Enemy on the Euphrates (47 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

Firefly

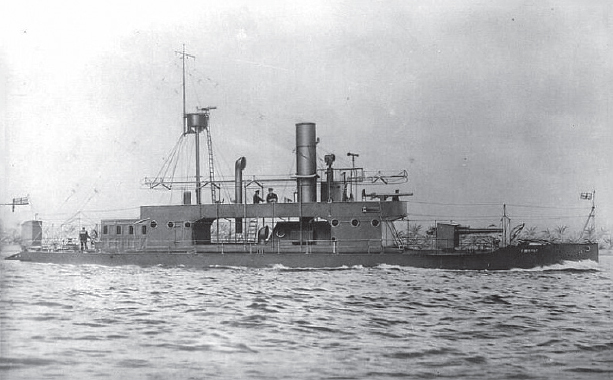

and her sister ships were powered by a single oil-fired 175hp engine which gave her a top speed of around nine and half knots. But the gunboats had three main defects. Firstly, their extremely shallow draught made them almost impossible to navigate in strong winds and on the Euphrates they were unable to manoeuvre at all – they could only steam ahead or astern.

4

Secondly, for some reason, in early 1915 the Admiralty had been under the impression that the gunboats’ prospective adversaries would only be lightly armed Arab irregulars, not disciplined regular troops with heavy weapons; consequently, the vessels were only provided with armour sufficient to withstand rifle fire. And thirdly, since they had only one boiler, were this to be put out of action for any reason – as indeed might be case if they met up with an enemy equipped with heavy arms – a hit on the boiler by shellfire would leave the ship absolutely helpless.

5

The gunboat HMS

Firefly

, one of the ‘Fly Class’ gunboats used against the insurgents

Indeed,

Firefly

herself had been smashed up by Turkish artillery in December 1916 during the retreat of ‘Townshend’s Regatta’ following the battle of Ctesiphon, after which she was captured by the Turks and used to considerable effect. However, she was later recaptured by the British during General Maude’s successful counter-attack the following year. So, since the British believed that the insurgents of 1920 had neither the heavy guns nor the military knowledge and experience to use them, news of the arrival of

Firefly

at Kufa in mid-July was received with great relief and jubilation.

Meanwhile, far to the south, another gunboat of the same class, HMS

Greenfly

, under the command of Captain Alfred C. Hedger, had already set off upriver from its base at Nasiriyya with orders to patrol the Euphrates north and south of Samawa. On 5 July, accompanied by another defence vessel,

F10

, she arrived at Samawa itself.

6

For the next month

Greenfly

and her consort steamed up and down the muddy river, returning fire upon any insurgents who had the temerity to challenge them and dealing out death and destruction to the reed huts of the rebels’ riverine villages. However, on 10 August, while heading downriver to help defend the town and railway station of Khidhr,

Greenfly

ran aground at a point five miles above its destination.

Had the Hindiyya Barrage still been under British control,

Greenfly

might have been floated off by closing the Hilla channel and directing all the water of the Euphrates down the Hindiyya branch. But the barrage was now in rebel hands. To make matters worse, this was the season of the year when the Euphrates water level was steadily falling. Over the next few days intense efforts were made to pull

Greenfly

off the sandbank. On 15 August, a second gunboat, HMS

Greyfly

, and another lightly armoured launch,

F11

, joined in the struggle to free her, coming under intense enemy fire while doing so and suffering numerous casualties from tribesmen firing from concealed positions on the river bank. On the 20th another effort was made. On that day

Greyfly

, accompanied by two launches, each carrying a company of Indian troops, managed to reach the

Greenfly

and to their surprise found that the insurgents had withdrawn. For the next two days strenuous endeavours were made to free

Greenfly

from the sandbank, but the mud had now closed further upon her with a vice-like grip. In the end, the little flotilla of rescuers had to admit defeat and set off back downriver to Nasiriyya.

7

The British had no wish to see

Greenfly

captured by the insurgents so there were now only two options open to them: abandon and scuttle the gunship or leave the crew on board, well equipped with rations and ammunition, ready for a second major rescue attempt as and when the necessary ships and special equipment could be assembled. Eventually the decision was taken to leave the crew on board; it was a decision which was later to have particularly tragic consequences.

