Enemy on the Euphrates (10 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

But now they were the enemy. The Bani Turuf had fallen under the spell of jihad and they would have to be punished. On the evening of 13 May 1915, the Anglo-Indian punitive column advanced towards Khafajiyya on both sides of the Karkha river with Wilson, mounted on an Arab mare, acting as guide. The assault on the village commenced with the artillery firing incendiary shells into the village, setting its reed huts alight and burning alive a number of horses and water buffalo

abandoned by their owners. In spite of the overwhelming force brought against them the Bani Turuf put up a strong resistance, replying to the artillery and machine-gun fire of the British and Indian troops with a fierce fusillade from their rusty Martini-Henry rifles.

The bombardment of Khafajiyya went on for three days. At the end 150 Arabs lay dead while most of the women and children had fled into the marshes. Only a few tribesmen remained holding out in the village’s small mud-brick fort. Wilson got close to the fort and tried to get its defenders to surrender but with no success. Finally, a company of the 76th Punjabis stormed it, bayoneting most of its dwindling band of survivors, Eleven prisoners were taken: short ragged men with long plaited hair, they sat on the ground surrounded by the Punjabis whose bayonets still dripped with the blood of their enemy. Wilson recognised one of them: it was Sheikh ‘Asi’s qahwaji. The coffee-maker looked up at Wilson.

O Wilson, why have you brought this on us? It is you who have led these men here. Was it for this that you ate our bread and wandered in our marshes and made maps? Treachery, treachery was in your heart and lies on your lips, and now the blood of our brothers is on your head. May God pardon you!

3

Reflecting on this episode many years later, Wilson admitted that ‘it was not without inward misery that I saw the blazing village and the dead bodies of the cheerful scoundrels whom I had known in earlier years … and I was witnessing the slaughter of men whom I had come to regard as friends.’

4

Wilson was not a heartless or brutal man: indeed, his obsession with ‘order’ partly reflected his belief that it was the ‘poor and humble’ who suffered most from the kind of disorder he had witnessed during the periods of civil war and economic chaos in Persia. He comforted himself with the knowledge that once hostilities in Iraq had ended, men like himself, the ‘politicals’ in the service of the government of India, would have an opportunity to demonstrate to such ‘cheerful scoundrels’ that while ‘order’ and obedience to the representatives of the British Empire would certainly be required of them, in return they would receive security, progress and prosperity.

In the meantime, the lesson taught to the erring Bani Turuf was having a salutary effect not only upon the remaining warlike tribes of Persian Arabistan but also on the potentially hostile Marsh Arabs on the Iraqi side of the border. The rice-growing Al Bu Muhammad tribe on the Tigris below ‘Amara could hear the fearsome artillery barrages which Gorringe’s force laid down upon Khafajiyya and soon learned from fleeing Bani Turuf of the overwhelming force which the British were now prepared to unleash on any who opposed them.

After the successful punitive expedition into Persian Arabistan, Major General Gorringe learned that the town of ‘Amara on the Tigris had been captured on 2 June by an amphibious force under General Townshend and he was ordered to dispatch three battalions, a cavalry regiment and a field battery there, sending the remainder of his force back to Ahwaz to protect the oilfield. Wilson accompanied the patrol heading for ‘Amara, acting as a guide for the advancing column stretching out several miles, marching along the northern edge of one of the world’s most extensive marshes, through territory invested by potentially hostile Arab tribes. Wilson visited their camps accompanied by a handful of Indian troopers, often at great personal risk, taking coffee with their sheikhs, giving assurances and warnings. After reaching ‘Amara on 14 June, Wilson was ordered to return to Basra, where for a few days he was plunged back into the routine of office work; but on 23 June Gorringe asked him to rejoin his staff and he set off up the Tigris by launch.

Gorringe had now been ordered to swing his division to the west to capture Nasiriyya on the Euphrates, crossing Lake Hammar accompanied by a formidable flotilla of gunboats and armoured launches, negotiating its way through treacherous marshes and unmapped canals. Once again, Wilson scouted for the expedition, often up to his neck in muddy water, shot at by Arab and Turkish snipers, searching out weak points in the enemy lines and suitable routes for the passage of Gorringe’s amphibious column. After eventually reaching the outskirts of Nasiriyya with a force depleted by heatstroke and disease, a fierce and bloody action took place on 22 June 1915 in which Gorringe’s force of 4,600 infantry and twenty-six naval and field guns completely overwhelmed a Turkish force of

almost equal size supported by a host of Arab auxiliaries. Wilson was in the thick of the fighting in spite of the fact that he was now suffering from a raging fever. The town was entered on the 25th and Wilson was immediately appointed assistant to its military governor. Sometime later Gorringe’s chief of staff told him, ‘You are damned lucky to have survived; a good many of us were expecting each evening to be your last.’ Wilson also learned that he had been recommended for the DSO or MC, either of them unusual for a PO. In the event he received the DSO.

