Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (60 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

6.

Once proteinuria develops, progression to end-stage kidney disease appears inevitable over a period of about 5–10 years. The rate of progression may be modified by:

a.

control of hypertension – ACE inhibitors are the agents of choice, but it is important to be aware of the risk of hyperkalaemia as a result of hyporeninaemic hypoaldosteronism and deteriorating kidney function in patients with renovascular disease

b.

treatment of urinary tract infections

c.

dietary protein restriction

d.

possibly improving glucose control.

ACE inhibition is indicated as soon as proteinuria is detected. ARBs are an alternative for those intolerant of ACE inhibitors. ACE-I and ARB combination treatment may reduce proteinuria further, but has little additive effect on blood pressure and is associated with an increased risk of acute kidney failure. There is an increased incidence of papillary necrosis with urinary tract infection.

7.

The best form of management for end-stage chronic kidney disease in a diabetic is peritoneal dialysis and early kidney transplantation. Remember that diabetics with chronic kidney failure almost invariably also have retinopathy, which may be worsened by haemodialysis.

8.

For those with severe systemic complications or end-stage kidney disease, whole-organ pancreas (with or without kidney) transplantation is a promising therapeutic option. A number of successful kidney/pancreas transplants have been performed. Patients are generally euglycaemic without hypoglycaemic treatment. This is the treatment of choice for diabetics with kidney failure.

The pregnant patient with diabetes

Remember that blood sugar levels are normally lower in pregnancy. A woman with no diabetic history should be screened for gestational diabetes in the 24th–28th week. A 50-g glucose load is given and the blood sugar is measured 1 hour later. The normal result is <7.0 mmol/L. Between 7.0 and 7.8 mmol/L is borderline (repeat) and ≥7.8 mmol/L means that a formal 75-g glucose tolerance test is required: a fasting level of ≥5.3 mmol/L and a 2-hour level of ≥8.6 mmol/L indicates gestational diabetes mellitus.

1.

Insulin requirements vary during pregnancy owing to the effects of human placental lactogen (HPL). In the first trimester, insulin requirements usually remain unchanged or may decrease, but in the second trimester some increase in insulin requirements occurs owing to rising HPL levels. By the third trimester insulin requirements are usually at least 50% higher than before pregnancy, but after delivery there is a dramatic decrease in insulin requirements.

2.

Blood glucose control should be improved as much as possible before conception in a diabetic woman wanting to undertake pregnancy. Haemoglobin A

1c

should be normalised, as strict metabolic control at the time of conception has been shown to prevent the otherwise increased incidence of congenital malformations in the offspring of diabetic mothers. The complications of poor control seen in the infant are:

a.

congenital malformations such as spina bifida (incidence about 6%, double the normal rate)

b.

macrosomia

c.

intrauterine fetal death in the later stages of pregnancy

d.

hypoglycaemia after delivery

e.

complications related to immaturity (e.g. respiratory distress syndrome, hypocalcaemia, jaundice).

3.

Use of home blood glucose monitoring, with testing of both pre- and postprandial glucose levels, is essential. Strict glucose control must be maintained during labour and delivery. Paediatric services and a neonatal intensive care unit should be available. Remember that statins, ACE inhibitors and ARBs

must

be ceased in pregnancy.

CHAPTER 11

The renal long case

When the patient dies the kidneys may go to the pathologist, but while he lives the urine is ours.

Thomas Addis (1881–1949)

Chronic kidney disease (chronic renal failure)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) by itself is not a particularly common subject for the long case. However, it is a difficult and important topic and kidney disease is often present in that very common long case, the obese diabetic with hypertension and vascular disease. Keep in mind the current CKD classification (

Table 11.1

). The patient will usually know that he or she has renal disease. Methodical questioning to establish the diagnosis, cause, management and complications is necessary.

Table 11.1

Stages of chronic kidney disease

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION | GFR (ML/MINUTE) |

| 1 | Kidney damage but normal GFR | >90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage and mild GFR reduction | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderate reduction in GFR | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severe reduction in GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Kidney failure | <15 |

GFR = glomerular filtration rate.

The history

QUESTIONS REGARDING SYMPTOMS, DIAGNOSIS AND AETIOLOGY

1.

