Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (15 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Is it fair to ask of

Anything Goes

what we ask of some of the other musicals featured in this volume? What dramatic meaning does the work possess, and how is this meaning conveyed through Porter’s music? What, if anything, goes? In fact,

Anything Goes

is about many things, including the wrong-headedness of disguises and pretenses of various kinds and the unthinking attraction that common folk have for celebrities, even celebrity criminals.

Perhaps the central dramatic moral of

Anything Goes

is that sexual attraction and the desire for wealth exert a power superior to friendship and camaraderie in determining long-term partnerships. A few minutes into the play, for example, we learn that Reno has a romantic interest—or, as Sir Evelyn will later declare in his typical malapropian American English, “hot pants”—for Billy that has gone unreciprocated for years. In any event, although Billy thinks Reno is the “top” as well, he nevertheless enlists her help to wean Sir Evelyn from Hope, Evelyn’s fiancée at the beginning of the musical.

The final pairing of Hope with Billy and Reno with Sir Evelyn has some satisfying aspects to it. Billy brings out the “gypsy” in Hope and, because he stays on board the ship, he is eventually able to extricate Hope and her family from a bad marriage and financial ruin. For her part, Hope proves a positive influence in Billy’s life when she persuades him to drop his pretenses and confess that he is not the celebrity criminal Snake Eyes Johnson, even though he will be penalized by the rest of the ship, even temporarily imprisoned, for his newfound integrity. Reno rekindles Sir Evelyn’s dormant masculinity; Sir Evelyn will continue to entertain his future bride by his quaint Britishisms and distortions of American vernacular and, not incidentally, make an excellent provider for the lifestyle to which Reno would like to become accustomed.

But there is a darker side to the happily-ever-after denouement in this rags-to-riches Depression fantasy. Even though Hope appreciates Billy’s persistence and joie de vivre, she berates him for being a clown and will not speak to him until he confesses (at her insistence) that he is not Snake Eyes Johnson. More significantly, the main reason Reno rather than Hope remains “the top” is because Porter’s music for Reno is the top. For all his wealth, the non-singing Sir Evelyn might be considered the consolation prize.

Porter certainly cannot be faulted for giving nearly all his best songs in the show—“I Get a Kick Out of You,” “You’re the Top,” “Anything Goes,” and “Blow, Gabriel, Blow”—to Reno as played by Merman, a singer-actress of true star quality. As the curtain opens, Reno sings the first two of these songs to Billy, the man she supposedly loves, before he asks her to seduce Sir Evelyn so that Billy can successfully woo Hope. The degree to which Reno expresses her admiration for Billy in “I Get a Kick Out of You” and the mutual admiration expressed between Billy and Reno in “You’re the Top” might prompt some in the audience to ask why the creators of

Anything Goes

could not bring themselves to “make two lovers of friends.”

36

In

Anything Goes

Porter does not attempt the variety of musical and dramatic connections that will mark his relatively more integrated classic fourteen years later,

Kiss Me, Kate

(discussed in

chapter 10

). But Porter does pay attention to nuances in characterization and to the symbiotic relationship between music and words. To cite three examples, the sailor song, “There’ll Always Be a Lady Fair,” sounds appropriately like a sea chantey, the chorus of “Public Enemy No. 1” is a parodistic hymn of praise, and Moon’s song, “Be Like the Bluebird,” makes a credible pseudo-Australian folk song (at least for those unfamiliar with “authentic” Australian folk songs).

More significantly, Reno’s music, as befitting her persona, is rhythmically intricate, ubiquitously syncopated, and harmonically straightforward. It is also equally meaningful that in “You’re the Top” Billy adopts Reno’s musical language as his own but changes his tune and his personality when he sings the more lugubrious “All through the Night” with Hope. But even this song, dominated by descending half steps and long held notes, exhibits Reno’s influence with the syncopations on alternate measures in the A section of the chorus and especially in the release when Billy laments the daylight reality (Hope does not sing this portion). Billy’s syncopated reality partially supplants the long held notes: “When dawn comes to waken me, / You’re never there at all. / I know you’ve forsaken me / Till the shadows fall.”

