Equine Massage: A Practical Guide (23 page)

Read Equine Massage: A Practical Guide Online

Authors: Jean-Pierre Hourdebaigt

5.9 Schematic Diagram of a

Stress Point, Stress Point

Technique

(1) stress point, usually found next to

the origin tendon

(2) origin tendon

(3) insertion tendon

We need to remember that inflammation—the body’s natural healing response to any trauma—can lead to a vicious cycle of pain, tension, inflammation, and more pain. Inflammation could therefore produce more stress points. A bad case of “cold back”, an inflammation of the horse’s back muscles, is a good example of this phenomenon. Keep the inflammation under control by using hydrotherapy (chapter 4) to cool the area and maintain the inflammation at a “healthy” level. Use lots of effleurages to ensure proper drainage of the area; otherwise the cycle of pain will never end.

Where Stress Points Form

Stress points can be found anywhere in the muscular structure of the horse. Due to the nature of the horse’s locomotor system, there are some well-known key areas of the skeleton and related specific muscle groups where stress points can usually be found.

Stress points will most often develop at a muscle’s origin tendon, which is the tendon that anchors the muscle to the stable, non-movable body part during a concentric contraction.The origin tendon tends to be quite strong and of good size because it is the anchor attachment for the muscle, and therefore sustains great mechanical strain. The other tendon, the insertion tendon, attaches the muscle to the movable part. This tendon is not as strong or as large as the origin tendon, but will sometimes show stress, especially during

isometric contraction

(to stabilize the body) and

eccentric contraction

(when absorbing great tension during landing, for example).

The horse, like a human, works all of his body at once. Muscle tightening does not remain localized. As one muscle group tightens up, the antagonist group must compensate for the loss of movement and therefore receives extra stress.You will find several stress points during a treatment. Some are related, some are not.

Massage Techniques

111

How Stress Points Feel

A stress point feels like a spot of hardened, rigid tissue about the size of the end of your little finger. It might be slightly swollen and will feel tender to the horse when touched. Also, a tight line of muscle fibers (the muscle bundle associated with the stress point) will be felt across the muscle.

During an acute stage or an inflammation flare-up, stress points will show up very quickly and be easy to detect because of heat and swelling. If the stress point area appears inflamed, use cold hydrotherapy (chapter 4) to numb the nerve endings prior to your treatment. Apply the swelling technique if necessary and follow with the stress point technique (page 112).When inflammation is present, work very lightly, progressing gently into deeper massage over a few sessions.

During chronic stages, the stress points will be more difficult to detect because the symptoms of heat and swelling are less evident.

But with practice, you will develop a feel for stress points and will recognize them easily. If no inflammation is present, you might consider using heat or vascular flush (chapter 4) over the area to loosen the fibers prior to your treatment.

When Stress Points Form

Stress points can form at any time, especially when the animal is under a lot of strain (heavy workload) or fatigued by intense training, or when there is chronic pain from an old injury or chronic condition such as arthritis or rheumatism. Older horses show arthritic deterioration in leg joints; the resulting pain causes muscle tension.This muscle tension triggers more arthritic degeneration in the joints. Massage can help break this cycle of muscle tension and stress point buildup as well as relieving pain and stiffness in the associated muscles. Remember, stress points will sometimes appear in response to a direct trauma.

How Horses Respond to Stress Point

Work

The animal’s response to your work will vary greatly according to the degree of inflammation present. With stress points, the pain reaction you get in relation to your pressure indicates the severity of the stress.To assess the stress point, start with light pressure and then increase gradually.

In human massage therapy, pain caused by a stress point is usually not as sharp as that of a trigger point, but it can be severe on occasion, especially during acute inflammation.The initial contact

112

Equine Massage

on the stress point may elicit some tenderness, but soon after a feeling of relief will replace the original discomfort.

When a stress point is

dormant

(inactive), firm pressure (8 to 12

pounds) applied to it will cause a skin-twitching reaction; after a couple of minutes, a general release of the muscle will follow.

