Essence and Alchemy (6 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

The same fate awaited rose, neroli, and even ylang ylang, which is that rare thing, an inexpensive floral. Artificial rose oil was touted for its ease of use; it would not become cloudy in the cold, or separate into flakes. It could be relied upon to be “always of exactly the same composition,” producing “a constantly uniform effect”âunlike the varying quality of the “Turkish oils,” which required expertise and vigilance to evaluate, “in view of the attempts incessantly made with new adulterants.” An 1898 Schimmel report unabashedly extols the use of its synthetic neroli oil “in place of the French distillate”:

Our experience

32

, extending over several years, has fully convinced us that we can justly do so. Continuously handling and studying since the year 1895 a large number and wide scope of various articles of perfumery, in which our synthetic neroli has been used exclusively, we can report the fact that it has met in every respect the highest expectations and requirements. All these preparations invariably have retained their incomparably fine refreshing fragrance, stronger and better than those flavored with the natural oil. Experts to whom we have submitted these products for comparative estimation have, without exception, acknowledged the superiority of, and give preference to, those scented with the synthetic oil.

32

, extending over several years, has fully convinced us that we can justly do so. Continuously handling and studying since the year 1895 a large number and wide scope of various articles of perfumery, in which our synthetic neroli has been used exclusively, we can report the fact that it has met in every respect the highest expectations and requirements. All these preparations invariably have retained their incomparably fine refreshing fragrance, stronger and better than those flavored with the natural oil. Experts to whom we have submitted these products for comparative estimation have, without exception, acknowledged the superiority of, and give preference to, those scented with the synthetic oil.

Of course the synthetics were not of the same quality as the natural oils. Unquestionably they were cheap; they were also colorlessâin every way. They were isolated chemicals without the complexity or nuance of the naturals. They were an oxymoron, utilitarian components of a luxurious, sensual product. Having crept into the perfumer's repertoire, however, they began to dominate it and to dictate the character of fragrance blends.

The most inspired uses of the synthetics were in scents that capitalized on their brusque and one-dimensional qualities. Chanel No. 5 is the best example of this. Created by Ernie Beaux for Coco Chanel, it was the first perfume to be built upon the scent of aldehydes. It represented a complete break with the natural model, which had been kept limpingly alive by Guerlain and Coty

33

, with their flower-named scents. With Chanel, the connection between perfume and fashion was solidified.

33

, with their flower-named scents. With Chanel, the connection between perfume and fashion was solidified.

The revolution in packaging techniques ushered in by François Coty completed the birth of the modern perfume age. Born Frances Spoturno on the island of Corsica in 1876, Coty moved to France at an early age. As a youth, he became friendly with a nearby apothecary

who blended his own fragrances and sold them in very ordinary packaging. (At the time, perfumes were purchased in plain glass apothecary bottles, brought home, and transferred to decorative flasks.) Coty became obsessed with the idea of creating fragrances and presenting them in beautiful bottles. In his twenties, he went to Grasse, where he managed to work at the house of Chiris, one of the largest producers of floral essences at that time. When he returned to Paris, he borrowed money from his grandmother and built a perfume laboratory in his apartment. In 1904 he created his first perfume, La Rose Jacqueminot, which was an immediate success. In 1908 he opened an elegant shop on Place Vendôme, which was by chance next door to the great art-nouveau jeweler René Lalique. Coty asked Lalique to design his perfume bottles and found a way to mass-produce them with iron molds, having figured out that “a perfume should attract the eye as much as the nose.” He also had the ingenious idea of allowing customers to sample perfume before purchasing it. His testers, signs, and labels, all designed by Lalique, were exceptionally beautiful and helped to create Coty's extraordinary success.

who blended his own fragrances and sold them in very ordinary packaging. (At the time, perfumes were purchased in plain glass apothecary bottles, brought home, and transferred to decorative flasks.) Coty became obsessed with the idea of creating fragrances and presenting them in beautiful bottles. In his twenties, he went to Grasse, where he managed to work at the house of Chiris, one of the largest producers of floral essences at that time. When he returned to Paris, he borrowed money from his grandmother and built a perfume laboratory in his apartment. In 1904 he created his first perfume, La Rose Jacqueminot, which was an immediate success. In 1908 he opened an elegant shop on Place Vendôme, which was by chance next door to the great art-nouveau jeweler René Lalique. Coty asked Lalique to design his perfume bottles and found a way to mass-produce them with iron molds, having figured out that “a perfume should attract the eye as much as the nose.” He also had the ingenious idea of allowing customers to sample perfume before purchasing it. His testers, signs, and labels, all designed by Lalique, were exceptionally beautiful and helped to create Coty's extraordinary success.

