green and yellow flags on the parapet, red ones with horsetails—the defenders try to tear them down. The battle for these markers of territory is as fierce as the struggle to recover the body of a dead commander. Flags raise morale; their loss is a signifier of ill omen. On August 15 the standard of the knights is shot down on the post of Castile; the Muslims in the trenches take it as an omen of impending victory. When they are forced back on August 18, a soldier on the ramparts grabs the red-and-white flag of Saint John and runs the length of the walls “out of sheer joie de vivre,” so fast “that an infinite number of arquebuses can’t touch him.” No one wants to be taken alive; capture inevitably means torture, and both sides despoil the enemy dead, acting out rituals stretching back to the Mediterranean bronze age—Achilles dragging Hector around the walls of Troy.

MUSTAPHA WAS PUSHING HIS MEN

as hard as he could for one more major assault. Four days of bombardment from August 16 to 19 were followed by sullen dissent from the janissaries. They refused to leave the trenches unless he led the way. The pasha was no coward. He led the charge—and swelled the numbers of crack troops by dressing up camp servants as janissaries, and promising them promotion if they fought well. The fighting was fierce, but to no avail; Mustapha had his turban knocked from his head and fell to the ground, stunned. Both sides were drawing on their last reserves of strength; Mustapha started to siphon off the fleet’s resources of gunpowder. La Valette presented himself at the infirmary and requested a muster of the sick and wounded; those able to walk were judged fit to fight. The same day an arrow was shot over the wall with a one-word message attached: Thursday—warning of yet another attack. It was beaten back.

The siege was grinding slowly to a halt in a murderous stalemate, similar to the impasse at Rhodes forty years earlier. The councils in Mustapha’s ornate tent became longer and more heated; the pasha wanted to follow the example of Suleiman at Rhodes, and continue a winter campaign. Piyale flatly refused. The fleet was far from home. It was impossible to repair it over the winter on Malta, and the enemy was close. One or two more attacks and they would have to head back to Istanbul. Mindful of Suleiman’s warnings, on August 22 they planned yet more assaults. Huge prizes were offered for bravery and success. On Saturday, August 25, it started to rain.

CHAPTER

14

“Malta Yok”

August 25 to September 11, 1565

T

HE NORTH WIND

that the Italians called the tramontana, “the sunset wind,” is brewed in the Alps. It sweeps down the length of Italy, bringing heavy rain and squally sailing conditions to the central Mediterranean. In late August 1565 the tramontana hit Malta with torrential downpours—the first indications of winter.

The rain heightened a scene of unrelieved devastation. After three and a half months of fierce fighting, the harbor area had been reduced to an apocalyptic wasteland. The defenses of Birgu and Senglea had been literally pulverized; heaps of rubble were all that separated the two sides. The Ottomans crouched miserably in their waterlogged trenches, the Christians behind makeshift barricades. Each front line was marked by tattered flags and the rotting heads of their enemies. Though the Muslims worked hard to carry away their casualties and bury them in mass graves dug with enormous effort from the solid rock on Mount Sciberras, it was a landscape of death. Snipers, cannon, swords, pikes, incendiaries, malnutrition, waterborne diseases had all taken their toll. By the end of August, perhaps ten thousand men had died in the equatorial summer heat. Bloated corpses bobbled gaseously in the harbor or lay dismembered across the battlefield after each successive attack. The Ottoman camp at Marsa was fetid with sickness; the air stank of rotting flesh and gunpowder. Both sides were hanging by a thread.

Within the Christian compounds, there was a sense that one more concerted attack could finish them off. “Our men are in large part dead,” wrote the knight Vincenzo Anastagi, “the walls have fallen; it is easy to see inside, and we live in danger of being overwhelmed by force. But it is not seemly to talk of this. First the Grand Master, then all the Order, have determined not to listen to anything [defeatist] that is whispered outside.” It did indeed seem that only the willpower of La Valette was keeping the defenders alive. When it was suggested on August 25 that Birgu could no longer be defended and that they should retreat to the fort of Saint Angelo at the tip of the peninsula to make a last stand, La Valette had its drawbridge blown up. There would be no retreat. Rounds of church services and thanksgiving prayers for each successful defense fortified the morale of the people.

At the front line it was impossible for the defenders to show their heads over the parapet without being shot. At times only heavy-duty siege armor kept them alive. On August 28 an Italian soldier, Lorenzo Puche, was talking to the grand master when he was hit in the head by an arquebus shot. His plate helmet took the full force of the blast. The man fell to the ground stunned, picked up his dented headgear, and asked permission to carry on with a sortie—under the circumstances it was refused. To lessen the risks from sniper fire, arquebuses were lashed together, hoisted above the parapet on poles, and fired remotely by long strings.