The earliest symptoms of renal failure include nocturia, lethargy and loss of appetite. Patients are sometimes diagnosed following an episode of haematuria or loin pain. The first episode of overt renal failure may have been precipitated by a further insult, such as use of NSAIDs, radiocontrast injections, infection, ACE inhibitors or AR blockers (if bilateral renal artery stenosis), dehydration or anaemia. Asymptomatic proteinuria or haematuria may have been detected during a routine or insurance medical examination or during pregnancy.

2.

Glomerulonephritis

(

Tables 11.2

and

11.3

). Determine whether there is a history of proteinuria, haematuria, oliguria, oedema, sore throat, sepsis, rash, haemoptysis or renal biopsy. Ascertain treatment details (e.g. antihypertensives, immunosuppressives, anti-platelet therapy, dialysis).

Table 11.2

The nephrotic syndrome

Note:

Renal vein thrombosis is a complication and rarely a cause of the nephrotic syndrome.

Table 11.3

Classification of glomerulonephritis

2.

Diabetic nephropathy

. Ask about other complications and therapy. An ACE inhibitor or AR blocker is preferred for all cases with diabetic nephropathy.

3.

Polycystic kidneys

. Ask about family history, how the disease was diagnosed, haematuria, polyuria, loin pain, hypertension, renal calculi, headache, subarachnoid haemorrhages and visual disturbance (intracranial aneurysm). Also ask about deafness and a history of persistent haematuria (hereditary nephritis – Alport’s syndrome).

4.

Reflux nephropathy

. Ask about childhood renal infections, cystoscopy, operations, treatment (e.g. regular antibiotics) and enuresis.

5.

Analgesic nephropathy

. Ask about the number, type and duration of analgesics consumed, urinary tract infections, hypertension, haematuria, gastrointestinal blood loss, nocturia, renal colic (sloughed papillae, stones), transitional cell cancer and anaemia. This cause of renal failure is now very uncommon following the withdrawal of compound analgesics containing aspirin and phenacetin, but some of these patients are still available (alive).

6.

Hypertensive nephropathy

. Ask how the disease was diagnosed, duration and control of hypertension, treatment and compliance with medication, angiography, family history.

7.

Connective tissue disease

. Think especially of systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma.

8.

Find out whether the patient is aware of the long-term prognosis. If he or she is not on dialysis yet, has this been discussed? Is the patient likely to be eligible for dialysis or the transplant list?

9.

Ask when the underlying condition was diagnosed and how it is being treated. The progression to end-stage kidney disease may be rapid or very prolonged.

QUESTIONS REGARDING MANAGEMENT (

Table 11.4

)

Table 11.4

Principles of management of CKD

1.

Conservative management

a.

Ask about follow-up, medications, diet, salt and water allowance, investigations performed (particularly renal biopsy) and whether erythropoietin has been given subcutaneously in an attempt to elevate the haemoglobin.

b.

Has the patient been advised to restrict protein intake? There is controversy about the value of protein restriction in delaying end-stage renal failure. Patients with nephrotic syndrome should be much less restricted. The concern about protein restriction is that it leads to more rapid loss of muscle mass without much delay in end-stage renal failure.

c.

What effect have the disease and the dietary and other restrictions had on the patient’s quality of life and his or her family?

d.

Certain treatments can slow the progression of glomerulonephritis to end stage renal failure. Ask about specific treatment including steroids and other immunosuppressants, treatment of hypertension and advice about smoking cessation and avoidance of nephrotoxins.

2.

Dialysis

(

Table 11.5

). Ask about haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, including where performed, how often, how many hours per week, relief of symptoms with treatment and subsequent complications. Also ask about shunts, other operations (e.g. renal tract operations, parathyroidectomy) and medications taken.

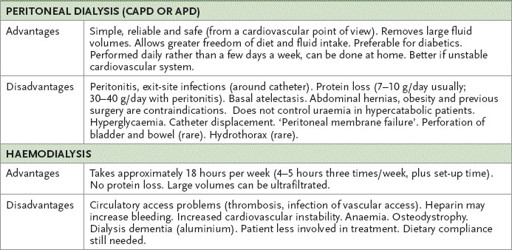

Table 11.5

Dialysis