Essex Land Girls (13 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

Left: Joyce Willsher (née Chaplin). Below: front row, left to right: Lorna Wood, Joan (not WLA), Ted, Joyce, Eileen Cradock. (Courtesy of Joyce Willsher)

I had to pick up a bicycle from the WLA offices at Writtle, but it had no handle bars or saddle, so I had to walk to Colchester to the barracks and ask the soldiers there to fix it and they did put it together, after having a giggle … I got home pretty tired. [Not surprisingly given the distances involved here, and the nature of the unmade-up roads and cumbersome nature of the Land Army issue bicycles.]

Iris Jiggens

From Stepney, Iris joined the WLA after the war (she was too young during the war years) until its demise at the end of 1950. And she left behind plenty of photographs of her years, labelled with the locations of the farms she worked on: Hawkwell, Paglesham, Hockley, Shoplands, Southminster, and ‘Stratford’s Nursery’. She obviously favoured working with horses, and kept an unusual WLA horse brass for the remainder of her life.

Iris Jiggens, née Bush (right), with beloved horses. (Courtesy of Janet Ouchterlonie)

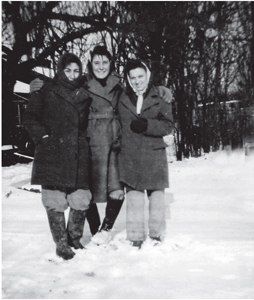

Iris (right) working in the snow. (Courtesy of Janet Ouchterlonie)

Iris’s rare horse brass. (Courtesy of Janet Ouchterlonie; image by author)

Iris working in the mud. (Courtesy of Janet Ouchterlonie)

Gladys Pudney

Gladys found herself in a very different world to that of debutantes and royalty, her previous world as a professional dressmaker. She ‘learned to prune fruit trees’ on Mr Pudney’s farm, The Orchards, at Writtle. ‘The farm had pedigree pigs, sheep and cattle [with] a herd of black and white Essex pigs. Later they kept Landrace pigs.’ There were times when the ram used to chase her, and she:

… ran for my life into the chicken house. The cattle were beef cattle. They did not even keep one milk cow. There were no horses as they had tractors … They took newly hatched eggs up to Danbury for rearing.

One of her jobs was to ‘use a little machine to check that the eggs were fertile … Fields were planted with corn and potatoes … and there was haymaking in the meadows … they also grew tomatoes which had to be kept watered using a hand pump.’ The crop from The Orchards was dramatically affected by the presence, or otherwise, of frost, varying from bumper to abysmal. ‘In a good year, the farm lorry would leave early with benches in the back to pick up women and children from the Chignal area – as many as 80.’ The farm lorry would drive up as far as Scotland to deliver produce, and Gladys herself drove a lorry to Covent Garden.

Celia Waldman

East Ender Celia cycled every day from her billet in Wakering to Potton Island. The billet was a comfortable farmhouse with no electricity but ‘it did have a bathroom, a telephone and all the food we could eat’. The journey to the island was less comfortable, with its unmade roads and the necessity to judge the tide; if you messed this up you ‘had to row across’. She ‘learnt to drive tractors and threshers, how to milk a cow and castrate a calf’ and ‘accompanied cattle from Shoeburyness train station to the island and later to the slaughter house’.

Winnie Bell

The suntan was an attraction for Winnie when it came to the haymaking, but she also enjoyed working at Rainham Market Garden with ‘lots of girls’. On the subject of threshing, ‘I had to tie up my trousers, tie up my hair, but still got smothered and often ended up with mice in my pocket’. Working out in the rain was something she ‘got used to’ as was ‘the cold tea’ provided by her landlady for lunch to accompany jam sandwiches.

Vera Pratt

Aged 17, Vera and her friend Rose arrived at Clacton Station in the summer of 1942, excited at the prospect of working in the Land Army. They walked from the station to ‘Duchess Farm, out St Osyth way, a longer hike than suspected, especially as [our] new shoes hadn’t really been broken in’. They had to keep asking for directions. People told them: ‘It’s just around the corner … just around the corner …’ Eventually, ‘a sign saying St Osyth Dairies was reassuring, but this was just a poster’. Having found the farm and met the farmer and his wife and family, Vera found herself ‘in charge of Lassie, the sow, responsible for feeding and mucking out’. She described it as a ‘lovely life’ especially as she didn’t need to get up especially early to care for her, and for the litters that came along.

