Enemy on the Euphrates (43 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

At this point the river was only forty yards wide but fast-flowing and in places as much as ten feet deep. Nevertheless Captain Moore, with the company jemadar, Panchalal Limbu, led several desperate attempts to cross the river under heavy fire from the insurgents’ positions. None succeeded and during one of these gallant efforts both men were killed. So as darkness fell, Coningham was forced to withdraw both companies of Gurkhas to a position 500 yards from the river.

Once again, it appeared that it might be impossible to relieve Rumaytha. The column’s advance was blocked. Worse still, as the British attacks petered out, the Arabs began to go on the offensive, mounting sporadic attacks on the 45th Sikhs holding the British forward positions. The situation of the second relief column was now as precarious as that of its predecessor. There was no possibility of further reinforcements yet Coningham remained, facing a strong and resolute enemy in possession of an equally strong defensive position. His men and horses were running short of water and he had insufficient ammunition for a full second day’s fighting. There were also a substantial number of sick and wounded with only very basic medical supplies available. He had little choice except to order one more attack.

At dawn the next day, the 10th Gurkhas were again thrown against the right flank of the enemy’s position. Two platoons of Gurkhas from ‘C’ Company, the water reaching up to their armpits – but this time, supported by covering fire from artillery, Lewis and Hotchkiss guns – managed to cross to the left bank of the river on a front of 500 yards. Taken in the flank, the insurgents fell back and the Gurkhas began to advance down the left bank of the Hilla, rolling up the enemy’s position. Coningham now ordered the 45th Sikhs to mount another frontal attack on the rebel position on the right bank, but as they advanced they found the enemy trenches abandoned. The rebels had slipped away –

either to avoid being outflanked or because of a shortage of ammunition. So by 6.45 a.m. on 20 July Coningham had three battalions of infantry occupying the insurgents’ former position, and two hours later a train from Diwaniyya arrived, bringing water, ammunition and medical dressings which Coningham had ordered to be loaded during the night.

Leaving the 116th Mahrattas to guard the train and transport vehicles, Coningham moved forward without opposition. By 3.45 p.m. word came through that his advance guard of cavalry had entered Rumaytha thirty-five minutes earlier. Rumaytha had been relieved, but at the cost of three British officers and thirty-two Indian other ranks killed and two British officers and 150 Indian other ranks wounded. In addition, since Rumaytha had been first besieged, the garrison had suffered 148 casualties killed, wounded or missing.

23

Even then, the tribulations of the garrison and relief force were not over. Leslie knew it was folly to continue to leave small numbers of men defending each and every town in insurgent territory and he therefore ordered Coningham to retire with all his men and guns to Diwaniyya. So on the morning of 22 July the column set off northwards. It was not long before bands of Arab horsemen began to appear at the rear and on the flanks of the column. Then, at 7.00 a.m., under cover of a dust storm, a large party of tribesmen fell upon the 87th Punjabis who were acting as rearguard.

24

The 45th Sikhs were ordered to turn about and support the 87th, but as they did so they became hopelessly intermingled with the cavalry who were also trying to come to the aid of the infantry. RUMCOL was now in great danger, especially since its commander could see nothing but dust, and during a chaotic few minutes the 87th Punjabis suffered sixty-nine casualties including two of their British officers.

25

Fortunately, three companies of the Royal Irish Rifles managed to make their way to the rear of the column and eventually succeeded in driving off the insurgents and re-forming the rearguard.

Thereafter, the rebels contented themselves with occasional sniping, with their horsemen ranging round the column but never closing in. At 5.00 p.m. the column was able to halt and make a protected camp alongside the river bank. The column’s exploits on 22 July had rivalled its

earlier achievements. Having started out at 3.00 a.m. they had marched and fought through the fierce heat of the day, made worse by a dust storm which had raged for several hours. By the time they made camp, both British and Indian officers and men were very nearly at the end of their endurance. Fortunately, after this, Coningham was able to continue his withdrawal to Diwaniyya in relative safety, arriving there on 25 July.

However, the general military situation remained far from satisfactory. The insurgents had been left in control of Rumaytha, the uprising had spread to neighbouring tribes and word was spreading rapidly throughout all the tribes of the Middle and Lower Euphrates that the

Ingliz

had been defeated, that they were too weak to withstand the rebel forces and that they were clearly in the process of relinquishing control over the country.

