Enemy on the Euphrates (38 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

After further casualties at the hands of the growing number of insurgents, the khans were abandoned and all troops and civilians

brought into the serai, the defensive perimeter of which formed a walled rectangle around the main building, about 150 by 75 yards. The rebels were left in complete control of the remainder of the town and by the following day the Rumaytha serai was surrounded by rebel trenches and completely under siege.

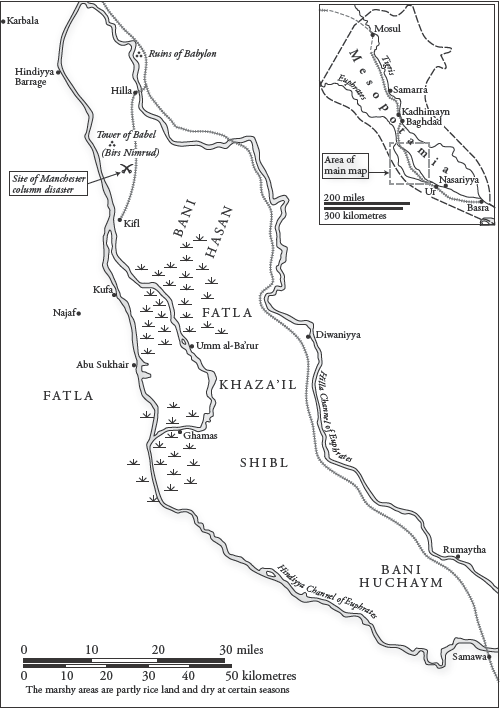

It was just the beginning. In a little over a month the number of insurgents on the Middle and Lower Euphrates would swell to over 100,000; British forces would be compelled to withdraw from every town and village except Hilla, Kufa and the British base outside Samawa, which were all surrounded and besieged; by mid-August Wilson’s administration in the region would completely collapse and revolutionary governments would be set up in the cities of Karbela’ and Najaf. The great Arab Revolt – the inevitable outcome of Britain’s incoherent policy in the region since 1918 – had begun.

THE MIDDLE EUPHRATES REGION, EPICENTRE OF THE 1920 REVOLUTION, SHOWING THE PRINCIPAL TRIBAL AREAS

Discord and Disputation

Having unwillingly returned to Baghdad from his Persian ‘hill station’ at Karind on 19 June 1920, General Haldane once again began to contemplate escaping Iraq’s summer heat, a torment that was becoming daily more and more unbearable to the GOC-in-chief. Indeed, he made no secret of the fact that he ‘disliked the idea of remaining in Baghdad throughout the hot weather, where it was not easy, except for an hour or two in the late afternoon, to obtain sufficient exercise to preserve health’. Of course, he was well aware that Wilson was becoming increasingly agitated about threats to his administration. However, he himself considered these to be exaggerated.

By now the greater portion of Haldane’s staff had moved to a new Persian HQ at Sar-i-Mil, a few hundred feet higher than Karind and even cooler. So on the night of 24 June, the general again left Baghdad, en route to Sar-i-Mil, arriving there the following day. Before leaving, he assured a none-too-pleased Wilson that ‘if there were any matter outside the ordinary routine work with which my staff who were left there were incompetent to deal, I could be at that city [Baghdad] in a few hours by aeroplane’. However, much to Haldane’s satisfaction, a few days after his arrival in Persia, on 1 July, he received a private letter from Gertrude Bell which suggested that the likelihood of such an eventuality had considerably diminished.

Apparently unaware that only the previous day a serious attack had been launched against a British outpost at Rumaytha, Bell informed

Haldane that, ‘the bottom seems to have dropped out of the agitation and most of the leaders seem only too anxious to let bygones be bygones’, adding, by way of explanation, that ‘I have had many heart-to-heart interviews.’

1

So, understandably, the general spent little time worrying about the size and deployment of his army in Iraq and focused instead upon the social and recreational pleasures of his Persian ‘hill station’.

It wasn’t long before Wilson got to hear of Bell’s letter to the general and understandably he was incandescent. This was not the first time she had gone behind his back, communicating privately with leading British politicians, civil servants and military men, many of whom were personal friends or acquaintances of her rich and well-connected family. Indeed, in retrospect, this pattern of behaviour – which he was now determined to stamp out – had been in evidence since the very beginning of their relationship when Wilson had taken over Sir Percy Cox’s position as civil commissioner following Sir Percy’s departure to the UK (and later Persia) in April 1918.

