Essence and Alchemy (3 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

If scent is uniquely powerful, it can also be uniquely comforting, instantly erasing the passage of time. “A scent may drown years

12

in the odor it recalls,” observes Walter Benjamin. At the same time, both the scent and the memories associated with it remain partly out of focus and out of view. “When it is said

13

that an object occupies a

large space in the soul or even that it fills it entirely, we ought to understand by this simply that its image has altered the shade of a thousand perceptions or memories, and that in this sense it pervades them, although it does not itself come into view,” notes the philosopher Henri Bergson. A remembered smell spills into consciousness baskets full of inchoate memories and the feelings entwined with them, permeating the emotional aura of the memories with a richness that is both exquisite and vague.

12

in the odor it recalls,” observes Walter Benjamin. At the same time, both the scent and the memories associated with it remain partly out of focus and out of view. “When it is said

13

that an object occupies a

large space in the soul or even that it fills it entirely, we ought to understand by this simply that its image has altered the shade of a thousand perceptions or memories, and that in this sense it pervades them, although it does not itself come into view,” notes the philosopher Henri Bergson. A remembered smell spills into consciousness baskets full of inchoate memories and the feelings entwined with them, permeating the emotional aura of the memories with a richness that is both exquisite and vague.

These memories

14

, messengers from the unconscious, remind us of what we are dragging behind us unawares. But, even though we may have no distinct idea of it, we feel vaguely that our past remains present to us ⦠Doubtless we think with only a small part of our past, but it is with our entire past, including the original bent of our soul, that we desire, will, and act. Our past, then, as a whole, is made manifest to us in its impulse; it is felt in the form of tendency, although a small part of it only is known in the form of idea.

14

, messengers from the unconscious, remind us of what we are dragging behind us unawares. But, even though we may have no distinct idea of it, we feel vaguely that our past remains present to us ⦠Doubtless we think with only a small part of our past, but it is with our entire past, including the original bent of our soul, that we desire, will, and act. Our past, then, as a whole, is made manifest to us in its impulse; it is felt in the form of tendency, although a small part of it only is known in the form of idea.

Scent pervades memory but remains invisible, as if emanating from its interior, the way it seems to emanate from the interior of objects. Its nature makes it an apt metaphor for spiritual concepts, for it “can readily be understood

15

as conveying inner truth and intrinsic worth,” observes Classen. “The common association of odor with the breath and with the life-force makes smell a source of elemental power, and therefore an appropriate symbol and medium for divine life and power. Odors can strongly attract or repel, rendering them forceful metaphors for good and evil. Odors are also ethereal, they cannot be grasped or retained; in their elusiveness they convey a sense of both the mysterious presence and the mysterious absence of God. Finally, odors are ineffable, they transcend our ability to define them through language, as religious experience is said to do.”

15

as conveying inner truth and intrinsic worth,” observes Classen. “The common association of odor with the breath and with the life-force makes smell a source of elemental power, and therefore an appropriate symbol and medium for divine life and power. Odors can strongly attract or repel, rendering them forceful metaphors for good and evil. Odors are also ethereal, they cannot be grasped or retained; in their elusiveness they convey a sense of both the mysterious presence and the mysterious absence of God. Finally, odors are ineffable, they transcend our ability to define them through language, as religious experience is said to do.”

