Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (61 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Note:

Mortality from dialysis is caused by myocardial infarction (60%) or sepsis (20%) in most cases. Acquired cystic disease in native kidneys may occur; <5% are malignant. Arthropathy and carpal tunnel syndrome may occur in long-term dialysis patients owing to amyloid (beta

2

-microglobulin) deposition.

APD = automated peritoneal dialysis (exchanges done at night); CAPD = chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

3.

Transplant work-up and management

. Ask when and how many, whether living relative or cadaver, postoperative course, improvement, symptoms since transplantation, medications, follow-up and long-term complications (e.g. neoplasia, steroid complications).

4.

Bladder management for reflux or neurogenic bladder

.

5.

Social arrangements and ADLs

. Ask about employment, the family’s ability to cope, travel, sexual function and financial situation.

QUESTIONS REGARDING COMPLICATIONS

1.

Conservatively treated patients

. Ask about symptoms of anaemia, bone disease, secondary gout or pseudo gout, pericarditis, hypertension, cardiac failure, fluid overload, peripheral neuropathy, pruritus, peptic ulcers, impaired cognitive function and poor nutrition. Have the doses of renally excreted drugs given for other conditions been reduced? Remember that although most drugs that require a loading dose are begun at their usual dose (and then continued at a reduced maintenance dose), digoxin, which has an altered volume distribution, must have its loading dose reduced.

2.

Dialysis patients

. Ask about shunt blockage and access problems, infection, pericarditis, peritonitis, etc.

3.

Transplant patients

. For patients with recent transplants ask about graft pain or swelling (failure of graft function, rejection), infection, urine leaks and steroid side-effects. For those with long-term renal grafts, ask about serum creatinine levels, proteinuria, recurrent glomerulonephritis (dense deposit disease), avascular necrosis, skin cancer and reflux nephropathy. Find out about compliance with drugs and whether the patient knows about rejection episodes and treatment (e.g. with muromonab–CD3).

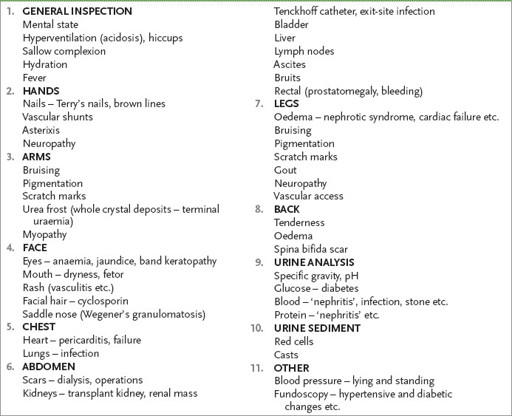

The examination (see

Table 11.6

)

A complete physical examination is always essential. Look particularly for the following.

Table 11.6

Chronic kidney disease (renal failure)

1.

General appearance – mental state, hyperventilation, Kussmaul’s breathing, hiccupping and the state of hydration.

2.

Hands – nails for white transverse opaque bands or lines in hypoalbuminaemia; a brown arc near the ends of the nails (Terry’s nails – see

Fig 11.1

) in renal failure. Also palmar crease pallor, vasculitis, vascular shunts at the wrist, scars from old vascular access sites, asterixis and peripheral neuropathy.

FIGURE 11.1

Terry’s nails in chronic kidney disease. There is proximal pallor with distal brownish color in a patient with chronic renal failure. G M White, N H Cox (eds).

Diseases of the skin: A color atlas and text

, 2nd edn. St. Louis, Mosby, Elsevier, 2006, with permission.

3.

Arms – bruising, pigmentation, scratch marks, subcutaneous calcification, myopathy, fistulae and skin cancers, especially squamous cell carcinomas.

4.

Face – eyes for jaundice, anaemia and band keratopathy (caused by hypercalcaemia); mouth (dry, fetor); rash (e.g. SLE); and a Cushingoid appearance.

5.

Chest – pericardial rub, cardiac failure, lung infection, pleural effusion and venous hum (shunt). Presence of central venous catheter for access to dialysis.

6.

Abdomen – palpable kidney, scars (owing to dialysis or transplants), renal artery bruit (a systolic bruit, or occasionally a systolic–diastolic bruit in the upper abdomen, suggests possible renal artery stenosis), bladder enlargement, rectal examination (for prostatomegaly, urethral mass and signs of blood loss), nodes (lymphoma, cytomegalovirus or other infections if the patient is immunosuppressed), ascites (dialysis or other causes), and femoral bruits and pulses.

7.

Urine – for blood, protein, specific gravity, pH, glucose, urine microscopy and examination of the urinary sediment for casts.

8.

Legs – oedema, bruising, pigmentation, scratch marks, peripheral neuropathy, vascular access and myopathy.

9.

Back – bone tenderness and sacral oedema.

10.

Blood pressure lying and standing. Fundoscopy.

Investigations

1.