Perfumery was now a thoroughly modern business, albeit a colorful one that still drew its share of mavericks and bohemians, thanks to its glamorous and mysterious aura as well as the potential for self-made prosperity. Among them were a fair number of women, who could make a name for themselves in this rapidly developing field without the usual constraints that limited their participation in education and professional life. An early pioneer in this respect was Harriet Hubbard Ayers (1849â1903). Born into a socially prominent Chicago family, she married a wealthy iron dealer, Herbert Ayers, when she was sixteen. After the historic Chicago fire of 1871 took the life of one of her three children and uprooted the marriage, Ayers spent a year in Paris, recovering and soaking up culture. Then she moved to New York, determined to establish her independence, and started a business selling a beauty cream called Recamier, which she claimed to have discovered in Paris, where it had been used by all the great beauties during the time of Napoleon. Genuine or not, it was an immediate success, and Ayers soon added perfumes to her line, with names like Dear Heart, Mes Fleurs, and Golden Chance. Although her family conspired to take away the business and to commit her to a mental institution, she eventually emerged to become America's first beauty columnist and the country's best-paid, most popular female newspaper journalist.

Â

Perfume vendor, era of Louis XV

Ayers's heirs were women like Lilly Daché (1893â1990), a Parisborn milliner who arrived in New York City in 1924 with less than fifteen dollars to her name and in short order owned her own business, specializing in making fruited turbans for Carmen Miranda and one-of-a-kind hats for Jean Harlow and Marlene Dietrich. In an opulent green satin showroom, she sold perfumes with names like Drifting and Dashing along with the hats.

Yet another woman captured by the economic and aesthetic lure of perfume was Esmé Davis, who was born in West Virginia to a Spanish opera singer and was herself at various times a ballet dancer who toured with Pavlova and Diaghilev, a watercolorist, a musician, and a trainer of lions, elephants, and horses. Along the way, she studied perfumery in Cairo, and when Russian friends in Paris later sent her some perfume recipes from their collection of antique formula books, she launched a fragrance line in New York with scents she christened A May Morning, Indian Summer, and Green Eyes.

Paul Poiret

34

(1879â1944) was the first couturier to create perfumes. His clientele included Sarah Bernhardt, and he employed a professional perfumer who created blendsâBorgia, Alladin, Nuit de Chineâthat ventured into exotic new territory, combining Oriental ingredients with intense and heady florals. At his fashion shows, Poiret dispensed perfumed fans, which he made sure would be used

by keeping all the windows closed. Ahmed Soliman (1906â56), known as “Cairo's Perfume King,” had a perfumery in Khan el Khalili Bazaar, Egypt's center for perfume since the time of the pharaohs. Egyptian women, however, were interested only in perfume from France, so Cairo's Perfume King made his killing off American and European tourists, to whom he marketed perfumes with appropriately exotic names: Flower of the Sahara, Omar Khayyam, Secret of the Desert, Queen of Egypt, Harem. The centerpiece of his shop was an ornate statue of the pharaoh Ramses that poured perfume from its mouth by virtue of a mechanism which had to be wound up every half hour.

34

(1879â1944) was the first couturier to create perfumes. His clientele included Sarah Bernhardt, and he employed a professional perfumer who created blendsâBorgia, Alladin, Nuit de Chineâthat ventured into exotic new territory, combining Oriental ingredients with intense and heady florals. At his fashion shows, Poiret dispensed perfumed fans, which he made sure would be used

by keeping all the windows closed. Ahmed Soliman (1906â56), known as “Cairo's Perfume King,” had a perfumery in Khan el Khalili Bazaar, Egypt's center for perfume since the time of the pharaohs. Egyptian women, however, were interested only in perfume from France, so Cairo's Perfume King made his killing off American and European tourists, to whom he marketed perfumes with appropriately exotic names: Flower of the Sahara, Omar Khayyam, Secret of the Desert, Queen of Egypt, Harem. The centerpiece of his shop was an ornate statue of the pharaoh Ramses that poured perfume from its mouth by virtue of a mechanism which had to be wound up every half hour.

Although the perfume business was booming, the direction it had taken had cut it off from its creative wellsprings. Reliance on synthetics eventually led to a shift in perfume structure and its interplay of ingredients. Most contemporary perfumes are “linear” fragrances designed to produce a strong and instantaneous effect, striking the senses all at once and quickly dissipating. They are static; they do not mix with the wearer's body chemistry, nor do they evolve on the skin. What you smell is what you get.

Â

Â

T

he decline of natural perfumery was not only a material loss but also a spiritual one. Natural perfumes evolve on the skin, changing over time and uniquely in response to body chemistry. At the most basic level, they interact with us, making who we areâand who we are in the process of becomingâpart of the story. They are about our relationship to ourselves, and only secondarily about our relationship to others. “The more we penetrate

35

odors,” the great twentieth-century perfumer and philosopher Edmond Roudnitska observed, “the more they end up possessing us. They live within us, becoming an integral part of us, participating in a new function within us.”

he decline of natural perfumery was not only a material loss but also a spiritual one. Natural perfumes evolve on the skin, changing over time and uniquely in response to body chemistry. At the most basic level, they interact with us, making who we areâand who we are in the process of becomingâpart of the story. They are about our relationship to ourselves, and only secondarily about our relationship to others. “The more we penetrate

35

odors,” the great twentieth-century perfumer and philosopher Edmond Roudnitska observed, “the more they end up possessing us. They live within us, becoming an integral part of us, participating in a new function within us.”