One of the reasons against scuttling

Greenfly

was that, only a few days earlier, the British defenders of Kufa had themselves reluctantly decided to send one of

Greenfly

’s sister ships to the bottom. And this was not an action anyone wanted to repeat, if at all possible.

After arriving at Kufa in mid-July, HMS

Firefly

had tied up alongside a small redoubt, part of the British defensive position on the right bank of the river, and remained at that station guarding the approaches to the town from the east. On the opposite side of the river were dense palm groves and once the encirclement and siege of

the town commenced, the gunboat began to receive sporadic rifle fire from groups of insurgents occupying them. Returning fire with its much heavier weapons,

Firefly

soon discouraged these sharp-shooters and for a time fighting at this point subsided.

Then, on the morning of 17 August, the gunboat was suddenly subjected to heavy shellfire from the other side of the river and in a few minutes, during which a British soldier on board was killed and another badly wounded, the ship was set ablaze. After a further battering of shells,

Firefly

’s commander, Lieutenant D.H. Stanley, was fatally wounded and the remainder of the crew had to be taken off.

To Kufa’s garrison, the attack came as a terrible surprise. How had the despised ‘Budoos’ managed to field such heavy weapons against them? For many of the defenders it could only mean they were once again at war with the Turks. What they didn’t know was that the shells which were crippling the

Firefly

were fired by the 18-pounder British gun, captured by the rebels during the defeat of the Manchester Column. Haldane and his staff were well aware that this powerful field gun had been lost on the Kifl road; but they were fairly sanguine about it because, a few minutes before its capture, one of the British gunners had managed to remove the breechblock. What the British did not appreciate was that the small number of experienced former Ottoman army officers and NCOs fighting in the insurgent ranks had managed to forge a replacement for the missing part and bring the gun back into service.

As the fire on board the

Firefly

raged from stem to stern, the British and Indian defenders, cooped up within the perimeter of their strongpoint along the right bank of the Kufa channel, realised that the ship’s magazine would soon explode, seriously damaging the redoubt and neighbouring positions along the river bank and possibly devastating their occupants. Since they had no wish to abandon those positions the decision was taken, very reluctantly, to scuttle

Firefly.

So several Lewis guns were brought up and the gunboat’s plates were swiftly perforated by heavy fire. Within minutes the little gunship tilted to one side and then settled down on the silty bottom of the Hindiyya channel, where she would remain for the duration of the campaign.

While General Haldane’s attention was focused primarily on the precarious situation of the troops retiring from Diwaniyya to Hilla, he remained anxious about the fate of the capital. The wholly inadequate size of its garrison and the increasingly truculent attitude of the local Muslim population meant that for a time he was compelled to resort to rather crude ruses – such as marching the same units backwards and forwards across the city – to try to give the impression that the garrison was considerably larger than it actually was. Haldane also began the construction of a number of defensive earthworks around the city’s perimeter, which were later to be replaced by high, brick-built blockhouses.

Meanwhile, further bad news arrived. The insurrection was no longer confined to the central and southern Euphrates but had spread northwest, where the ‘Azza and other smaller tribes on the Diyala river had joined the revolt.

For some time the Euphrates rebels had been sending out emissaries all over Iraq to try to win the support of the other tribes. In late July a sayyid named Sa’id Sara al-‘Azawi reached the ‘Azza, whose tribesmen inhabited the lands along the Khalis canal, north-east of the orange-growing town of Ba’quba. Ba’quba itself was the principal town of the Diyala Division, situated on the left bank of the river of the same name, thirty-four miles north-east of the capital. The news that Sayyid Sa’id brought was that the uprising which had begun in the mid-Euphrates was spreading north and south while everywhere the British were retreating from their main strongpoints. He urged the ‘Azza to join the uprising.