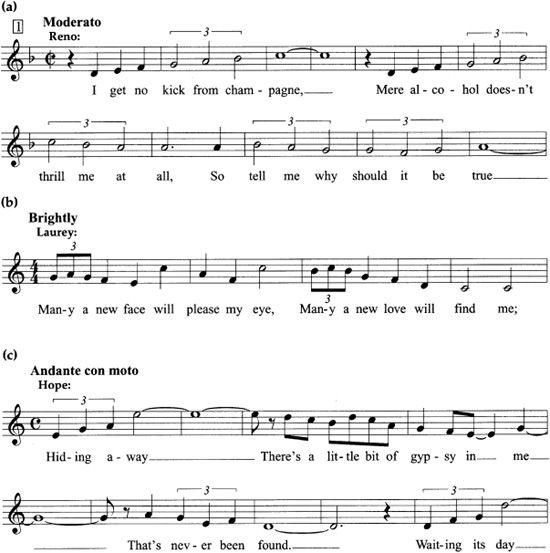

Although rarely faithfully executed in performance, Porter’s score also gives Reno an idiosyncratic and persistent rhythmic figure in “I Get a Kick

Out of You,” quarter-note triplets in the verse (“sad to

be

” and “leaves me total

ly

”) and half-note triplets in the chorus (“kick from cham-[pagne],” “[alco]-

hol

doesn’t thrill me at [

all

],” and “tell me why should it be”), the latter group shown in

Example 3.1a

. Because they occupy more than one beat, quarter-note and half-note triplets are generally perceived as more rhythmically disruptive than eighth-note triplets.

37

Consequently, Reno’s half-note triplets shown in

Example 3.1a

, like the quarter-note triplets that open the main chorus of Tony’s “Maria” (“I just met a girl named Maria” [

Example 13.2b

, p. 283]), are experienced as rhythmically out of phase with the prevailing duple framework. A good Broadway example of the conventional and nondisruptive eighth-note triplet rhythm (one beat for each triplet) can be observed at the beginning of every phrase in Laurey’s “Many a New Day” from

Oklahoma!

(

Example 3.1b

). Broadway composers have never to my knowledge articulated the intentionality or metaphoric meaning behind this practice. Nevertheless, with striking consistency, more than a few songs featured in this survey employ quarter-note and half-note triplets in duple meter (where triplets stretch in syncopated fashion over three beats instead of two) to musically depict characters who are temporarily or permanently removed from conventional social norms and expectations: Venus in

One Touch of Venus

, Julie Jordan in

Carousel

, Tony in

West Side Story

.

38

In

Guys and Dolls

, rhythms are employed or avoided to distinguish one character type from another. The tinhorn gamblers and Adelaide frequently use quarter-note triplets, while Sarah Brown and her Salvation Army cohorts do not.

Porter’s use of Reno’s rhythm in the chorus of “I Get a Kick Out of You” constitutes perhaps his most consistent attempt to create meaning from his musical language. Half-note triplets dominate Reno’s explication of all the things in life that do not give her a kick; they disappear when (with continued syncopation, however) she informs Billy that she does get a kick out of him. Reno will also sing her quarter-note triplets briefly in the release of “Blow, Gabriel, Blow” (not shown), when she is ready to fly higher and higher.

39

By the time Hope loses some of her inhibitions and finds the gypsy in herself (“Gypsy in Me”) in act II, she too will adopt this rhythmic figure on “hiding a-[way],” “never been,” and “waiting its” (

Example 3.1c

). By usurping Reno’s rhythm, Hope will become more like the former evangelist and, ironically, a more suitable partner for Billy.

40

Example 3.1.

Triplet rhythms

(a) “I Get a Kick Out of You” (

Anything Goes

)

(b) “Many a New Day” (

Oklahoma!

