Essence and Alchemy (24 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

The deceased who were not naturally sweet-smelling might be made so. In ancient India, corpses were washed and anointed with sandalwood oil and turmeric. The Romans poured aromatic oils over the ashes of their dead, a custom to which the Catholic rite of extreme unction at the point of death is distantly related. The ancient Egyptians used copious amounts of fragrance in funerals and other religious rituals, and packed more along with or sometimes inside of the dead, in the form of long-lasting unguents whose recipes were closely guarded by the priests. (When the jars of unguents found in King Tut's tomb were opened after three thousand years, they were still fragrant.) When men and women of rank died, their faces were perfumed and painted as for a festival. The organs were removed and replaced with precious spices, gums, and oils, and the body, too, was painted. Then the corpse was wrapped in nearly a mile of linen bandages saturated with ointments and interred with amulets and charms made of glass or gold to protect it on its last journey.

Behind all of these practices is the idea that the pure in spirit aspire to become pure spiritâliterally, to become scent. But as synthetic ingredients constricted the palette of essential oils in common use and aromatics faded from religious practice, leaving Catholic priests swinging the same tired incense in their censers, the idea lost its potency. Scent has become no more than a metaphor for spirit, and not a particularly vivid one at that.

The popularity of aromatherapy, which has made a number of natural essences readily accessible again, has made it possible to resurrect the connection between spirituality and scent. Whatever your beliefs, you can use scent to bring depth and immediacy to meditation and other spiritual practices.

Â

Â

M

editatio

is the alchemical term for an inner dialogue with an unseen beingâperhaps God, one's good angel, or oneself. According to Jung, “When the alchemists

132

speak of

meditari

they do not mean mere cogitation, but explicitly an inner dialogue and hence a living relationship to the answering voice of the âOther' in ourselves, i.e., of the unconscious. The use of the term

meditation

in the Hermetic dictum âAnd as all things proceed from the One through the meditation of the One' must therefore be understood in this alchemical sense as a creative dialogue, by means of which things pass from the unconscious potential state to a manifest one.” Such an inner dialogue is an essential part of creative and explicitly spiritual processes alike, allowing one to come to terms with unseen and unconscious forces before taking action.

editatio

is the alchemical term for an inner dialogue with an unseen beingâperhaps God, one's good angel, or oneself. According to Jung, “When the alchemists

132

speak of

meditari

they do not mean mere cogitation, but explicitly an inner dialogue and hence a living relationship to the answering voice of the âOther' in ourselves, i.e., of the unconscious. The use of the term

meditation

in the Hermetic dictum âAnd as all things proceed from the One through the meditation of the One' must therefore be understood in this alchemical sense as a creative dialogue, by means of which things pass from the unconscious potential state to a manifest one.” Such an inner dialogue is an essential part of creative and explicitly spiritual processes alike, allowing one to come to terms with unseen and unconscious forces before taking action.

Certain oils have a long history of association with meditation and spiritual practices. Frankincense, sandalwood, and myrrh have long been recognized by many religious traditions for their ability to tranquilize and clarify, and in general to bring us back to ourselves. Benzoin's sweet, resinous odor steadies and focuses the mind for meditation and contemplation. Cedarwood is a grounding oil that mobilizes the transformative powers of the will. Clary sage is an aid to inspiration and insight. Lavender absolute calms the spirit, while bergamot helps one to let go.

Aromatics can be used to purify the place where you meditate, and to create an atmosphere conducive to peaceful reflection. The consistent use of a blend that you have set aside expressly for the

purpose of meditation will give it the power to transport you into the desired state of consciousness. You can use it to anoint parts of your body or an object to hold, or you can make it into a solid perfume that you carry with you to help you recapture the serenity of your meditation time.

purpose of meditation will give it the power to transport you into the desired state of consciousness. You can use it to anoint parts of your body or an object to hold, or you can make it into a solid perfume that you carry with you to help you recapture the serenity of your meditation time.