8

The paramount sheikh of the ‘Azza was the twenty-five-year-old Sheikh Habib al-Khayizran and although he listened respectfully to the sayyid’s exhortations, for the time being he held back from committing himself and his tribe to what would clearly be an extremely dangerous venture. However, a few days later, some travellers on the main road to Ba’quba were attacked and pillaged in what was probably a simple act of banditry; but this was not how the local PO, Major Hiles, saw it. Fearing an imminent outbreak of the kind which had occurred on the Euphrates, he immediately called up police and military from Baghdad. On their arrival, Hiles sent out orders to the sheikhs of all the tribes in

the Ba’quba Division, including Sheikh Habib, to assemble in the centre of Ba’quba town on the pretext that he wished to obtain further information about the robbery. Once they had all arrived, Hiles had them all arrested. The assembled sheikhs were then lectured on the mandate and the requirement that they must on no account have anything to do with the insurgents or try to get in contact with them. Some days later the sheikhs were released – all but Sheikh Habib – who for some reason had attracted the attention of Major Hiles.

Years later, Sheikh Habib gave the following testimony of the attempt by Major Hiles to win him over to the pro-British camp.

After some days, Major Hiles summoned me and said, ‘You’re an intelligent man; you know very well the military forces which are at the disposal of the British Government and the power with which it can ruthlessly crush its enemies. Those Iraqis who have rebelled against it including the leaders of the tribes will, in the end, be exterminated. However I like you and I’m concerned about you; I don’t want you to fall into a trap; I’m seeking a happy outcome for you. If you follow my advice, without doubt you will be viewed by Great Britain as one of the great men of Iraq. Moreover the government has ordered me to give you 40,000 rupees for you to spend as you wish and is ready to double that when you want it.’

9

To which Sheikh Habib replied with the following forthright reply: ‘Truly, I am in need of such a sum of money; but I am not going to sell my honour for it.’

10

For the time being, there the matter rested and, fortunately for Sheikh Habib, after a few days Major Hiles fell ill and returned to Baghdad for treatment, after which he was replaced by a Captain Lloyd, political officer for Daltawa, a town ten miles west of Ba’quba. The sheikh now told Lloyd that he too was ill and needed to visit Baghdad to see his own physician. Lloyd eventually agreed to his request and Sheikh Habib set off for the capital. However, on his arrival he went straight to the ‘People’s School’ where the Haras al-Istiqlal had one of its main political bases. There, ‘Ali Bazirgan, the school’s director, confirmed the information about the insurgency on the Euphrates and gave him further news of the most recent

defeats and withdrawals suffered by the British. Bazirgan also told the sheikh that Taqi al-Shirazi, the Grand Mujtahid, had issued a statement urging the unity of all Muslims and that the leadership of Haras al-Istiqlal considered the Diyala region critical for the uprising, since if the tribes there joined the insurgency, it would cut the road and rail link to Persia along which the British were trying to get reinforcements.

‘In due course, I set off back to Daltawa’, Sheikh Habib later recalled.

There, I made contact with a number of tribal leaders, the foremost of whom were Sheikh Hamid al-Hasan of the Bani Tamim tribe and Sheikh Mukhbir bin Murhaj bin Karim, of the Karkhiya. I related to them what I had heard from the leadership in Baghdad and I asked them to come out in support of the uprising on the Euphrates and its leaders. I also asked each of them to swear an oath on the Qur’an that they would keep their promises and commitment to building a Muslim Arab Government.

11

On 9 August, the Karkhiya kept their word: they began the revolt on the Diyala by cutting the railway line from Baghdad to Quraitu near the town of Ba’quba and thereby severing all rail communications with Persia.

12

The following morning, the first reinforcements from India, the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Rajputs, arrived in the capital. So later that day, Haldane gave orders for a mixed column under the command of Brigadier General H.G. Young, commander of the 7th Cavalry Brigade, to ‘nip in the bud’ – as Haldane later described it – the unwelcome and hitherto unexpected extension of the uprising to the Diyala. However, Haldane was still anxious about the safety and security of Baghdad and was reluctant to send troops away from the capital at a time when events seemed to presage a growing threat to the city. Indeed, had it not been for the timely arrival of the 7th Rajputs, he would probably have felt obliged to ignore the problems on the Diyala altogether until he had a much stronger force with which to deal with them.