)

(c) “Gypsy in Me” (

Anything Goes

)

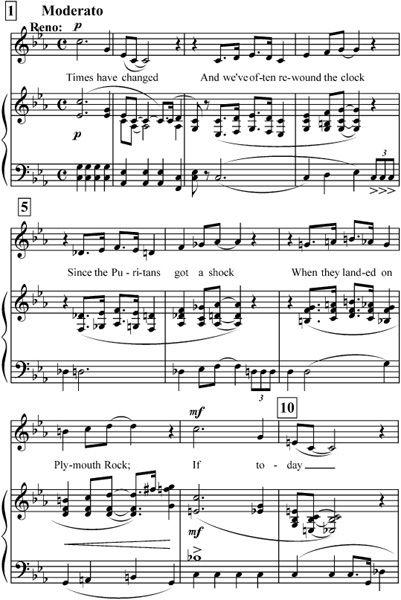

The verse of the title song shown in

Example 3.2

offers a striking example of Porter’s “word painting,” Kivy’s “textual realism” introduced in

chapter 1

. Even if a listener remains unconvinced that the gradually rising half-steps in the bass line between measures 3 and 7 (C-D -D) depict the winding and consequently faster ticking of a clock, Porter unmistakably captures the changing times in his title song. He does this by contrasting the descending C-minor arpeggiated triad (C-G-E

-D) depict the winding and consequently faster ticking of a clock, Porter unmistakably captures the changing times in his title song. He does this by contrasting the descending C-minor arpeggiated triad (C-G-E -C) that opens the song on the words “Times have changed” with a descending C-major arpeggiated triad (C-G-E-C) on the words “If today.”

-C) that opens the song on the words “Times have changed” with a descending C-major arpeggiated triad (C-G-E-C) on the words “If today.”

41

The topsy-turvy Depression-tinted world of 1934 is indeed different from the world of our Puritan ancestors. Porter makes this change known to us musically as well as in his text.

Example 3.2.

“Anything Goes” (verse, mm. 1-10)

In the chorus of “Anything Goes” Porter abandons “textual realism” in favor of a jazzy “opulent adornment” and does not attempt to convey nuances and distinctions between “olden days,” a time when “a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking,” and the present day when “anything goes.” Much has changed between 1934 and today and the chorus of “Anything Goes” remains one of the most memorable of its time or ours. Nevertheless, it is difficult to argue that this central portion of the song possesses (or attempts to convey) a dramatic equivalence with its text, even if it brilliantly captures an accepting attitude to a syncopated world “gone mad.” Similarly, in “You’re the Top” Porter does not capitalize on the text’s potential for realism and opts for inspired opulent adornment instead. Thus, although the “I” always appears in the bottom throughout most of the song, the “you” blithely moves back and forth from top to bottom.”

42

The upward leaping orchestral figure anticipates the word, “top,” but the sung line does not, and at the punch line, “But if Baby I’m the bottom, / You’re the top,” both Billy and Reno (“I’m” and “You’re”) share a melodic line at the top of their respective ranges.

43

In the end a search for an underlying theme in

Anything Goes

yields more fun than profundity. An Englishman is good-naturedly spoofed for speaking a quaint “foreign” language and for his slowness in understanding American vernacular, and the celebrity status of religious entertainers like Aimée Semple McPherson and public criminals like Baby Face Nelson are caricatured by evangelist-singer Reno Sweeney and Public Enemy No. 1 (Moon Face). On a somewhat deeper level, the music suggests that the friendship between Reno and Billy has more vitality and perhaps greater substance than the eventual romantic pairings of Billy and Hope and Reno and Sir Evelyn. Not only does Porter demonstrate their compatibility by having Billy and Reno share quarter- and half-note triplet rhythms, but he shows his affection for them by giving them his most memorable songs. By the end of

Anything Goes

some may wonder how a person who cannot even sing could deserve a gem like Reno who sings nothing but hits.