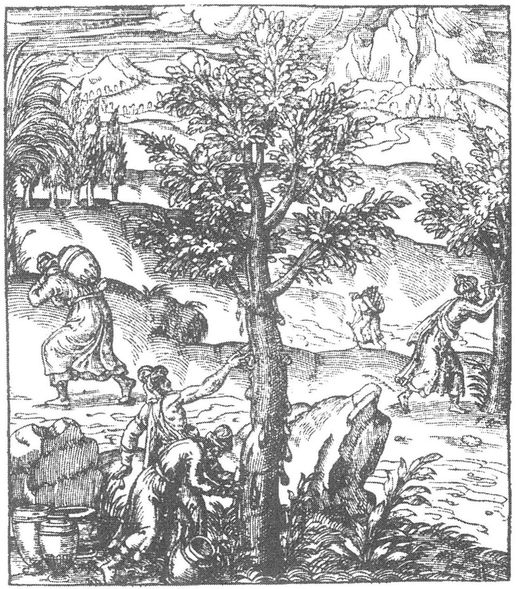

Harvesting frankincense and myrrb

You can meditate on scent itself, an excellent way of setting aside the concerns of the day, calming the mind, and deepening and slowing the breath. For this practice you can simply use blotter strips, but

you may want to make a single-note solid perfume to rub on your hands or wrists so that you can inhale it during your meditation. Use a rich, multilayered, full-bodied essence such as orange flower absolute, labdanum, lavender concrete, or (my particular favorite) pure rose absolute. As always, you need not be limited by my suggestions, and you should be guided by your own affinities. (See chapter 7 for instructions on making solid perfumes.)

you may want to make a single-note solid perfume to rub on your hands or wrists so that you can inhale it during your meditation. Use a rich, multilayered, full-bodied essence such as orange flower absolute, labdanum, lavender concrete, or (my particular favorite) pure rose absolute. As always, you need not be limited by my suggestions, and you should be guided by your own affinities. (See chapter 7 for instructions on making solid perfumes.)

Here is a guided meditation that focuses on scent:

Sit in a comfortable position. Hold the blotter strip or the fragrant part of your hands or wrists up to your nose and inhale deeply three times. Keeping your eyes open, imagine your consciousness dissolving outward into the scent, as if you are touching it, merging with it, flowing into it. When you reach the point of saturation, close your eyes in order to detach yourself from all senses but smell.

Descend deeply inside, bearing the essence of the scent you have chosen, and touch it with your vision of the scent. Build an inner picture of the essenceâthe essence of the essence. Imagine it as a phantasm, an animal, a memory, anything that seems to you to be entirely conjured by the deep impression of the scent. You will find that each scent you meditate upon creates a different internal image and meditative experience.

Turn outward again. Repeat the outer phase and inner phase in alternation until your soul feels full. This exercise will help you to carry in your consciousness a living connection with a particular essence, and through it, with the spiritual dimension of scent in general.

Here is a formula for a blend to use specifically in meditation. Try placing it on the skin between the thumb and forefinger of each

hand, then place your hands together, bring them to your face, and inhale deeply. (This blend also makes an excellent solid;

see here

)

hand, then place your hands together, bring them to your face, and inhale deeply. (This blend also makes an excellent solid;

see here

)

MEDITATION BLEND

Â

15 ml jojoba oil

30 drops frankincense

18 drops sandalwood

12 drops myrrh

18 drops rose absolute

18 drops clary sage

18 drops Virginia cedarwood

30 drops pink grapefruit

24 drops bois de rose

40 drops bergamot

30 drops frankincense

18 drops sandalwood

12 drops myrrh

18 drops rose absolute

18 drops clary sage

18 drops Virginia cedarwood

30 drops pink grapefruit

24 drops bois de rose

40 drops bergamot

Scented objects such as rosaries have been used in many religions. On feast days, early Christian priests wore garlands of rosebuds or beads made from rose petals, ground and blended with fixatives into an aromatic paste, then rolled into balls and pierced with a needle. The circular form of the rosary suggested eternity and eternal devotion. And perhaps because the rose is associated with the blood of Christ and the purity of the Virgin Mary, the custom caught on. Or maybe it was simply that, warmed in the hands during prayer, the beads released a mesmerizing scent. As Baudelaire recognized, “The rosary is a medium, a vehicle; it is prayer put at everybody's disposal.”