Horses often seem to enjoy this form of work.

When a stress point is

active

(inflamed), the reaction will be more pronounced.As you apply medium pressure (5 to 8 pounds) to an active stress point, you will notice excessive skin twitching and flinching; the animal will pull away from the pressure. If the reaction is sharp or if the adjacent muscles are showing excessive tightness, you may suspect that the muscle might be close to full spasm. Be very gentle and methodical in your approach.

The Stress Point Technique

The stress point technique consists of two stages. The first deals with the Golgi apparatus nerve cell, the other deals with the muscle spindle nerve cell. (See pages 107–108 for an explanation of these nerve cells.) As you locate a stress point, identify the muscle it belongs to.

First Stage

A thorough massage of the origin tendon (with pressure applied toward the bone) will stretch the sensory nerve endings (Golgi nerve cells) located in the tendons. While being stretched, the Golgi nerve cell will send nerve impulses to the brain and cause a reflex action. This will relax the corresponding motor nerve responsible for the stress point. The nervous reflex might take a few seconds to a few minutes to occur. Small stress points might release very quickly or might take several minutes. Do not overwork them.

If the stress point area appears inflamed, use cold hydrotherapy to numb the nerve endings. Otherwise, if the area does not appear inflamed, consider using heat or vascular flush over the area to loosen the fibers (see chapter 4).

Start your technique with light strokings for a few seconds to relax and comfort your animal. Then weave your moves into effleurage or wringings to increase circulation and warm up the area. Proceed with some thorough kneading moves over the tendon where you found the stress point.Then with your thumb or fingertips apply gentle pressure (2 or 3 pounds) to establish the initial contact and evaluate the degree of inflammation.

Progressively increase your pressure to 5 pounds, then up to 10 to 15 pounds as the release occurs. Depending on the location of the

Massage Techniques

113

stress points, you may use the elbow technique (page 100) to work over large muscle groups, increasing your pressure to 20 or 25

pounds.

These moves will work the fibers against the bone, increasing the blood flow to the area. Watch your animal’s reaction as you proceed and adjust your pressure accordingly. Hold the pressure until you feel the stress point let go. Follow with lots of effleurages to thoroughly drain the area. If after a minute no release has happened, progressively release your pressure, intersperse with a few effleurages, and repeat the procedure of applying pressure to the stress point until it releases.

Second Stage

The second stage of this technique consists of working the muscle spindle nerve cells. By gently frictioning the muscle spindle you will reset nerve awareness and fully relax the muscle.This will loosen the tight fibers, increase circulation through the muscle, restore freedom of motion to the fibers, and decrease painful symptoms.

Move your thumb or fingertips very gently across the grain of the muscle, perpendicular to the fibers, all along its course. Use a medium pressure of 8 to 12 pounds. Eventually, you may do this to the whole muscle bundle. This action will loosen the muscle spindle nerve cells. Intersperse your gentle frictions with effleurages every 20 to 30 seconds to drain the area.

Be aware that if you friction over the muscle spindle too vigorously or with too much pressure, it will stretch the muscle spindle and cause the muscle to react by contracting (this feature is used to strengthen weak muscles; see neuromuscular technique, page 106). Be gentle during this phase of the technique.

Follow up with thorough drainage (wringings, effleurages) to bring in new blood, nutrients, and oxygen and to remove toxins from the site. The muscle will feel better immediately. The horse should be lightly exercised for 5 to 10 minutes (longeing, walk/trot) immediately after the treatment.

When the horse is warm, use stretching exercises to further the release of the affected muscle groups (see chapter 8).

If you do not see any improvement after working on a stress point for 3 to 5 minutes, stop. Overworking the tissues will aggravate the inflammation. Especially in chronic tension cases, it sometimes takes several treatments to relieve a stress point. After all, these kinds of stress points have been there for a while; it may take up to five treatments to bid them adieu! If inflammation is present, use hydrotherapy after your treatment to cool the nerve

114

Equine Massage

endings and elicit vasodilation. Keep records of your work and of the results produced (see chapter 16).

