Everything Beautiful Began After (25 page)

Read Everything Beautiful Began After Online

Authors: Simon Van Booy

HENRY

: Someone else lives there.

DAD

: Henry, what’s really going on?

HENRY

: Since Rebecca died, I’ve been wandering around.

DAD

(

in background

): Some girl called Rebecca died.

MUM

(

in background

): His girlfriend?

DAD

(

in background

): How should I know, Harriet?

DAD

: Have you been working?

HENRY

: No, just thinking.

DAD

: About what?

HENRY

: Rebecca. And my brother.

Silence.

DAD

: Henry.

HENRY

: I’ve thought about it a lot.

Silence.

HENRY

: Dad?

Silence.

HENRY

: I feel okay about things now.

DAD

: I see.

Mum, in background, wants to know what he’s talking about. Dad says he’ll tell her after.

DAD

: How long do you need to get everything together?

HENRY

: About fifteen minutes.

DAD

: Fifteen days?

HENRY

: Yes.

DAD

: Send us your details a couple of days before you come, and we’ll pick you up from the airport.

Silence.

DAD

: Call us anytime, son.

HENRY

: Thanks.

DAD

: Your mother and I had no idea that someone had died.

Mum grabs phone again.

DAD

(

in background

): Harriet!

MUM

: So who was Rebecca? You never mentioned her before.

HENRY

: Someone I met.

MUM

: A girl?

Silence.

HENRY

: Yes.

MUM

: A girlfriend?

Silence.

HENRY

: I’ve just been drifting.

MUM

: Well, we’ve missed you.

HENRY

: Really?

MUM

: But you’ve been living your own life. We didn’t want to interfere.

HENRY

: I feel like I’ve come off course.

MUM

(

in background to Dad

): He feels like he’s been blown off course.

Dad takes the phone.

DAD

: Come home, son.

HENRY

: Thanks.

DAD

: Call us from the hotel with your details.

Silence.

DAD

: We had no idea your girlfriend had died and that you’d stopped working. Come home for a bit. And if you don’t want to work for a while, you have your grandmother’s inheritance to fall back on.

Next to the telephone booth is a Yamaha scooter with a ripped seat. In a nearby building someone is drilling. Buses hiss past. The light turns green, and old people drive too long in first gear. People leave the bank in a steady drip, then linger to gossip outside.

A child is styling her hair with a purple plastic hairdryer. Sheets of plywood long forgotten rot against the metal wall of a kiosk. The sidewalk is gray and dusty. The road barriers are twisted where struck by vehicles. A woman is hanging a sign in the shop opposite. It says,

mega bazaar

.

Another child with a plastic hairdryer. A man in slippers smokes and reads the paper standing up. A teenager on a scooter. Her T-shirt says,

i love you, but

. In the distance, a bare scorched mountain.

Another child with a plastic hairdryer.

Men in old polo shirts spinning beads over their hands. The men hover around you. They have nothing to do and want to talk. It passes the time. Gives them something to think about later at the kitchen table with the lights on.

You have felt alone too.

Standing at the intersection of Leoforos Iroon Polytechniou and Charilaou Trikoupi, you decide that to overcome loneliness you must conquer your fear. Once it was fear of rejection; now it is fear of the past.

When Athens was under Turkish rule, Piraeus was empty, uninhabited, a blowing stretch of dusty land, dotted with ruins at the edge of a city. Even the name had been forgotten. But slowly it rose again from the ashes and filled with people, cars, boats, bicycles; bustling markets of fish and meat; hard lemons and their green drying leaves; old men with newspapers; and the occasional table of plastic hairdryers with little hands reaching.

It’s quite clear how your life will continue from this point on. So predictable, in fact, that you envision it from a street corner in Athens.

You imagine setting the bag of fish down somewhere near the phone booth and then going home to Britain.

There you will survey the artifacts of your childhood and decide on a new course for your life.

You can already feel it happening.

Months of quiet despair.

Then applying for jobs at museum offices in London.

You’ll have to get a flat.

Dad will take your stuff in the Land Rover.

Mum will fill a box of cans from the kitchen cupboard, a few of which will be out of date.

Dad looking for coins to put in the parking meter. People walk by and see a car full of things to be unloaded. You’ll have to get used to the city again—get used to being watched again.

Then dinner in the empty flat from a nearby takeaway with your parents. The smell of fresh paint.

Your father’s usual enthusiasm. Your fishing rod in the corner for good measure.

You will work quietly in your first year and make some friends.

At night you will mostly come home and watch films on television. On warm afternoons you’ll go to the pub with colleagues and watch wasps linger over the glasses.

People at work will see you as a shy young man of about thirty.

Someone will have a secret crush on you.

Nobody will know that you’re really an old man, a ruined man with a sadness so deep it’s like unbreakable strength. And when someone comes to you with bad news—their grandparent, an aunt with cancer, a cousin suddenly one morning in a car—you’ll have to pretend any reaction beyond indifference.