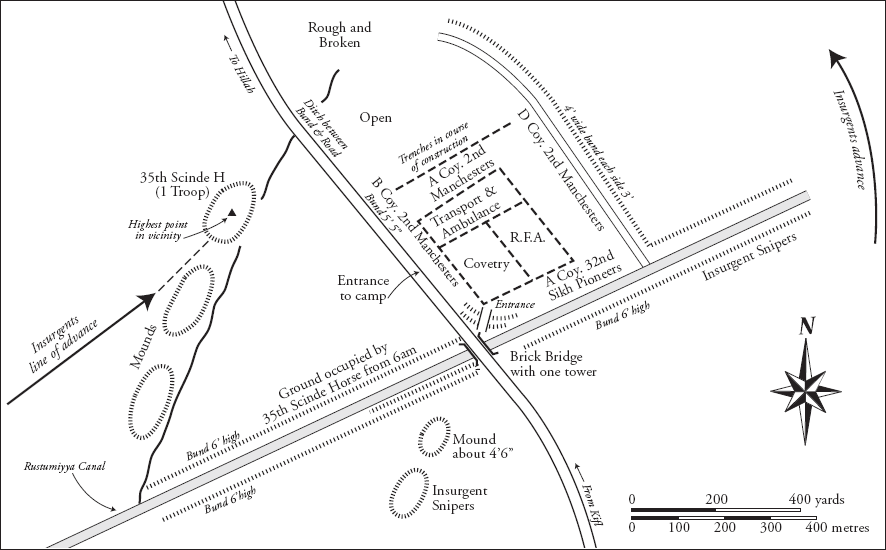

THE SCENE OF THE MANCHESTER COLUMN DISASTER JULY 1920: THE CAMP ON THE RUSTUMIYYA CANAL

The Destruction of the Manchester Column

While General Haldane’s attention was focused on the besieged garrison at Rumaytha, the insurgency continued to spread, gathering in more and more tribesmen, their sheikhs swept up in a great swell of religious fervour and primitive patriotism which gave them little room to manoeuvre, even when their sheikhly interests might have been better served by remaining obedient to the British. By mid-July 1920 around 35,000 Arab tribesmen were in arms and the number of British garrisons and outposts at risk of being cut off and destroyed was increasing.

1

In particular, fears grew for the safety of the British outpost at Kufa, where a small detachment of Indian troops from the 108th Infantry Regiment was keeping a wary eye on the rebellious city of Najaf seven and a half miles to the south-west. Kufa, a town of around 3,500 inhabitants, situated on the right bank of the channel of the same name, lay thirty-three miles south of the British base at Hilla. For twenty-one miles of that distance a narrow-gauge railway, built during the war, ran as far as Kifl, another small British outpost and railway terminus and the point where the Hindiyya branch of the great Euphrates divides, forming two further channels, the Kufa and the Shamiyya. As early as 11 July, the stationmaster at Kifl had reported that attacks on the railway station and telegraph lines were anticipated and the railway staff were authorised to withdraw north to Hilla. However, the following day, the PO for the Hilla Division, Major Pulley, considered it safe enough for the railway staff to return.

Meanwhile, Major P. Fitzgerald Norbury, the PO for the Shamiyya Division, accompanied by his youthful APO, Captain Mann, began a series of visits to the sheikhs of the Khaza’il, Bani Hasan and Shibl tribes, attempting to bribe them to abandon the al-Fatla, who were currently the most actively engaged insurgents. But this was to no avail and on 13 July the al-Fatla and their allies began to threaten Kufa.

The defenders of Kufa totalled 730 men, 486 of whom were Indian troops of the 108th Infantry plus their four British officers.

2

The only other fighting men were a motley force of 115 Arab and Persian levies commanded by six British officers and three British NCOs. There were also 102 Indians and fourteen British employed by the Civil Administration. However, Norbury had selected a strong defensive position of stone buildings on the edge of the town and adjacent to the river and ensured that this strongpoint was well stocked with supplies and ammunition. Moreover the gunboat HMS

Firefly

had just arrived at Abu Sukhair, a few miles south of Kufa, having steamed down from the Upper Euphrates, and could easily return to Kufa in a few hours.

Signs of hostility began to show themselves on 14 July when insurgents opened fire on a British launch carrying supplies which would have certainly been captured without the intervention of

Firefly

, after which the gunboat was ordered upriver to Kufa. Then, on 20 July, the British base in the town came under sporadic rifle fire.

By the following day the British outpost was completely encircled and the attacks grew fiercer. Soon a number of buildings near to the British defensive perimeter were set on fire and Norbury and Mann repeatedly led fire-fighting parties to try to extinguish the flames. On 22 July, in the course of another of these sorties, Captain Mann was shot and killed by the Arab attackers.

3

Wilson had lost yet another of his ‘young men’. Meanwhile, insurgent raiding parties began to threaten Kifl and on 23 July its railway station was overrun by a section of the Bani Hasan tribe, and the railway staff, who had been ordered back to their posts on 12 July, were captured and taken prisoner to Najaf.

