Essex Land Girls (2 page)

Authors: Dee Gordon

Employment for Winter Evenings [Suggestions for ‘little clubs’ including amateur theatricals].

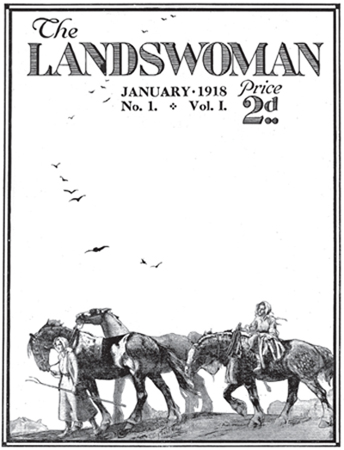

Cover of

The Landswoman

, January 1918. (Courtesy of Stuart Antrobus and

www.womenslandarmy.co.uk

)

The Knitting Club [Khaki wool offered at 5

s

per lb].

Notes and Queries Column [Any questions regarding farm work].

Competitions [Essays mainly, the first being ‘How to Cure Chilblains’, with five prizes of 1

s

each on offer].

Finally, I know just how lonely and how dull it is during these long winter evenings, miles away from everywhere, and I want you to understand and to feel that there is someone here in London at Headquarters, who is waiting to hear all about it, and who really means to help. Don’t forget! I shall expect lots and lots of letters, and by return of post. Your friend, THE EDITOR

There were plenty of advertisements in

The Landswoman

for suitable clothing – apart from adding to your uniform at Harrods and Harvey Nichols in London, you could send off 20

s

(carriage paid), for

‘field boots’ with ‘high uppers’, which were watertight and made of extra stout leather of ‘magnificent quality of hide’ from Ernest Draper & Co.’s ‘All British’ works in Northampton.

The basic uniform was free, and practical rather than stylish, incorporating a long, rubberised waterproof jacket and wide-brimmed sou’wester style hat, as well as those heavy duty boots. The Board of Agriculture advised a skirt ‘fourteen inches from the ground’, which was a relief to one anonymous poet in an issue of

The Landswoman

, who wrote that:

All can see that to work in a skirt

Is to gather up masses of dirt …

Not to mention that glimpses of hardworking ankles during the early part of the twentieth century were regarded as shocking. However, Land Army workers soon adopted the more practical option of breeches, which also gave the girls a sense of belonging and formality. Green armlets were added to the uniform of any WLA girl who had served thirty days or more during the war, with a certificate in appreciation of their work ‘truly serving’ their country, on a par with ‘the man who is fighting in the trenches’.

As more foods became restricted or unavailable and rationing kicked in, the role of the WLA became more important and widely recognised. These were girls out in all weathers, working long hours, cultivating crops – especially root crops with their high calorific value for humans and animals – and providing fodder for huge numbers of war horses.

Grassland was brought back into cultivation, and the government could step in to sort out badly run farms. Approaching 2 million acres of grassland were ploughed in order to grow wheat in one year alone (1917–18), and literally millions of tons of hay were made, mostly by hand, during the course of the war.

The WLA was disbanded in November 1919, as shipping food to Britain was once again re-established. The early proponents were awarded ‘Good Service’ medals or ribbons upon demobilisation, and fifty-five WLA members were awarded the Distinguished Service Bar.

A scheme had been advertised in

The

Landswoman

during its last few months, whereby, through saving 1

s

per week for six months, the girls would be able to afford a demob outfit, so many having parted with their civilian clothes. They returned to a brave new world, saddened by its losses, but looking forward to its gains. The vote had been secured for some women over 30 years old in January 1918, and Prime Minister David Lloyd George promised that the women’s contribution on the nation’s farms would not be forgotten. A fact which led some to say that women were only given the vote as a ‘thank you’ for their work in the fields and factories during the Great War.

The First World War in Essex

The ‘War Ag’

War Agricultural Committees were devised during the First World War, although they were far less effective than during the Second World War, by which time many lessons had been learned. The Essex Women’s War Agricultural Association (EWWAA) was inaugurated in February 1916, a month after Miss Courtauld (from the fabric family) and Lady Petre of Ingatestone Hall had been co-opted on to the all-male ‘War Ag’ (War Agricultural Committee). While this may seem a little late in the day, the whole country had been banking on an early end to the war, a hope which was finally abandoned.

By March 1916, branches of the EWWAA were set up around the county, with the one at Tendring holding an early meeting at Colchester Town Hall, presided over by Lady Byng. She explained that in each village, a registrar would be appointed to ensure that any leavers would be immediately replaced, and to ‘induce the women to work on patriotic lines and encourage thrift’ (according to the

Chelmsford Chronicle

of 24 March).

A meeting of the War Agricultural (Executive) Committee in June 1916 referred to a figure of some 3,500 women having registered, with 500 placed with farmers, although a later meeting suggested a shortage still in Orsett and some other districts. Miss Courtauld expressed an interesting opinion at a meeting towards the end of 1916: she felt that if ‘better educated’ women took up milking and other farm work, then labourers’ wives would be more willing to do the same!

The committee minutes, held in the Essex Record Office, reveal that by June 1916, local recruits included seventy dairymaids, 117 fruit farm workers, twenty-six gardeners and fourteen pea pickers. The minutes also reveal that farmers needed some encouragement to employ women, and they were expected to provide tools and equipment for their use. There were also difficulties finding suitable accommodation for female workers.

