Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (50 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

2.

Examine all the skin for a discoid erythematous raised rash (

Fig 9.6

), a photosensitivity rash and a classical malar rash (

Fig 9.5

).

FIGURE 9.5

Malar rash in SLE (face). B J Beck. Mental disorders due to a general medical condition.

Comprehensive clinical psychiatry

. Ch 21. 257–281. On-line Archives of Rheumatology, 2008, with permission.

FIGURE 9.6

Discoid lupus rash. Note sparing of the proximal interphalangeal joints, a typical SLE feature. M Dall’Era.

Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology

. Saunders, Elsevier, 2013, with permission.

Remember that discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) occurs in 20% of SLE patients. This disfiguring skin disease leads to permanent hair loss with telangiectasia, scaling, circular erythematous lesions and follicular plugging. There is often destruction of skin appendages. DLE can occur without other features of SLE.

3.

Look at the hands for vasculitis, which can produce nail-fold infarcts and ischaemia or gangrene, and rash (e.g. photosensitivity, diffuse maculopapular rash).

4.

Look for Raynaud’s phenomenon and arthropathy (fusiform swelling of the PIP joints or synovitis, possibly in a rheumatoid arthritis distribution – 10% develop swan neck deformity and ulnar deviation of the fingers). This non-erosive arthropathy is referred to as Jaccoud’s arthritis.

5.

Look at the forearms for livedo reticularis and purpura as a result of vasculitis or thrombocytopenia. Test for proximal myopathy caused by actual disease or secondary to steroid treatment.

6.

Inspect the head. Look for alopecia. Lupus hairs are characteristic: they occur above the forehead and are short, broken hairs that grow back quickly after hair loss (except in patients with DLE).

7.

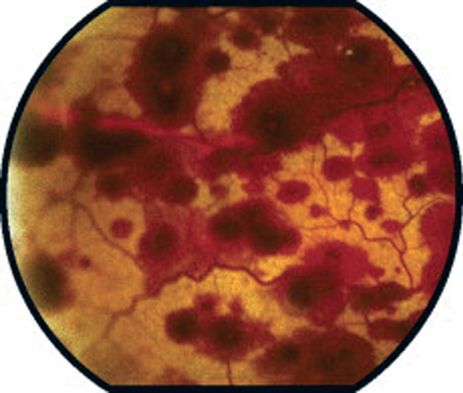

Look at the eyes for keratoconjunctivitis sicca and for pale conjunctivae owing to anaemia, and look at the fundi for cytoid lesions (hard exudates secondary to vasculitis).

FIGURE 9.7

Cytoid lesions in fundi. This patient also has a hemorrhagic fundus from SLE. L Yannuzzi.

The retinal atlas

. Ch 6. Elsevier 2010, with permission.

8.

Look in the mouth for ulcers and infection. Note any facial rash (butterfly photosensitivity rash (30%), discoid lupus or diffuse maculopapular rashes). Feel the cervical and axillary nodes.

9.

Examine the chest. In the cardiovascular system, note signs of pericarditis or murmurs (Libman-Sacks endocarditis is very uncommon).

10.

In the respiratory system, note signs of pleural effusion, pleuritis, interstitial lung disease or atelectasis.

11.

Examine the abdomen for splenomegaly (usually mild) and hepatomegaly. Feel for abdominal tenderness.

12.

Examine the hips for signs of aseptic necrosis.

13.

Examine for proximal weakness in the legs, cerebellar ataxia, hemiplegia and transverse myelitis. Assess mental status (cognitive changes, even psychosis).

14.

Also examine for neuropathy (mainly sensory) and mononeuritis multiplex, as well as thrombophlebitis and leg ulceration.

15.

Look at the urine analysis for evidence of renal disease (haematuria and proteinuria).

16.

Take the blood pressure (it may be elevated in renal disease). Also look at the temperature chart for fever, indicating active disease or secondary infection.

Investigations

1.

Diagnosis depends on a combination of the symptoms, signs and laboratory test results (see

Tables 9.8

,

9.9

and

9.12

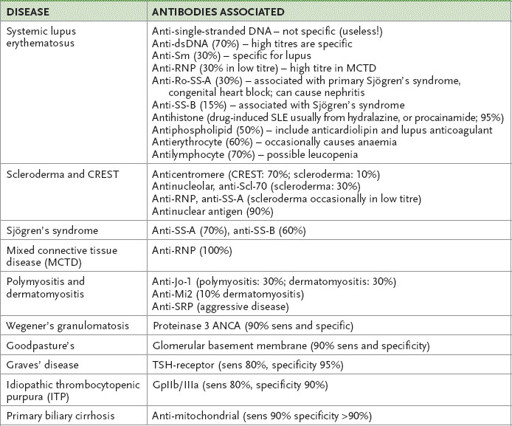

). Almost all cases are ANA-positive, which is very sensitive but not specific (if ANA-negative, check SSA/SSB). Very specific tests for SLE are anti-dsDNA (including titre, 100% specific) and anti-Sm (positive virtually only in SLE).