As the military situation in the Shamiyya Division deteriorated, on Thursday 22 July Major General Leslie, still at Diwaniyya, was

summoned to Baghdad for a conference with the GOC-in-chief and the following day was flown up to Baghdad for the meeting with Haldane. Afterwards he paid a visit to his own 17th Division HQ and it was there, later that Friday morning, that he received a telegram from Colonel R.C.W. Lukin, commanding officer at Hilla, who had replaced the ‘hysterical’ General Wauchope a few days earlier. With Kifl overrun by rebel tribesmen and the Hilla–Kifl railway cut in a number of places, Colonel Lukin informed Leslie that he was under intense pressure from the local PO, Major Pulley, to send out a detachment towards Kifl, in order to ‘show the flag’ in the hope that this would deter the ‘wavering’ northern sections of the Bani Hasan from joining the insurgency.

4

The telegram requested authorisation to do so.

The only troops at Hilla available for this purpose were the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment (less one company), a field artillery battery, a field ambulance section, a company of Indian pioneers and two squadrons of Indian cavalry, in total around 800 men, all units from the 18th Division which had been sent to Hilla, on GHQ’s order, to form a column there for the purpose of retaking Kifl and relieving Kufa – but only when a sufficiently strong force had been assembled.

Colonel Lukin’s telegram informed Leslie that he intended to send a column made up of the units currently available down the road to Kifl to a point six miles south of Hilla called Imam Bakr, which had been reconnoitred and was reported as having a good supply of water for both animals and men.

5

The objective was to ‘show the flag’ as requested by the PO. Lukin asked Leslie to approve this move and to authorise a continuation of the advance towards Kifl if circumstances allowed.

6

Leslie, who by now was fully aware of his commanding officer’s strictures about sending out under-strength columns at the behest of POs, decided to pass the request to the GOC-in-chief himself, so he telephoned GHQ and, in the presence of his own two staff officers, he read out Colonel Lukin’s telegram to Brigadier General Stewart, Haldane’s general staff officer who had taken the call. A few minutes later, Stewart replied, giving GHQ’s permission for the Manchester Regiment and other units to advance towards Kifl but, for the time

being, to go no further than Imam Bakr, which was to be considered ‘an outpost of Hilla’. The commander of the column was also ordered to avoid becoming engaged with superior hostile forces. Leslie then transmitted these instructions to Lukin at Hilla, sending a copy of his telegram by special dispatch rider to GHQ, and later that day he boarded an aircraft at Baghdad to fly back to Diwaniyya.

Precisely why General Haldane authorised the Manchester Column’s movement to Imam Bakr is something of a mystery. It was completely inconsistent with his previously stated objections to making an ‘unready push’ and the manoeuvre had no clear objective. Certainly, there was no reason why GHQ should defer to the judgement of the PO who had been pressing for the column’s dispatch. One possible explanation is that Haldane was expecting the arrival at Hilla of some of the units from the Rumaytha relief column he was planning to withdraw north from Diwaniyya and which could then be sent on immediately to reinforce the Manchesters at Imam Bakr. It was this more substantial force which would then advance further towards Kifl and Kufa.

However, when the Manchester Column was sent out on the afternoon of 23 July, neither Colonel Lukin at Hilla nor the officer commanding the column, Colonel Hardcastle, had any idea that reinforcements were en route to them and might be arriving shortly, a communications failure that was to have tragic results.

To better understand the course of events which was now about to unfold, let us first examine the terrain through which the column was to move. Between Hilla and Kifl the landscape was almost entirely flat and featureless except for the ruined Babylonian tower of Birs Nimrud – locally reputed to be the Tower of Babel – which would have been just visible, situated on a mound, about ten miles south-west of the column’s point of departure. At that time of year the terrain itself was a mixture of grey-brown desert covered with scrubby ‘camel thorn’ bushes intersected by a number of half-empty canals which fed off the Hilla branch of the Euphrates. Where these irrigation canals watered the land, rice fields – some of them quite extensive – broke the monotonous vista. Two of these irrigation canals, the Amariyya and the Nahr Shah,

ran roughly north–south, to the east of the road and the 2’6” railway line from Hilla, while two smaller canals, the Mashtadiyya and the Rustumiyya lay broadly east–west. Imam Bakr – the position six miles south of Hilla where Colonel Hardcastle had been ordered to halt, make camp and water the cavalry and transport teams from local wells – was a short distance north of the point where the road and railway line crossed the Mashtadiyya canal. As to the ‘road’ to Kifl along which the column would march – it was little more than an unmetalled track.