You will eventually meet a girl in London—probably someone called Chloe or Emma—maybe at a summer pub or waiting for the bathroom at Foyles Bookshop on Charing Cross Road. She will introduce herself. A bit older than you. It’s too late to be shy. You will talk about this and that. She will love books—went to Cambridge, but so many years ago now. She’s lonely. She’ll sense your depth without knowing you. It will get late without either of you realizing. You’ll offer to walk her somewhere. She’ll stop at Marks and Spencer for her dinner. You will watch her pick things from the shelves and put them into her basket. You will carry her basket. She will ask if you’ve eaten, and you’ll say no. You will make love to her before dinner and then after. It will be the first of many nights. The mothers will want to know everything quickly. Houses will have to be tidied up. You’ll be welcomed by her group of friends, who are witty and sweet but talk about you when they’re drunk.

Soon enough you’ll be visiting her parents the day after Christmas. You will laugh at her father’s jokes, look at pictures of her as a child as they sigh; everything is happening so quickly. Her younger brother will smoke dope in his room and give you some. He’ll tell you that you’re cool and then ask what London is like—maybe even admit to you he’s gay, even if he isn’t.

She will kiss her parents good night as you wave to them sheepishly from the doorway. Then in the car she’ll tell you the nice things her father said. You’ll both laugh.

For her—it’s the love affair you’ve already had.

In five years you will have your first child, a girl. You will love her immediately. She will giggle at bright colors and movement, random things too—like bread falling off the counter. Later, she will run from you naked—refusing to get dressed. She will cry when you drop her off at school, then cry when you pick her up. She will scream for you in the night and not know why. You will get promoted and oversee a big exhibition that makes the papers. You will recognize a few of Chloe or Emma’s friends from the society pages in

Tatler

. You will choose Chloe or Emma’s Christmas presents carefully from Liberty of London.

Also: romantic weekends in the Cotswolds or a long weekend in New York.

Years later, you’ll have a fling with someone much younger, but it will only deepen your devotion to Chloe or Emma as you realize what a friend she’s become over the years.

George will have started drinking again and die of something alcohol-related in a place like Malta or Corsica. You won’t even know. His apartment will be cleared by the landlady’s son, and his books and manuscripts sent to the dump.

Then one day, your teenage daughter on a long car trip will lean forward between the seats and ask if you remember falling in love for the first time.

Chloe or Emma will reach over and squeeze your hand—her greatest moment of vulnerability and she doesn’t even know.

A few hours after you return to your hotel from the museum in Piraeus, the police show up again. The receptionist calls you to come down.

When the elevator doors open the police have already gone.

The receptionist hands you a book with most of the pages ripped out.

“What’s this?”

“I don’t know,” the receptionist says and then tells you what the police told her. The neighbor who called them later realized she had seen you before—visiting the girl who once lived there. And that perhaps you were looking for the book she had found.

“But how did she get it?”

“I don’t know,” the receptionist says.

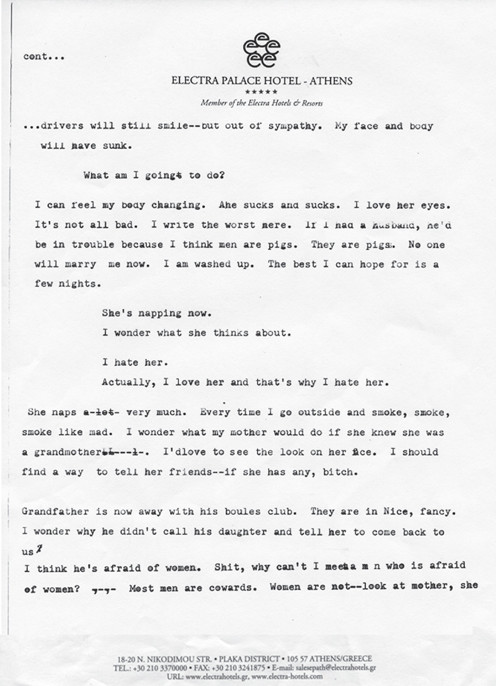

You open the book in the elevator. There’s writing inside. It’s in French. It looks like the hand of a teenage girl.

You run a bath and take the book in with you.

Standing naked between the clear water and the mirror, you recognize the handwriting. You sit on the side of the bathtub. It’s definitely hers, you’re sure of it.

The book smells like wood. There is dust in all the pages.

There are no dates, only entries—small paragraphs of text scribbled across three pages.

It’s slow reading. Some words you don’t know. You need a French dictionary.

After your bath, you thread paper into your typewriter and write out the parts you can read. You look up at the clock’s quiet announcement of 4:16.

Everything you thought you knew about Rebecca has been called into question by these pages, these few sentences in a diary.

You feel deceived by fragments of a language you can barely read.

The truth seems simple and cruel: she hadn’t trusted you enough to tell you the secret these pages expose. And now, your memory of her—like some portrait of a child, unaffected by time and death, has suddenly aged before your eyes and succumbed to ruin.

The memory you had been living to preserve is a fake.

And your greatest joy, your defining moment of victory, and your savage, unending grief have been the result of nothing more than an affair—a childish, Greek affair.