Table 9.12

Antibodies associated with connective tissue and other auto-immune diseases

CREST = calcinosis cutis; Raynaud’s phenomenon; (o)esophageal involvement; sclerodactyly; telangiectasia; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; ANCA = Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; Sm = smith; SRP = signal recognition protein; sens = sensitivity

2.

Patients who do not fit the criteria may have another connective tissue disease. Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is suggested by the overlapping clinical features of scleroderma, polymyositis and SLE and the presence of characteristic antibodies to nuclear ribonucleoprotein (nRNP), which is one of the extractable nuclear antigens. Anti-nRNP is present in high titre and produces a speckled pattern on fluorescent antibody testing in patients with MCTD. When these patients are followed for many years, they may start to resemble patients with progressive systemic sclerosis or SLE, or may continue with a relatively undifferentiated connective tissue disease.

3.

MRI scans and lumbar puncture (increased protein and mononuclear cells) may be indicated if central nervous system lupus is suspected. Central nervous system symptoms often correlate poorly with serological measures of the activity of the disease. Do not miss bacterial meningitis in SLE.

4.

Haematological tests:

a.

Anaemia – normochromic, normocytic and related to the chronic inflammatory processes – is very common. Immune haemolytic anaemia is less common and the Coombs’ test then gives a positive result.

b.

The ESR tends to be elevated but the CRP is often normal, except during episodes of serositis.

c.

Leucopenia (especially lymphopenia) occurs in over half the patients and may be caused by antibody directed against leucocytes.

d.

The lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies, or both, are found in about 10% of cases. Characteristically, there is a prolonged partial thromboplastin time with kaolin (PTTK), which is not corrected by the addition of normal plasma. It is associated with thrombosis rather than bleeding.

e.

Thrombocytopenia occurs in 15% of cases and is associated with anti-platelet antibodies.

5.

Immunological tests:

a.

The characteristic abnormalities are the presence of autoantibodies (see

Table 9.12

). ANAs are present in 99% of cases and are usually detectable from the time of onset of symptoms. The antigens involved include single- and double-stranded DNA, SS-A and SS-B, and Sm antigen (an acidic nuclear protein). Many antibodies persist even when the disease is quiescent. Antibodies to dsDNA and Sm are the most specific for SLE and are therefore the most useful diagnostically. The latter, however, is not very sensitive.

b.

Complement abnormalities are usual during exacerbations of the disease, with a reduction in total haemolytic complement (CH50) and in the components of the classical pathway (C3 and C4). The combination of a low CH50 and normal C3 suggests an inherited deficiency of complement components and is strongly associated with SLE. The finding of high levels of anti-dsDNA and lower complement levels are usually associated with active disease and especially renal involvement.

c.

Positive rheumatoid factor occurs in 10% of cases at low titre. Skin biopsy in SLE can be helpful; positive immunofluorescence of the basement membrane in involved skin occurs in 95% of patients.

Treatment

Current work suggests that appropriate treatment to suppress exacerbations of SLE will prolong life. Many patients have mild disease without life-threatening complications. The prognosis of SLE is generally good. There is a 75% 10-year survival rate; the major causes of death are infections, renal failure, lymphoma and myocardial infarction.

1.

Arthralgias, myalgia and fever respond to rest and NSAIDs.

2.

Exposure to sunlight should be avoided and sunscreen used.

3.

Hydroxychloroquine is useful in the management of arthritis and skin rash. Annual retinal and visual field examinations must be performed in patients on this drug because of the cumulative risk of retinal toxicity.

4.

Raynaud’s phenomenon may respond to calcium channel antagonists.

5.

Steroids are indicated for central nervous system involvement, pericarditis, myocarditis, pleurisy, severe haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Use of high initial doses with gradual reduction once improvement occurs is the proper method of treatment.

6.

Hypercoagulability (thrombotic episodes and antiphospholipid antibodies) should be treated with warfarin for life, with a target INR of 2.5–3.

7.

Management of renal disease is difficult. Renal biopsy usually shows abnormalities, but often only mild changes. Virtually any type of glomulonephritis may occur. Renal biopsy is indicated early if there is any clinical or biochemical evidence of renal disease or if the urine sediment is abnormal. Four main groups of biopsy abnormalities can be identified:

•

mesangial proliferation

•

focal glomerulonephritis

•

diffuse proliferation

•

membranous proliferation.

Mesangial proliferation has the best prognosis – disease is unlikely to progress. Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis has the worst prognosis and aggressive treatment (e.g. high-dose pulse steroids plus cyclophosphamide) is recommended. Membranous proliferation has a low rate of response to treatment. SLE is not a contraindication to dialysis or renal transplant in those patients who develop renal failure, but there is a higher than average risk of graft failure.

8.

Calcium and vitamin D supplements should be offered to protect against osteoporosis. Bisphosphonates should be considered if long-term steroid treatment is likely.

9.

Azathioprine is indicated as a steroid-sparing agent. Methotrexate can also be used, particularly if arthritis is prominent.

Cyclophosphamide is a more toxic alternative. Intermittent pulses of cyclophosphamide may be helpful. These agents are particularly indicated in active glomerulonephritis.