In August of that year Wilson had received a letter from Hirtzel at the India Office in which the latter referred, in passing, to a missive from Gertrude Bell containing what Hirtzel described as ‘a flaming testimonial’ to Wilson’s qualities and the ‘success of his administration’. Doubtless, at first Wilson was must have been pleased by such a compliment – but then it must also have struck him that here was a woman, considerably junior in rank to himself, who was privately writing to a senior civil servant, offering her opinions as to her superior’s abilities. This was not at all the kind of behaviour appropriate to someone in her position and Wilson quickly realised that – as he put it to a colleague somewhat later – Miss Bell was going to ‘take some handling’.

2

However, ‘handling’ Miss Bell became much more difficult after she returned from Britain via Syria in November 1919, having met Iraqi members of al-‘Ahd like Nuri al-Sa’id and Ja‘far al-‘Askari and become convinced of their moderation. By now, Bell had altogether changed her mind about the ‘success’ of Wilson’s administration and the direction it was taking and was making scant effort to conceal the fact. Indeed, she made it abundantly clear to all that she had been won round to the ideas

promoted by Lawrence and the remnants of the old Cairo-based Arab Bureau that Iraq should move to some form of limited independence as soon as possible, with an Arab emir nominally ruling the country supported by a strong team of British ‘advisors’.

Nor did she refrain from exploiting her social position and family connections to badger government ministers and higher civil servants with her views as to the correct policy towards Iraq, regularly by-passing Wilson and his administration. While admitting she was ‘a minority of one in the Mesopotamian political service’, she wrote frequently to Hirtzel and to Montagu, the secretary of state for India (chummily referring to the latter as ‘Edwin’ in a letter to her father) urging them to recognise the ‘political ambitions’ of those she identified as moderate nationalists and ‘not to try to squeeze the Arabs into our mould’.

3

However, Wilson and his team of young POs remained utterly opposed to any suggestion of ‘independence’, no matter how qualified, and it wasn’t long before their opposition to Bell’s newly acquired views on the viability of an ‘Arab government’ changed into smouldering antagonism. Although Gertrude remained on friendly terms with Frank Balfour, the governor of Baghdad, and the judicial secretary, Edgar Bonham Carter, the remainder of Wilson’s administration grew increasingly hostile towards her. Colonel Leachman, for one, barely recognised her existence; when she lunched in the mess she was met by stony silences, and when Wilson presided over lunch – as he frequently did – he was ‘often as cross as a bear so that the only thing is to leave him alone and not talk to him’. Most hurtful of all, she discovered that her small Baghdad house had been dubbed ‘Chastity Chase’ by some of the younger political and military officers, as though she was some kind of eccentric maiden aunt when, in her own mind, she still longed to find a lifelong soul-mate of the opposite sex.

Convinced that Bell was undermining his own policy, Wilson urged Sir Percy Cox, currently in Persia, to agree to her dismissal, but Cox indicated that he was reluctant to get any further involved in the dispute. So for the time being Wilson resigned himself to her continuing presence. However, for her part, Bell embarked on a project almost

deliberately designed to infuriate Wilson. On 16 May she wrote to her father mentioning that she had launched a series of ‘weekly parties for young nationalists’, the first of which had been attended by ‘thirty young men’. Once Ramadan began, the ‘parties’ commenced at 8.30 p.m. after the sundown evening meal. Bell would hold court in her rose garden, illuminated with old Baghdad lanterns, where her servants offered cold drinks, fruit and cakes to the invited guests.

Most of these ‘young nationalists’ were apparently little more than rich young men flirting with a fashionable notion, flattered to be invited to Miss Bell’s soirées and to chatter with their remarkable female host. None of the members of Haras al-Istiqlal were invited, as far as can be ascertained. It is therefore hardly surprising that Bell’s ‘heart-to-heart interviews’ with such people yielded feeble or misleading information. Indeed, it was one of Miss Bell’s faults that she frequently failed to understand that, out of politeness, many of her Arab acquaintances felt obligated to tell her only what she wanted to hear. Nevertheless, for Wilson, the whole thing was an almost deliberate provocation and it wasn’t long before he found evidence of one of Bell’s more serious indiscretions with which to berate her.

Writing to her father on 14 June, Gertrude recounted how she had had ‘an appalling scene last week with AT’. She had given one of ‘our Arab friends here a bit of information I ought not technically to have given’. Bell had called to see Wilson in his office and when she absentmindedly mentioned disclosing the ‘bit of information’ he had exploded in a ‘black rage’.