Â

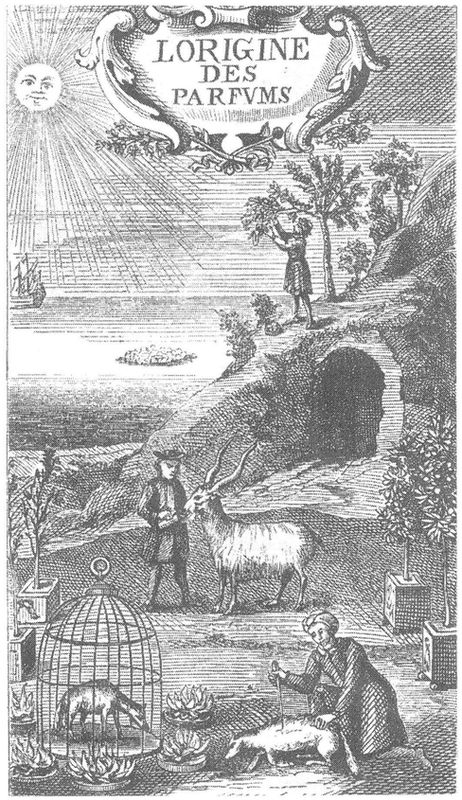

The Origin of Perfumes,

seventeenth-century engraving

seventeenth-century engraving

P

erfume, as a kind of scent, is all of these things. It is also, paradoxically, a product that is essentially worthless, its only function to provide pleasure. In this sense, too, it straddles the line between the tangible and the intangible, the earthly and the ethereal, the real and the magical. The transcendental properties of fragrance were recognized as far back in our history as we can trace. Indeed, the earliest perfumers we know of were Egyptian priests, who blended the juices expressed from succulent flowers and plants, the pulp of fruits, spices, resins and gums from trees, meal made from oleaginous seeds, wine, honey, and oils to make incense and unguents.

erfume, as a kind of scent, is all of these things. It is also, paradoxically, a product that is essentially worthless, its only function to provide pleasure. In this sense, too, it straddles the line between the tangible and the intangible, the earthly and the ethereal, the real and the magical. The transcendental properties of fragrance were recognized as far back in our history as we can trace. Indeed, the earliest perfumers we know of were Egyptian priests, who blended the juices expressed from succulent flowers and plants, the pulp of fruits, spices, resins and gums from trees, meal made from oleaginous seeds, wine, honey, and oils to make incense and unguents.

When Moses returned from exile in Egypt, the Lord commanded him to compound a holy oil from olive oil and fragrant spices. The Jews brought back with them as well the Egyptian practice of applying fragrant oils and unguents to the body. In the basement of a house in Jerusalem that dates from the first century B.C., archaeologists have uncovered evidenceâovens, cooking pots, and mortarsâof a perfume workshop for the nearby temple. Wall carvings and paintings from the period document the process of perfume-making in detail.

From Egyptian times, however, fragrant blends were used for bodily adornment and curative purposes as well as in religious ceremonies. “This will be the way of the king ⦠and he will take your daughters to be perfumers,” says the Bible (I Sam. 8:11â13). The Jerusalem wall paintings reveal that the perfumers were indeed women, and that they were as likely to serve the court as the temple. Moreover, aromatic substances, being rare, precious, and easily transported by caravan, were used for barterâcostus, sandalwood, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, and, most especially, frankincense and myrrh. These ingredients were so important and so difficult to obtain that the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut sent a fleet of ships to Punt (Somalia) to bring back myrrh seedlings to plant in her temple.

The aesthetic use of scent reached its moment of greatest excess during the heyday of the Roman Empire

16

. Wealthy Romans used scented doves to perfume the air at feasts, rubbed dogs and horses with unguents, brushed walls with aromatics, and sprinkled floors with flower petals. The emperor Nero is reported to have had Lake Lucina covered in rose petals when he threw a feast there, and he was said to sleep on a bed of petals. (Supposedly, he suffered insomnia if even one of them happened to be curled.)

16

. Wealthy Romans used scented doves to perfume the air at feasts, rubbed dogs and horses with unguents, brushed walls with aromatics, and sprinkled floors with flower petals. The emperor Nero is reported to have had Lake Lucina covered in rose petals when he threw a feast there, and he was said to sleep on a bed of petals. (Supposedly, he suffered insomnia if even one of them happened to be curled.)

But perfume as we know it could not have taken shape without alchemy, the ancient art that undertook to convert raw matter, through a series of transformations, into a perfect and purified form. Often referred to as the “divine” or “sacred” art, alchemy has complex and deep roots that reach back to ancient China, India, and Egypt, but it came into its own in medieval Europe and flourished well into the seventeenth century.