Determine renal function:

a.

glomerular filtration rate (GFR) – creatinine clearance (creatinine clearance levels of <10 mL/min are considered indications for dialysis) and plasma creatinine/urea level; the GFR is routinely calculated by laboratories and the patient may know these results

b.

tubular function – plasma electrolyte levels, urine specific gravity and pH, glycosuria, serum phosphate and uric acid, aminoaciduria, serum calcium and plasma albumin levels

c.

urine analysis and urinary protein excretion (protein-to-creatinine ratio)

d.

others if necessary – CT scan for renal artery stenosis or urinary tract obstruction.

2.

Determine renal structure:

a.

ultrasound – renal size and symmetry, signs of obstruction; small kidneys suggest chronic disease

b.

plain X-ray film of the abdomen (KUB – kidneys, ureters, bladder)

c.

intravenous pyelogram (IVP) under good hydration (but avoid in patients with diabetes mellitus or myeloma, or when the creatinine level is >150 mmol/L – it has largely been replaced by less invasive tests)

d.

CT scan – same restrictions as for IVP if contrast is to be used; hydration with IV saline does offer some renal protection; the use of oral

N

-acetylcysteine before and after the use of contrast material is of uncertain benefit

e.

cystoscopy and retrograde pyelography

f.

other – renal artery Doppler study, CT renal angiography.

3.

Consider investigations aimed at assessing the widespread effects of renal failure – blood count; serum ferritin and iron saturation level; midstream urine examination; calcium, phosphate and alkaline phosphatase levels; parathyroid hormone level; nerve conduction studies; arterial Doppler studies.

4.

Decide whether there are features that favour chronic over acute kidney disease: nocturia, polyuria, longstanding hypertension, renal osteodystrophy, peripheral neuropathy, anaemia, hyperphosphataemia and hyperuricaemia. The differentiation of acute and chronic renal failure is also aided by determining kidney size. They are usually small in chronic kidney disease, but the exceptions to this rule include:

•

diabetic nephropathy (early)

•

polycystic kidneys

•

obstructive uropathy

•

acute renal vein thrombosis

•

amyloidosis

•

rarely other infiltrative diseases (e.g. lymphoma), which can all produce chronic renal failure but maintain normal kidney size.

In general, however, kidneys enlarge or maintain normal size in acute renal failure and are small in chronic renal failure.

5.

Look for anaemia and the presence of burr cells in the peripheral blood film, which are usually indicative of chronic kidney disease but may occur in acute renal failure (e.g. in SLE), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the haemolytic uraemic syndrome.

6.

Always ask about previous urine analyses, such as insurance examinations, in which proteinuria may have been detected and followed up, thus giving a clue about chronic glomerulonephritis.

7.

Consider investigations aimed towards the likely underlying disease process – measurement of antinuclear antibody; hepatitis B surface antigen; hepatitis C; HIV; complement; immune complexes; immunoelectrophoresis; micturating cystogram; urine cytology; renal biopsy.

Treatment

This most chronic disease (see

Table 11.7

) has profound effects on the patient and his or her relatives. The association between the patient and the renal physician and nursing staff becomes a very intense one, often lasting many years. It is important to ask detailed questions about the way the patient copes with the condition, whether work and travel are possible, and what the patient feels about the long-term prospects. Also ask whether a dialysis patient has considered accepting a kidney from a live donor.

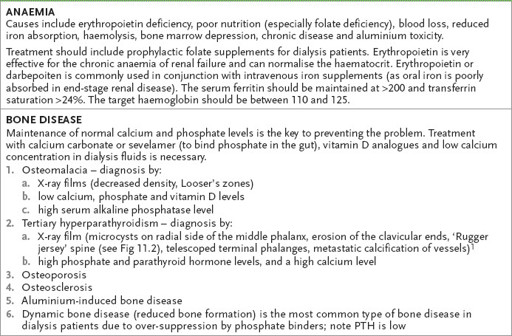

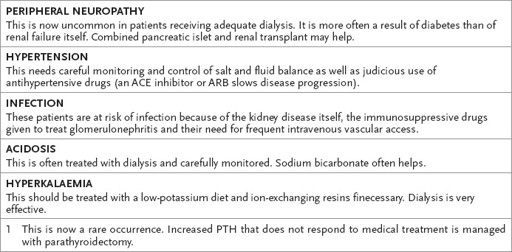

Table 11.7

Complications and treatment of chronic kidney disease

1.

Treat reversible causes of deterioration. These include:

a.

hypertension

b.

urinary tract infection

c.

urinary tract obstruction

d.

dehydration

e.

cardiac failure

f.

drug use (e.g. radiocontrast, NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, cyclosporin)

g.

hypercalcaemia

h.

hyperuricaemia with urate obstruction

i.

hypothyroidism or rarely hypoadrenalism.

2.

Monitor and control the blood pressure very carefully. Treat lipids.

3.

Carefully attend to salt and water balance and acidosis.

4.

Normalise the calcium and phosphate levels with diet, phosphate binders or calcitriol.

5.

Restrict dietary protein. Although this may delay slightly the need for dialysis, it leads to wasting and protein malnutrition. It is no longer universally recommended.

6.

Assess and treat sexual dysfunction.

7.

Dialyse when indicated (see below).

8.

Consider transplantation.

The absolute indications for dialysis are (see

Table 11.5

):

1.

uraemic symptoms despite conservative management (eGFR about 7 mL/min)