The stress point technique is very efficient when properly applied. If underworked, a stress point will still present the same symptoms with little or no improvement. Overworking a stress point is more dramatic, resulting in stronger inflammation (heat, swelling, pain). In that case, immediately apply some cold hydrotherapy to relieve the symptoms. Give the animal a couple of days of rest before further massage in that area.

Regular practice will allow you to experiment and gain expertise.

The Origin-Insertion

Technique

The origin-insertion technique, which is derived from the neuromuscular technique, is applied on both tendons and will assist in releasing muscle contractures (hypertonicity) and muscle spasms, or when dealing with muscle weakness (hypotonicity).

The term “origin-insertion” refers to the origin and the insertion tendons of a muscle.The origin tendon anchors to the most stable, least movable bone, whereas the insertion tendon attaches the muscle to the movable part, so that during contraction the insertion is brought closer to the origin.The origin tendon is usually stronger and bigger than the insertion tendon because its anchor attachment sustains greater stress. Stress is responsible for most of the problems found close to origin tendons.

Contracture

can be found anywhere in the belly of the muscle.

It is a hypertonic state in which muscle fibers cannot let go of their contractile power. Due to high stress, pain, and inflammation, many motor nerve impulses cause the muscle fibers to contract indefinitely. Contractures are responsible for the decrease of muscle action, which results in

congestion

(lack of fluid circulation in the muscle fibers) and in a restricted movement (shorter stride).

By thoroughly massaging the origin and insertion tendons, we stretch the sensory nerve endings, which send relaxation impulses to the brain. In response, the corresponding motor nerve signal causing the muscle to remain contracted will cease, releasing the spasm. This release might occur quickly, depending on the stress level, the severity of the spasm, and whether the spasm is associated with a trauma or a wound. Sometimes a spasm will let go several hours after the treatment.

Your knowledge of the muscle group you are working on, where muscles attach and their direction, is most important to the effectiveness of the treatment.

Massage Techniques

115

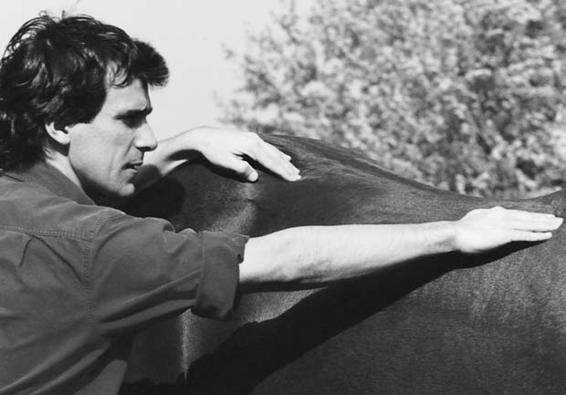

5.10 Origin-Insertion Technique:

Here done on the longissimus dorsi

muscle.

After you locate the problem and ascertain which muscle you need to work, start by lightly stroking the area to soothe and comfort the horse. Then use light effleurages, wringings, and kneadings to stimulate circulation and warm up the area.

To release a spasm or a contracture, begin by using a gentle but firm double-thumb kneading over the origin tendon, pressing it against the bone (away from the belly of the muscle). Apply pressure at approximately 5 to 10 pounds (15 to 20 on large muscle groups) for approximately 2 or 3 minutes. Intersperse with some effleurage every 30 seconds. Then repeat the same procedure on the insertion tendon.

Next, use thorough effleurage to drain the entire muscle area.

Using your fingertips, friction the whole muscle lightly across the fibers. Repeat these moves 2 or 3 times and follow with a thorough drainage.

Depending on the severity and degree of inflammation present in the tissue, the origin-insertion technique should not continue more than 10 minutes. Avoid overworking; it will only aggravate the situation. It is better to repeat the treatment several times over a few days than risk irritating the nerve endings or worsening the inflammation in the muscle fibers on the first treatment.