Essex, an arable area, had been growing more acres of wheat than any other county for several years, with 30,000 acres more corn than pre-war; and, additionally, meetings of the Essex War Agricultural Committee confirmed the importance of the potato crop. At one of their meetings in April 1918 (reported in the

Essex Newsman

), it was stated that about 29,000 acres had been ploughed of the 62,000 asked for, with proposals to ‘take in hand some large uncultivated blocks of land that were practically derelict’. The committee agreed that permits should be granted to enable a portion of the farmers’ barley to be consumed by agricultural stock, particularly pigs, although this would be dependent on the harvest, and reference was made to the 1,100 German prisoners of war working on the land in Essex, in many cases alongside the WLA.

The EWWAA did try and help the Essex members of the WLA in a number of ways – pushing for cheap train fares and for the supply of uniforms, for example, with some success. Free uniforms and free rail travel were offered by 1917 to those who signed on for six months or more. At least the recruits did not feel obliged to buy their uniforms in Harrods as the WNLSC (Women’s National Land Service Corps, the WLA’s predecessor) members had done, and many of them took to their bicycles – again, not easy with long skirts.

The uniform of the First World War, when available, was not stylish but it was practical – rubberised waterproof jacket, wide-brimmed hat, breeches or jodhpurs, boots and leather gaiters. One of the association’s many reports from the Uniform Department announced that 1,082 pairs of boots were sent out in 1918. The general reaction to the uniform from the farming community was summed up by a cartoon in

Punch

in May 1917, depicting a cowman and a member of the Land Army, the cowman saying, ‘you get behind that there water butt. Mebbe cows won’t come if they see you in that there rig.’

First World War recruiting poster. (Author’s collection)

At an EWWAA meeting held in London in September 1917, Lady Petre proudly stated her belief that Essex alone had started providing rest rooms which could be developed to incorporate social purposes, introducing a ‘corporate spirit of esprit de corps’. Selection and hostel committees had been inaugurated and an appeal was launched for ‘gramophones, music or books for the girls’ entertainment’. Just two months later, a photo appeared in the

Southend, Leigh & Westcliff Graphic

depicting ‘women land workers’ leading a horse-drawn cart laden with sheaves of corn, at the Lord Mayor’s Show in London.

At the end of 1918, another meeting of the EWWAA refers to 275 girls having been trained in Essex since the April meeting, with 277 now in employment. Six ‘motor tractor drivers’ were also employed locally, and six had been ‘trained as thatchers’. Six training centres had been established around the county, the most recent at Layer-de-la-Haye, and there were also five practice farms, one ‘gang hostel’ (for billeted girls) and one probationary training centre. A Mrs Tennant was now in charge of outfitting the Land Army Girls, and Miss Tritton had been appointed Welfare Supervisor. The director of the women’s branch of the Board of Agriculture, Miss Talbot, spoke of working against difficulties and prejudices to become one of the show counties, with regard to both the work and the care taken of the girls, with Essex showing the way in the welfare of land workers. A fine, healthy and ‘generally happy’ body of young women workers were likely to be required after the war in the production of food, and the movement had given women a chance ‘to show their usefulness and adaptability’. Notably, the Agricultural Labourers’ Union was starting to attract female members.

Food shortages extended to troops as well as the general public, and it was not unknown for uniformed troops to visit Essex farms to purchase fodder for their horses and food for their own cookhouse. A ‘National Farm Survey’ was carried out to check how farmers were coping, and Warren Farm in Writtle, owned by Mr Christy, was found to be ‘deficient’ in a 1916 survey reproduced in

Heritage Writtle

. This shows that just eight men were responsible for 326 acres, sixty-two cows, ninety-five sheep, thirty-eight pigs and sixteen horses – no wonder women workers were needed.

Although there was a shortage of male agricultural workers, not all farmers were happy at replacing them with female workers. One farmer, Mr A.B. Markham of Laindon, featured in the

Essex Newsman

(21 October 1916) because ‘one of the men for whom he had previously obtained exemption [i.e. from service] on condition that women were brought in to help had refused to work with women and had left him’. He had not been able to ‘get another man’ and ‘had therefore given up one milk round’, losing income as a result.

Quite a number of Essex mansions gave employment to Land Girls, thanks to a shortage of gardeners during the years of the war. One of these was Copped Hall in Epping, belonging to the Wythe family. Sylvia Keith’s definitive account (in

Nine Centuries at Copped Hall

) refers to the Wythes getting ready for church on Sunday morning, 6 May 1917, when a fire broke out, though it was ‘not taken seriously’ to start with. Various causes have been attributed – an electrical fault, or a discarded cigarette. Whatever the cause, far less men than before the war were available to manoeuvre and operate the horse-drawn fire engine and screw together the sections of hose, delivering a rather paltry ‘solitary jet of water’, so necessitating staff, gardeners, keepers – anyone and everyone – to assist in salvaging what they could until fire brigades from other local areas could come to their assistance. Luckily, Land Girls Alice Grimble and ‘Miss N. Deary’ were on hand to help. Mrs Grimble described the glass ‘melting’ in one report, running down the windows ‘like tears’. She was ordered to save ‘rare books and heirlooms’ in the library and climbed from shelf to shelf, throwing what she could down ‘into baskets’. The two girls were shut in another room for a time when the door jammed, and had to wait for the firemen to rescue them, a scary experience. Sadly, the building itself was almost totally destroyed.

An October 1917 issue of the

Illustrated War News

describes members of the WLA as ‘women of leisure, daughters of professional men, women who have given up lucrative employment at their country’s call, and thrown aside the frock of peace for the brown drab overalls of war’. ‘Upper-class’ ladies (in the

Downton Abbey

mould) were certainly drafted into the Land Army and often employed as grooms and stable managers at studs and racing stables, breaking and training horses for service. At the beginning of the war, paddocks at Elsenham Hall were reputedly staffed by Land Army Girls, who took on horses and mules suspended from active service for being ‘incurably vicious’. These were restored to good form and returned to the fray.