Here is a nineteenth-century recipe

133

:

133

:

Gather the roses on a dry day and chop the petals very finely. Put them in a sauce pan and barely cover with water. Heat for an hour but do not let it boil. Repeat this for three days and if necessary add more water. The deep black beads made

from rose petals are made this rich color by warming in a rusty pan. It is important never to let the mixture boil but each day to warm it over a moderate heat. Make the beads by working the pulp with the fingers into balls. When thoroughly well worked and fairly dry press on to a bodkin to make holes in the centers of the beads. Until they are perfectly dry the beads have to be moved frequently on the bodkin or they will be difficult to remove without breaking them.

from rose petals are made this rich color by warming in a rusty pan. It is important never to let the mixture boil but each day to warm it over a moderate heat. Make the beads by working the pulp with the fingers into balls. When thoroughly well worked and fairly dry press on to a bodkin to make holes in the centers of the beads. Until they are perfectly dry the beads have to be moved frequently on the bodkin or they will be difficult to remove without breaking them.

French roses awaiting extraction

Without going to so much trouble, it is a lovely idea to make an object to hold in your hands during meditation practice, and most people find that it helps them to focus. I have experimented with silk ribbon, leather cord, silk fabric, and chamois (soft leather made from any of various animal skins). Chamois feels wonderful in the hand and contributes its own animal undertones, creating a more profound depth of aroma. (Not surprisingly, chamois was used in the original Peau d'Espagne.) You can buy chamois at an automotive supply shop (many people use it for polishing their cars).

To make scented chamois:

Wash the material by hand, using a mild detergent to remove the light oil with which it is cured. Rinse it thoroughly, stretch it out, and let it dry thoroughly. Cut it into shapes that feel right to hold during your meditation, or cut into strips and make a braid of them.

Choose an essence with which you have a strong affinityâor a few, but keep it simple. (I particularly love how base notes like clary sage concrete, labdanum, and white spruce absolute marry with chamois, but my very favorite is amber.) Put a few drops directly on the cloth and allow it to penetrate. Over time, the notes will fade but will not disappear entirely. Add more scent each time you meditate, layering scent upon scent until the chamois is completely impregnated with essences.

A solid perfume is a wonderful get-well gift that carries on the healing tradition of which perfumery has long been a part. I created a solid perfume for a friend to take to someone who was recovering from a car accident. My friend said, “I brought you a bouquet of flowers” and handed her a silver pillbox filled with a floral blend. (

See here

.)

See here

.)

Death of a Rolling Stone: The Brian Jones Story

Â

When Talk Is Not Cheap

(with Robin Lakoff)

(with Robin Lakoff)

Â

The Story of Your Life: Becoming the Author of Your Experience

Getting started in perfumery requires very little in the way of equipment, as you saw in Chapter 2. And a basic set of essences is not very expensive either. To provide enough variety in your assortment of essences to spark your creativity and sustain your enthusiasm, I would recommend purchasing the second set of essences as well.

I have marked with an asterisk those that are more costly

.

Those that you can easily find in a health food store or natural grocery are marked with a cross

. (Buy 1/6 ounce or 5 ml)

I have marked with an asterisk those that are more costly

.

Those that you can easily find in a health food store or natural grocery are marked with a cross

. (Buy 1/6 ounce or 5 ml)

BASIC SET OF ESSENCES

Base notes

:

:

Benzoin resin

Labdanum absolute

Oakmoss absolute

Peru Balsam resin

â

Vetiver essential oil

â

Frankincense essential oil

Labdanum absolute

Oakmoss absolute

Peru Balsam resin

â

Vetiver essential oil

â

Frankincense essential oil

Â

Middle notes:

â

Clary Sage essential oil

Clove absolute

Ylang ylang concrete

Lavender absolute

*

Jasmine concrete

Nutmeg absolute

Clary Sage essential oil

Clove absolute

Ylang ylang concrete

Lavender absolute

*

Jasmine concrete

Nutmeg absolute

Â

Top notes:

SECOND SET OF ESSENCES

Base notes:

Â

Middle notes:

*

Neroli essential oil

*

Rose absolute

*

Tuberose absolute

Litsea cubeba essential oil

Geranium essential oil

Neroli essential oil

*

Rose absolute

*

Tuberose absolute

Litsea cubeba essential oil

Geranium essential oil

Â

Top notes

:

:

EQUIPMENT

2 10-ml beakers with markings for 15 ml and 30 ml

6 glass droppers

a dozen small glass bottles

6 glass droppers

a dozen small glass bottles

skewers for stirringâuse bamboo shish-kebab sticks cut into shorter lengths, cheap wooden chopsticks, or glass cocktail stirrers

perfume blotter strips

perfume alcohol for blending

rubbing alcohol for cleaning droppers

small glasses, shot or otherwise, for holding rubbing alcohol

metal or plastic measuring spoons

small adhesive labels for labeling essences and blends

coffee filters and unbleached filter papers (for filtering out solids)

perfume alcohol for blending

rubbing alcohol for cleaning droppers

small glasses, shot or otherwise, for holding rubbing alcohol

metal or plastic measuring spoons

small adhesive labels for labeling essences and blends

coffee filters and unbleached filter papers (for filtering out solids)

Â

For making solids:

beeswax

small cheese grater

hot plate (optional)

compacts

small cheese grater

hot plate (optional)

compacts

SOURCES

Aftelier Perfumes

510-841-2111

www.aftelier.com

510-841-2111

www.aftelier.com

Â

Natural perfumes:

Â

Beginning essence and equipment kits

The Natural Perfume Distance Learning Tutorial

The Aftelier Natural Perfume Wheel

Essential oils, absolutes, and concretes sourced by Mandy Aftel

Â

For perfume alcohol

Â

Bryant Laboratory

510-526-3141

[email protected]

510-526-3141

[email protected]

Â

Remet

877-939-0171

www.remet.com

877-939-0171

www.remet.com

Â

For grape alcohol:

Â

Marian Farms (Demeter certified)

559-276-2185

www.marianfarmsbiodynamic.com

559-276-2185

www.marianfarmsbiodynamic.com

Â

Vie-Del

559-834-2525

[email protected]

559-834-2525

[email protected]

Â

For essential oils, absolutes, and concretes:

Â

Essential Oil Company

800-729-5912

www.essentialoil.com

800-729-5912

www.essentialoil.com

Â

The Essential Oil University

812-945-5000

www.essentialoils.org

812-945-5000

www.essentialoils.org

Â

Liberty Natural Products

800-289-8427

www.libertynatural.com

800-289-8427

www.libertynatural.com

Â

Original Swiss Aromatics

415-479-9120

www.originalswissaromatics.com

415-479-9120

www.originalswissaromatics.com

Â

Scents of Knowing

808-573-6733

www.scentsofknowing.com

808-573-6733

www.scentsofknowing.com

Â

Sunrose Aromatics

718-794-0391

www.sunrosearomatics.com

718-794-0391

www.sunrosearomatics.com

Â

White Lotus Aromatics

Fax: 510-528-9441

www.whitelotusaromatics.com

Fax: 510-528-9441

www.whitelotusaromatics.com

Â

For lab equipment:

Â

Bryant Laboratory

510-526-3141

[email protected]

510-526-3141

[email protected]

Â

VWR catalogue

800-932-5000

www.vwr.com

800-932-5000

www.vwr.com

Â

For perfume blotter strips:

Â

Orlandi

631-756-0110

www.orlandi-usa.com

631-756-0110

www.orlandi-usa.com

Â

For bottles and packaging:

Â

ABA Packaging

800-443-9799

www.abapackaging.com

800-443-9799

www.abapackaging.com

Â

O. Berk Company

908-851-9500

www.Oberk.com

908-851-9500

www.Oberk.com

Â

SKS Bottle and Packaging

518-899-7488

www.sks-bottle.com

518-899-7488

www.sks-bottle.com

Â

Sunburst Bottle

916-929-4500

www.sunburstbottle.com

916-929-4500

www.sunburstbottle.com

Â

For toiletries supplies:

Â

Â

For small compacts and lockets for solid perfume:

Â

Eli Metal Products Company

800-552-4554

800-552-4554

Other books

The Beloved by Annah Faulkner

Secret Archives of Sherlock Holmes, The, The by Thomson, June

Buried by Robin Merrow MacCready

A Little Bit of Charm by Mary Ellis

Private 04 - Confessions by Kate Brian

Playing Around by Gilda O'Neill

The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2011 by Mary Roach

Just Desserts by Jan Jones

Dharma Feast Cookbook by Theresa Rodgers

Fair Peril by Nancy Springer