While the capture of Nasiriyya and the virtual elimination of Turkish and Arab forces in the vilayet of Basra signified a major success for the Anglo-Indian invasion force, the operations of the remainder of Gorringe’s forces in Persian Arabistan also ensured the success of what had been the primary objective of the invasion. By June 1915, the pipeline from Ahwaz to Abadan was fully repaired. Never again would Anglo-Persian’s oil production operations be threatened by hostile forces during the war. In spite of the disruption caused by Arab raiders in early 1915, output rapidly recovered during the remainder of that year resulting in a total annual production of 3.8 million barrels – around 10,000 barrels per day, a 25 per cent increase over the previous year. By 1916, this had increased to nearly 13,000 barrels and by 1918 – the end of hostilities on the Western Front – Anglo-Persian’s refinery at Abadan was processing nearly 25,000 barrels per day.

5

And although the company’s operations only provided around a fifth of the Royal Navy’s requirements, as the French prime minister Clemenceau put it to President Woodrow Wilson, ‘Every drop of oil secured to us saves a drop of human blood.’

6

Imperial Objectives in the East

On Monday 12 April 1915, Sir Mark Sykes took his usual early morning stroll from his four-storey town house in Buckingham Gate to Westminster Cathedral, where he heard Mass, and then returned home for breakfast. No. 9 Buckingham Gate had not been his first choice as a London base for his parliamentary work. Having inherited his father’s huge estate in 1913, valued conservatively at £290,000, he had originally considered renting a furnished house in Mayfair at £1,200 per year; but his wife Edith had put her foot down at this extravagance and, in the end, Sykes had to agree that the Buckingham Gate house at £500 per year was not only much more economical but was ideally placed for his work as an MP. And since his recent appointment by Kitchener to the War Office, Buckingham Gate was eminently suitable – a short walk through St James’s Park took him to Whitehall and Horse Guards Parade. But on this particular day he was heading for the Foreign Office, and at 11.00 a.m. Sykes strode purposefully into the designated committee room carrying a large briefcase packed with notebooks, diaries, maps, gazetteers, travel brochures and photographs and settled into one of the comfortable chairs surrounding the huge table in the centre of the room.

The committee to which Kitchener had dispatched Sykes as his personal representative had been established by the prime minister, Herbert Asquith, charged with advising the cabinet on ‘British Desiderata in Turkey-in-Asia’: in effect, what to do with the vast non-European territories of the Ottoman Empire once it had been defeated;

and at that particular moment, few Englishmen had any doubts about the rapid defeat of ‘the Turk’.

Indeed, ‘the Turk’ already seemed to be on the brink of defeat. In December 1914 an Ottoman army of 90,000 had advanced into the Caucasus, initially causing widespread panic among its Russian defenders. In early January 1915, in a raging blizzard and with temperatures dropping to minus 30°f, they had thrown themselves against the Russian army defending the town of Sarikamish. But the plan had not taken account of the atrocious weather conditions and in an attempt to outflank the Russians, Enver Pasha’s troops had floundered in the snowdrifts and over 30,000 men froze to death. Most of the survivors were forced to surrender and only 12,000 of the initial attacking force escaped the catastrophe.

Also in January 1915, Djemal Pasha; commanding the Ottoman Fourth Army based at Damascus, had sent 20,000 men of the VIII Corps, including the Arab 25th Division, to attack British forces defending Egypt’s eastern frontier. After a ten-night march across the Sinai peninsula, they had mounted attacks against British posts at Qantara in the north and Kubri, seven miles north of Suez, in the south. According to Djemal Pasha, ‘The Arab fighters who constituted the bulk of the 25th … performed splendidly.’

1

Djemal Pasha had hoped that the success of an Ottoman force would trigger an Egyptian Muslim uprising. On 3 February his troops mounted a major attack at Tussum at the southern end of Lake Timsah, six miles south-east of Ismailia. But it was another disaster; they simply did not have sufficient strength to make a breakthrough. The few Ottoman troops who succeeded in crossing the Suez Canal were all killed or captured and Djemal Pasha was forced to order a retreat to Beersheba, having lost about 1,400 men.