‘Your indiscretions are intolerable’, Wilson had shouted, ‘and henceforth you will never again see a paper in this office.’

A crestfallen Bell offered her apologies, but Wilson, choking with anger, continued the attack: ‘You have done more harm than good here. If I hadn’t been going away myself I should have asked for your dismissal months ago – you and your Emir!’

Once again, Bell apologised, and having some useful information of her own to give Wilson she handed it to him, after which he marched out of the office. She did not see him again for two days, but in the meantime

he appears to have cooled down. On the Monday morning following the confrontation Bell found papers on her desk waiting for her as usual.

For a time, Wilson seemed mollified. However, Bell’s letter to General Haldane on 1 July, with its rosy view of the situation, was the final straw. Now, as information flowed into Wilson’s office of the growing crisis on the Euphrates, he believed he had something really serious with which to accuse her. Dispensing with the previous game-playing, he came out into the open and urged Cox – currently in London – to dismiss her. ‘If you can find a job for Miss Bell at home, I think you would be well-advised to do so,’ he wrote, adding, ‘Her irresponsibilities are a source of considerable concern to me and not a little resented by Political Officers.’

4

Yet again, Cox did not accede to Wilson’s requests; but it appears that he did do something – he discussed the matter with the secretary of state, Montagu, who, some weeks later, sent Bell a private telegram containing a strong official rebuke, reminding her that ‘in the present critical state of affairs in Mesopotamia … we should all pull together’, and that if she had views which she wanted the India Office to consider she should ‘either ask the Civil Commissioner to communicate them, or apply for leave and come home and represent them’.

As it happens, Gertrude Bell was not the only individual to receive an official rebuke from the secretary of state for India for a breach of protocol around this time. Wilson himself was accused of committing precisely the same offence. In spite of previous admonitions that he should refrain from criticising the Army of Occupation or its commander (which he had ignored), on 10 July Wilson received a telegram from Montagu informing him that, ‘as general practice you should avoid telegramming me on purely military matters without knowledge and concurrence of GOC.’

However, on the very same day, once again Wilson made it abundantly clear that he had no such intention, telegramming the India Office with what was, in many respects, an accurate and damning indictment of the capabilities of General Haldane’s army.

This lengthy telegram begins with Wilson’s customary analysis of

the causes of the growing unrest, asserting that ‘Military position in Mesopotamia is conditioned by external rather than internal situation. Principal external factors are Bolsheviks, Turks and Syrians in that order.’ The internal situation is described as ‘threatening’ but it would ‘very greatly improve so soon as the external situation has been stabilised’.

5

However, after this risible introduction, Wilson proceeds to identify the army’s deficiencies with a keen eye. The primary requirement is that ‘existing units need to be brought up to strength in personnel and equipment’. Turning first to the RAF, he points out that currently it is ‘not possible to keep more than sixteen aircraft in the air over Mesopotamia and Persia or to make more than six available for any single operation’. On the ground, Wilson complains that ‘armoured cars cannot be sent out of Baghdad owing to weakness or inefficiency of personnel’, reminding the India Office that ‘Tanks have been refused us.’ As for the infantry, ‘British units in country contain such a large proportion of immature and almost untrained young soldiers that they cannot be used for operations during hot weather, whole brunt of which falls on Indian regiments.’

6

The latter were, in any case, under-strength and their transport ‘worn out and inadequate’. Finally, he states that, in his judgement, ‘GHQ Mesopotamia should not again leave Baghdad’, adding disingenuously that, ‘presuming that Her Majesty’s Government required an independent appreciation of the situation, I have not shown this to GOC-in-Chief but I am sending him a copy.’

In fact, by the time Wilson sent this telegram, Haldane had already returned to Baghdad, having arrived on 8 July 1920. Alerted to the critical situation at Rumaytha a few days earlier, he had reluctantly concluded that he had little choice but to move his HQ back to Iraq to deal with the deteriorating situation. Wilson’s deliberate refusal to ‘clear’ his military observations with Haldane before dispatching his telegram therefore indicates the extent to which he was willing to completely ignore the War Office’s complaints about his behaviour as conveyed to him by the India Office. But it also suggests that Wilson knew that the India Office’s reprimand had, perhaps, been little more than ‘going through

the motions’ and that both Montagu and Hirtzel had some sympathy with his complaints.