The two sides were in places only feet apart, crouching behind their barricades in the rain. “We were sometimes so close to the enemy,” recalled Balbi, “that we could have shaken hands with them.” Commanders on both sides noticed—and feared—the sense of common suffering across the front line. At Senglea it was reported that “some of the Turks talked to some of our men and they developed the confidence to discuss the situation together a bit.” These were brief moments of mutual recognition, like footballs kicked into no-man’s-land. On August 31, a janissary emerged from his trench to present his opposite numbers with “some pomegranates and a cucumber in a handkerchief, and our men gave back in exchange three loaves and a cheese.” It was a rare moment of common humanity in a conflict devoid of chivalry. As the two groups of men talked, it transpired that morale in the Ottoman camp was dropping. Food supplies were dwindling, the situation was at stalemate with the defenders repairing the breaches as fast as they were made; the friendly janissaries gave the impression that it was now a common belief in the Ottoman camp “that God did not want Malta to be taken.”

The rain probably dented Ottoman morale more; La Valette issued his men with mats of woven grass to protect themselves from the wet, and the change in the weather altered the dynamics of the siege. Mustapha knew that time was running out. The councils in the pasha’s ornate tent became heated and recriminatory. All the old arguments were picked over again: Could they overwinter? What would the sultan do if they retired without a victory? How serious were the rumors of a rescue fleet?

Piyale again refused to countenance overwintering, but peremptory orders were sent out to strengthen marine patrols of the island: “Due to the urgent need to guard and watch the regions of the island of Malta, I have ordered that you set up a mission to guard and watch around the island by means of 30 galleys…. You are to punish whoso-ever opposes or contradicts your words, by a fitting punishment.” At the same time, the wet weather provided Mustapha with an opportunity. Heavy rain doused the fire of arquebuses and other incendiaries. It provided a chance to tackle the defenses without answering gunfire.

In the last days of August the pashas threw everything into a series of desperate assaults in the driving rain. Miners were set to work planting explosive charges under the walls; siege towers constructed; handsome rewards offered for success. The pashas moved their tents closer to the front line to inspire the men, and Mustapha led attacks in person. He sensed again and again that the ultimate prize was almost within reach; yet it continually eluded him. The defenders were still fighting with spirit, countermining, leading sorties, shooting down Mustapha’s wooden siege engines. When it was too wet to use their arquebuses, La Valette issued the men with mechanical crossbows from the armory. The Ottomans were unable to use their conventional bows in the rain, but the crossbow—an anachronistic device from medieval warfare—caused heavy damage. They were so powerful, according to Balbi, “that their bolts could pierce a shield and often the man behind it.”

On August 30 it rained all morning and Mustapha led a determined attempt to clear the breaches of fallen stone, then to storm through the opening. Some Maltese ran to La Valette shouting that the enemy had got into the city. La Valette hobbled there in person as fast as he could with all the men he could muster, together with the women and children hurling rocks down on the onrushing men. They were probably saved only by the weather. The rain stopped; the defenders were able to use incendiaries and guns to drive the enemy back. Mustapha was struck in the face but remained resolute; according to the Christian sources, “stick in hand, he began furiously to urge his men on.” They fought from noon until nightfall, to no avail. The attack faltered. The following day, the defenders braced themselves for yet another attack, but none came. “They did not move for they were exhausted as we were,” Balbi recorded. The whole siege had ground to a halt. By now Mustapha knew that a Christian rescue fleet would soon be on its way from Sicily. He offered lavish rewards for victory: for the men promotion to the salaried rank of janissary, for the slaves freedom. It made little difference.

Mustapha was not the only commander growing anxious to discern, and fulfill, his sovereign’s wishes. Malta was a struggle for the Mediterranean fought by proxy—peering over the shoulder of the combatants were the looming figures of Suleiman and Philip II, like dominant figures at either end of a chessboard. In Sicily, Don Garcia waited anxiously for permission from Madrid to mount a rescue bid. By early August he had collected eleven thousand men and eighty ships on Sicily; the men were largely hardened Spanish troops, pikemen and arquebusiers, together with a small band of Knights of Saint John and some gentleman adventurers—freelancers come to fight for the glory of Christendom. Among those who failed to make it in time was Don Juan of Austria, Philip’s illegitimate half brother. The military force was to be led by Don Alvare Sande, the commander at Djerba, ransomed back from Istanbul, and a famous condottiere, the one-eyed Ascanio della Corgna, who had been released by the pope from prison, where he was being held for murder, rape, and extortion. Apparently one could be lenient in the cause of Christendom. They were ready to depart, and Don Garcia was being assailed by furious requests to sail. Daily the reports became more desperate. “Four hundred men still alive…. Don’t lose an hour,” wrote the governor of Mdina on August 22. Yet Philip dawdled in an agony of indecision, and when permission finally reached Don Garcia on about August 20 it was hedged about with caveats. A rescue attempt could be mounted “providing it could be done without any real danger of losing the galleys.” There must be no clash with the Ottoman fleet. It was an almost impossible injunction. After lengthy deliberations, the decision was taken to pack their force into the sixty best galleys, make a dash for the Malta coast, drop the men, and then retire. To increase their chances of evading detection, they would make an approach from the west, feinting an attack on Tripoli.