At harvest time, there were other duties for Vera, including stooking the sheaves, but she also found it relatively easy to learn to plough with an old Fordson tractor. She confessed that, ‘Once, I missed a bit and there was a whole hunk of dirt not ploughed … the next morning … the farmer said “You want the spade.” “Do I?” “Yes, you missed a lot. Do it by hand this time.” It took a while but it learnt you.’ Duchess Farm kept Vera busy throughout the war years with crops such as oats, wheat and maize, a dairy herd of twenty-five cows, and brassica to be cut to feed the cattle. Sheltering in a barn from the rain was not an option, as, when she and Rose tried this in preference to cutting the kale, the farmer told them to ‘Go out and cut it! What do you think you are? Hot-house plants?’

Barbara Fisher

Barbara wrote of her six and a half years’ service in Essex (1943–49) as having been ‘a wonderful life’ although acknowledging that ‘no doubt distance of time has lent enchantment to my memories, the skylarks singing and the hares playing taking precedence over wet cold days cleaning machinery in a draughty barn or cutting kale covered with ice and snow on a bleak winter morning’. She also referred to Land Girls shedding tears when ‘parting from a beloved cow sent to market for one reason or another’:

Tinker and Blossom, a Clydesdale gelding and mare were very much a part of my life for several years. I remember … the joy of working with them, the challenge of using a horse hoe between rows of mangolds [

sic

] and kale seedlings, or bumping along on a hay rake for hours on end …

In those days milking machines were a modern invention and a three legged stool and bucket were more usual … [and] the Fordson tractor we had was a very simple design, no cabs to sit in or self starters … waterproofs to keep us dry and a starting handle to get us going.

Vera Osborne

Apart from reminiscences passed on to her daughter Jan (see Chapter Six), Vera also spoke, aged 79, to Tom King of the

Evening Echo

(Southend) about her life in the Land Army. The article focused on her experiences as ‘a stock-girl at Great Totham, looking after the goats, Berry, Blackberry, Bramble and Blanco’. Goat keeping was her favourite occupation and she recalls a time she had to take one of the goats, in heat, to ‘a tryst with a neighbouring billy’ travelling with her in a small car. She ‘couldn’t get the stench off [her] clothes for weeks’. On the other hand, her least favourite occupations ‘were ditch-clearance and swede-bashing in the depths of winter on Wallasea Island’ with threshing a close runner-up. This ‘was a filthy job. You came away from those machines covered in black.’ She was picked up each morning from ‘a hostel at Thundersley [the site now occupied by a school], usually in a caterer’s lorry … still wet from the market. We had to sit on sacks.’

Margaret and Mary Titterington

These were twins, who received their arm bands for four years’ continuous service in the WLA, reported in the

Essex Newman

of 30 November 1943. They lived at Althorne, near Southminster, and apparently it was difficult to tell them apart, other than by Mary’s spectacles. Brought up on their father’s farm, Margaret’s studies for her ‘Diploma in Agriculture at the East Anglian Institute of Agriculture’ came to an end at the outbreak of war when she became more hands on. Both girls worked on dairy farms in the area, with Mary working as a ‘milk recorder, measuring the differences in the yield of various herds’ which meant she visited different farms – mainly in the Ongar area – ‘on behalf of the Milk Marketing Board, to record the weights of milk from each cow’. Because of the nature of her work, Mary progressed beyond a bicycle to a car.

Joan Holloway and Mary Davies

While on the subject of cows … the district representative for Essex (H. Vickers) wrote in the March 1943 issue of

The

Land Girl

about these two local girls. They were from London and had arrived in Essex two years before, ‘not knowing one end of a cow from the other … today Mary has charge of 25 Friesian cows, one bull and several calves and heifers, her favourite being named The Queen of the Herd’. As for Joan, she had the experience ‘of being picked up by one jealous cow and thrown on to the back of another. This cow would sleep, and snore, during milking but at the same time did not seem to like Joan making a fuss of any other cows.’

Diana Thake

This Land Girl worked at Woodredon Farm (Waltham Abbey). Owned by Sir Fowell Buxton, it ‘produced milk, potatoes and corn, with the milk being taken to Kensington six days a week by the estate chauffeur …’ As well as food production, the estate had a herd of around fifty cattle:

We got used to the hard work and had plenty of laughs … we ploughed and rolled the land, reaped, hoed, hedged and ditched, tossed the hay, pitched, stacked and stooked the sheaves of corn, in the wind and rain. There were tractors but a lot of the work was done with horse and cart … we would take it in turn to ride the horse home after raking … there was one period during the war when we tried to milk the cows three times a day, but it didn’t last long. It was too much for the cows.