The ways of the alchemists were shrouded in secrecy. They tended to be solo practitioners who maintained their own laboratories and rarely took pupils or associated in societies, even secret ones. They did leave records, however, and they quote one another extensively, for the most part in evident agreement. Agreement as to what is another question. On the one hand, their work, or

opus

, was practical, resembling a series of chemistry experiments. And indeed the alchemists deserve credit for refining the process of distillation, which was of enormous importance to the evolution of perfumery, not to mention wine-making, chemistry, and other branches of industry and science. Yet it is difficult to discern from their writings almost anything definite about their processes. “In my opinion it is quite hopeless to try to establish any kind of order in the infinite chaos of substances,” fumed Carl Jung

17

, who was fascinated by alchemy and wrote about it extensively. “Seldom do we get even an approximate idea of how the work was done, what materials were used, and what results were achieved. The reader usually finds himself in the most impenetrable darkness when it comes to the names of substancesâthey could mean almost anything.” The alchemists themselves had difficulty understanding one another's symbols and diagrams, and sometimes they seem confounded even as to the meaning of their own.

opus

, was practical, resembling a series of chemistry experiments. And indeed the alchemists deserve credit for refining the process of distillation, which was of enormous importance to the evolution of perfumery, not to mention wine-making, chemistry, and other branches of industry and science. Yet it is difficult to discern from their writings almost anything definite about their processes. “In my opinion it is quite hopeless to try to establish any kind of order in the infinite chaos of substances,” fumed Carl Jung

17

, who was fascinated by alchemy and wrote about it extensively. “Seldom do we get even an approximate idea of how the work was done, what materials were used, and what results were achieved. The reader usually finds himself in the most impenetrable darkness when it comes to the names of substancesâthey could mean almost anything.” The alchemists themselves had difficulty understanding one another's symbols and diagrams, and sometimes they seem confounded even as to the meaning of their own.

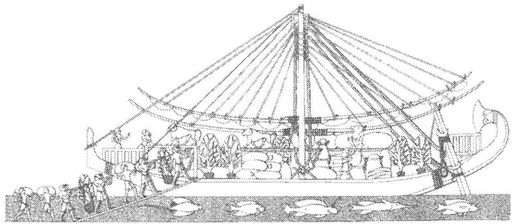

Loading myrrh trees on a ship, after fifteenth-century B.C. relief

There was a reason for this obscurity, Jung explains:

Although the alchemist was interested in the chemical part of the work he also used it to devise a nomenclature for the psychic transformations that really fascinated him. Every original alchemist built himself, as it were, a more or less individual edifice of ideas, consisting of the dicta of the philosophers and of miscellaneous analogies to the fundamental concepts of alchemy. Generally these analogies are taken from all over the place. Treatises were even written for the purpose of supplying the artist with analogy-making material. The method of alchemy, psychologically speaking, is one of boundless amplification. The

amplificatio

is always appropriate when dealing with some obscure experience which is so vaguely adumbrated that it must be enlarged and expanded by being set in a psychological context in order to be understood at all.

amplificatio

is always appropriate when dealing with some obscure experience which is so vaguely adumbrated that it must be enlarged and expanded by being set in a psychological context in order to be understood at all.

At bottom, the alchemists believed that their work was divinely inspired and could be brought to fruition only with divine assistance. Theirs was not a “profession” in the usual sense; it was a calling. Those who were called to it would comprehend its metaphors and express them, in turn, in their own.

The philosophy of alchemy expressed the conviction that the spark of divinityâthe

quinta essentia

18

âcould be discovered in matter. In the words of Paracelsus, the enormously influential sixteenth-century doctor and alchemist, “The quinta essentia is that which is extracted from a substanceâfrom all plants and from everything which has lifeâthen freed of all impurities and perishable parts, refined into highest purity and separated from all elements ⦠The inherency of a thing, its nature, power, virtue, and curative efficacy,

without any ⦠foreign admixture ⦠that is the quinta essentia. It is a spirit like the life spirit, but with this difference, that the spiritus vitea, the life spirit, is imperishable ⦠The quinta essentia being the life spirit of things, it can be extracted only from the perceptible, that is to say material, parts.” The ultimate goal was to reunite matter and spirit in a transformed state, a miraculous entity known as the Elixir of Life (sometimes called the Philosopher's Stone). Some believed that those who imbibed it would prolong their lives to a thousand years, others that it yielded not only perpetual youth but an increase of knowledge and wisdom.