The rescue force set sail from Syracuse on the east coast of Sicily on August 25 and immediately found themselves sailing into the teeth of the gales that were striking Malta. August 28 saw the fragile galleys snouting into a breaking sea, dipping and plunging, the rain falling in sheets, so that the men were drenched “from the water both from the sky and the sea” the fighting spurs were ripped off the ships, oars snapped, masts shattered. With the boats in danger of foundering, the landlubber soldiers, cold and terrified, turned to prayers and the promise of votive offerings. The spectacle of Saint Elmo’s fire flaring in blue and white jets from the masts added to their alarm, along with the date: it was the day of the decapitation of John the Baptist, a particularly ill-omened marker in the church calendar. Somehow the whole convoy survived the night and was blown far off course to Trapani on the west coast of Sicily. It was to be the start of a nightmarish week of missed rendezvous and contrary winds that carried the expedition right around Malta, where they were sighted by the Ottoman fleet, and back to Sicily again. The soldiers, green and seasick from the whole experience, would have deserted to a man if Don Garcia had not forcibly prevented them. Finally on September 6 the fleet set out again to make a direct dash across the straits to try to catch the Ottoman fleet off guard. The ships departed in silence to cross the thirty miles of open water. Strict orders had been issued: the cockerels on the boats were to be killed, all instructions were to be given to the crews by voice rather than the usual whistles, and the oarsmen were forbidden to raise their feet—the rattling of chains carried far over a calm sea.

But the element of surprise had already been lost on September 3, when they were sighted by the corsair Uluch Ali, scouting off the west coast of Malta. The Christian relief force was now the subject of intense discussion in the pasha’s tent.

IN THE EARLY DAYS OF SEPTEMBER

it became apparent to the defenders that although the attacks continued, their tenor was changing. “They continued to bombard Saint Michael’s and the Post of Castile with equal fury,” wrote Balbi on September 5, “but with all their brave bombardment we saw them daily embarking their goods and withdrawing their guns. This afforded us great satisfaction.” The Ottomans were dragging their precious cannon away against the threat of a landing on the island. This was a long and laborious process that caused much trouble. Two giant bombards caused particular difficulty; one had come off its wheels and had to be abandoned. The other fell into the sea. Increasingly encouraging news leaked out to the defenders. They learned that some of the corsairs had taken their ships and sailed away; a boom had been placed over the mouth of the harbor to prevent further defections. At the same time a Maltese captive escaped back to Birgu. In the main square he publicly proclaimed that the Turks were so weakened they were leaving. Later, two more Maltese arrived with news that the enemy would give one more major attack then depart. On the night of September 6, hearing nothing from the enemy lines, a number of men crept into the Ottoman trenches. The trenches were completely deserted; they found just some shovels and a few cloaks. The whole force had been temporarily withdrawn to man the galleys against the possibility of attack.

Yet Mustapha had still not given up hope that victory might be snatched from impending failure. The untrustworthy Christian sources are the only record that we have of the final agonized debates in the pasha’s tent on the night of Thursday, September 6. Mustapha apparently reread a letter from Suleiman brought by a eunuch of the palace, of which we have no trace, stating that the fleet must not return from Malta without victory. What followed was an intense discussion about the sultan’s likely reaction. Mustapha was of the opinion that the nature of his master was so terrible that their end would be “miserable and horrible” if they returned from Malta without victory. Perhaps he recalled the execution of the cartographer, Piri Reis, killed on the sultan’s orders ten years earlier for a failed campaign in the Red Sea, at the age of ninety. Piyale, supported by one of the army commanders, demurred: Suleiman was the wisest and most reasonable of sultans; they had made superhuman efforts to capture the island; the weather had broken; it was most important to save the fleet; risking it now would hasten the destruction of the whole force. Mustapha declared himself ready to die in one more assault the following morning. If this failed, they would withdraw.

Mustapha had already given a specific order that suggested he was preparing himself for the inevitable. The chief eunuch’s huge galleon, taken by Romegas before the start of the siege, had been an ostensible cause of the whole campaign. It had rocked gently at anchor in the inner harbor the whole summer; Mustapha had sworn at the outset that it would be sailed back in triumph to Istanbul as proof of victory. Now on September 6 he ordered it to be sunk by gunfire. As the first shots came whistling across the water, La Valette had the galleon strapped to the quay with hawsers. It was holed but remained afloat.