Meanwhile, the government of India had successfully established a bridgehead in Southern Iraq, captured Basra and Qurna and were currently taking steps to defend the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s facilities in south-west Persia. Reinforcements were arriving daily from India and it could only be a matter of time before an advance further up the Tigris commenced.

True, the recent naval assault on the Dardanelles had been disappointing. Between 19 February and 13 March Vice-Admiral Sackville Carden had attacked the forts at the mouth of the Dardanelles and attempted to sweep the mines which the Turks had laid further up the straits. But heavy gunfire from the Turkish forts, gun emplacements and 6-inch mobile howitzers on the northern, peninsular side of the channel had made it impossible for his minesweepers to carry out their task. Overwhelmed by the difficulties of trying to force a way through, Admiral Carden had a nervous breakdown and was replaced by his second in command, de Roebeck. On 18 March Admiral de Roebeck, under strong pressure from Winston Churchill to demonstrate progress, began a major naval advance into the straits. Unfortunately, a number of capital ships,

Irresistible

,

Inflexible

and

Ocean

, and the French battleships

Bouvet

and

Gaulois

were sunk by mines or seriously damaged by coastal shellfire and de Roebeck was obliged to call off a plan to force his way through to Istanbul. However, a formidable land army under General Sir Ian Hamilton was now being assembled at Mudros on the Aegean island of Lemnos and there was a strong expectation that within a few days a major amphibious assault on the Gallipoli peninsula would be mounted. Then the combined naval and land forces would sweep through to the Ottoman capital.

The committee to which Sykes had been summoned was to be chaired by Sir Maurice De Bunsen, formerly British ambassador in Vienna, who had brought together representatives of all the government departments whose views would have to be taken into account in putting together the committee’s final report: the War Office, the Admiralty, the India Office, the Board of Trade and of course, the Foreign Office itself. As Sykes glanced around the table he would have seen a group of elderly men – in their sixties or older – with only two exceptions. There was George Clerk of the Foreign Office, whom Sykes had met once or twice and who was in his mid-thirties, and sitting to the left of the chairman was a very short bald man whom Sir Maurice introduced as ‘Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence’. As yet Sykes knew him only by reputation.

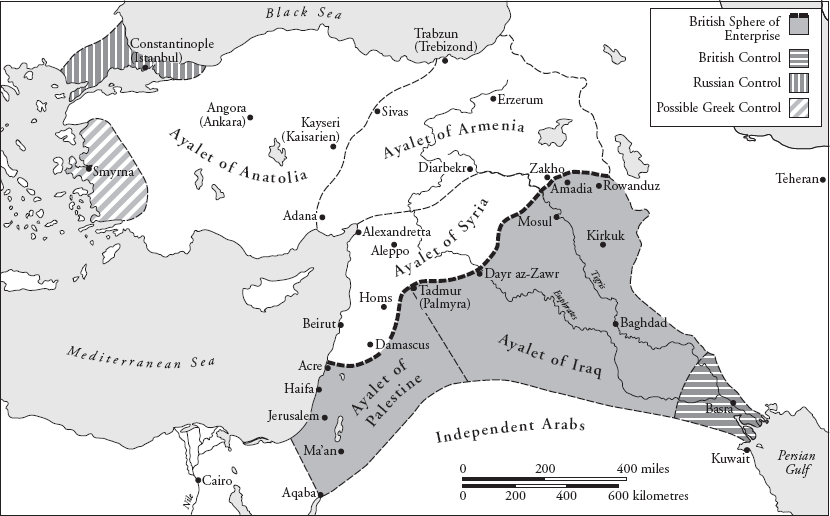

SYKES’S 1915 PROPOSED SCHEME FOR THE ‘DECENTRALISATION’ OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE’S EASTERN POSSESSIONS

Calling the meeting to order, Sir Maurice reminded the assembled officials of their remit. The cabinet had already agreed to the tsar’s demand for Istanbul and the Turkish Straits together with the islands of Imbros and Tenedos in the northern Aegean, and in return the tsar’s government had assured Britain that it would respect the ‘special interests’ of Britain and France in Asiatic Turkey. Sir Maurice made it clear from the start that the ‘special interests’ they were being asked to define were ‘the primary economic and commercial interests of Great Britain and the policy it would be desirable for H.M. Government to adopt to secure those ends’.

2

Doubtless Britain also had a ‘civilising mission’ east of the Dardanelles and eventually the ‘white man’s burden’ would have to be taken up; but for the moment it was ‘economic and commercial interests’ which were the overriding focus of the committee’s deliberations. Accordingly, the first civil servant called upon by Sir Maurice to address the committee was Sir Hubert Llewellyn Smith, permanent secretary of the Board of Trade.