Natural perfumes cannot ultimately be reduced to a formula, because the very essences of which they are composed contain traces of other elements that cannot themselves be captured by formulas. Like the rich histories of their symbolism and use, this essential mysteriousness makes them magical to work with, in the sense that Paracelsus meant when he wrote, “Magic has power

36

to experience and fathom things which are inaccessible to human reason. For magic is a great secret wisdom, just as reason is a great public folly.”

36

to experience and fathom things which are inaccessible to human reason. For magic is a great secret wisdom, just as reason is a great public folly.”

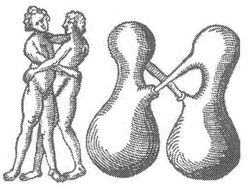

Like alchemy, working to transform natural essences into perfume is a process that appeals to our intuition and imagination rather than to our intellect. This is not to say there is no logic to it, but it is a logic of a different order. Like other creative endeavors, it is intensely solitary. The perfumer's atelier is the counterpart to the alchemist's laboratory, which was itself a mirror of the hermetically sealed flask in which the transformation of matter into spirit was to take placeâ

hermes

meaning “secret” or “sealed,” and thus referring to a sacred space sealed off from outside influences.

hermes

meaning “secret” or “sealed,” and thus referring to a sacred space sealed off from outside influences.

The hermeticism of the alchemical process consists of not just the solitary nature of the work but also its interiority. That is, it can be comprehended only by being inside it, just as we can understand love only by being in love. As Henri Bergson notes, “Philosophers agree

37

in making a deep distinction between two ways of knowing a thing. The first implies going all around it, the second entering into it. The first depends on the viewpoint chosen and the symbols employed, while the second is taken from no viewpoint and rests on no symbol. Of the first kind of knowledge we shall say that it stops at the

relative;

of the second that, wherever possible, it attains the

absolute.”

37

in making a deep distinction between two ways of knowing a thing. The first implies going all around it, the second entering into it. The first depends on the viewpoint chosen and the symbols employed, while the second is taken from no viewpoint and rests on no symbol. Of the first kind of knowledge we shall say that it stops at the

relative;

of the second that, wherever possible, it attains the

absolute.”

In alchemy, attaining the absolute meant creating the Elixir, that magical potion to defeat the ravages of time. But the process depended on the marriage of elements the alchemist could not perceive. These were the “subtle bodies

38

” that “must be beyond space and time. Every real body fills space because it consists of matter, while the subtle body is said not to consist of matter, or it is matter which is so exceedingly subtle that it cannot be perceived. So it must be a body which does not fill space, a matter which is beyond space, and therefore it would be in no time,” writes Jung, adding, “The subtle body is a transcendental concept which cannot be expressed in terms of our language or our philosophical views, because they are all inside the categories of time and space.”

38

” that “must be beyond space and time. Every real body fills space because it consists of matter, while the subtle body is said not to consist of matter, or it is matter which is so exceedingly subtle that it cannot be perceived. So it must be a body which does not fill space, a matter which is beyond space, and therefore it would be in no time,” writes Jung, adding, “The subtle body is a transcendental concept which cannot be expressed in terms of our language or our philosophical views, because they are all inside the categories of time and space.”

In other words, the alchemical quest stands for the attempt to create something new and beautiful in the world, through a process that cannot ultimately be reduced to chemistry. The elementsâor, rather, the subtle bodies in themâlearn how to marry. As Gaston Bachelard remarks, “The alchemist is an educator

39

of matter.” The experience of transformation he sets in motion in turn transforms him. As Cherry Gilchrist puts it in

The Elements of Alchemy

, “The alchemist is described

40

as the artist who, through his operations, brings Nature to perfection. But the process is also like the unfolding of the Creation of the world, to which the alchemist is a witness as he watches the changes that take place within the vessel. The vessel is a universe in miniature, a crystalline sphere through which he is privileged to see the original drama of transformation.”

39

of matter.” The experience of transformation he sets in motion in turn transforms him. As Cherry Gilchrist puts it in

The Elements of Alchemy

, “The alchemist is described

40

as the artist who, through his operations, brings Nature to perfection. But the process is also like the unfolding of the Creation of the world, to which the alchemist is a witness as he watches the changes that take place within the vessel. The vessel is a universe in miniature, a crystalline sphere through which he is privileged to see the original drama of transformation.”

Other books

Perfect Couple by Jennifer Echols

A Captive's Submission by Liliana Rhodes

Unlocked by Margo Kelly

Hurricane by L. Ron Hubbard

15 Amityville Horrible by Kelley Armstrong

The Pyramid by Ismail Kadare

La decisión más difícil by Jodi Picoult

Hammer's War 1: Forging the Hammer by James McEwan

Freedom Bridge: A Cold War Thriller by Erika Holzer

Adele Ashworth by Stolen Charms