quinta essentia

18

âcould be discovered in matter. In the words of Paracelsus, the enormously influential sixteenth-century doctor and alchemist, “The quinta essentia is that which is extracted from a substanceâfrom all plants and from everything which has lifeâthen freed of all impurities and perishable parts, refined into highest purity and separated from all elements ⦠The inherency of a thing, its nature, power, virtue, and curative efficacy,

without any ⦠foreign admixture ⦠that is the quinta essentia. It is a spirit like the life spirit, but with this difference, that the spiritus vitea, the life spirit, is imperishable ⦠The quinta essentia being the life spirit of things, it can be extracted only from the perceptible, that is to say material, parts.” The ultimate goal was to reunite matter and spirit in a transformed state, a miraculous entity known as the Elixir of Life (sometimes called the Philosopher's Stone). Some believed that those who imbibed it would prolong their lives to a thousand years, others that it yielded not only perpetual youth but an increase of knowledge and wisdom.

As Jung perceived, alchemical processes were “so loaded with unconscious

19

contents that a state of

participation mystique

or unconscious identity” arose between the alchemist and the substances with which he worked. The analogy, if unconscious, was nevertheless pervasive. “The combination of two bodies

20

he saw as a marriage,” F. Sherwood Taylor observes in

The Alchemists.

“The loss of their characteristic activity as death, the production of something new as a birth, the rising up of vapors, as a spirit leaving the corpse, the formation of a volatile solid, as the making of a spiritual body. These conceptions influenced his idea of what should occur, and he therefore decided that the final end of the substances operated on should be analogous to the final end of manâa new soul in a new, glorious body, with the qualities of clarity, subtlety and agility.”

19

contents that a state of

participation mystique

or unconscious identity” arose between the alchemist and the substances with which he worked. The analogy, if unconscious, was nevertheless pervasive. “The combination of two bodies

20

he saw as a marriage,” F. Sherwood Taylor observes in

The Alchemists.

“The loss of their characteristic activity as death, the production of something new as a birth, the rising up of vapors, as a spirit leaving the corpse, the formation of a volatile solid, as the making of a spiritual body. These conceptions influenced his idea of what should occur, and he therefore decided that the final end of the substances operated on should be analogous to the final end of manâa new soul in a new, glorious body, with the qualities of clarity, subtlety and agility.”

Following the dictum

solve et coagula

(dissolve and combine), the alchemist worked to transform body into spirit and spirit into body; to volatilize that which is fixed, and to fix that which is volatile. But the “base material” he worked upon and the “gold” he produced may also be understood as man himself, in his quest to perfect his own nature.

solve et coagula

(dissolve and combine), the alchemist worked to transform body into spirit and spirit into body; to volatilize that which is fixed, and to fix that which is volatile. But the “base material” he worked upon and the “gold” he produced may also be understood as man himself, in his quest to perfect his own nature.

A repeating axiom in the literature of alchemy is: “What is above is as that which is below, and what is below is as that which is above.” Alchemists believed in an essential unity of the cosmos; that there is a correspondence between things physical and spiritual, and that the same laws operate in both realms. “The Sages have been taught of God that this natural world is only an image and material copy of a heavenly and spiritual pattern,” wrote the seventeenth-century Moravian alchemist Michael Sendivogius; “that the real existence in this world is based upon the reality of the celestial archetype; and that God had created it in imitation of the spiritual and invisible universe.”

Other books

Cursed Heart (Cursed #2.5) by T H Snyder

Mystery by Jonathan Kellerman

Rotting Hill by Lewis, Wyndham

Microsoft Word - Document1 by nikka

Small-Town Mom by Jean C. Gordon

Athyra by Steven Brust

Worth The Shot (The Bannister Brothers #2) by Jennie Marts

The Archived by Victoria Schwab

Fair Juno by Stephanie Laurens