Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (11 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Fifth Avenue Parade

. The largest of all worldwide St. Patrick’s Day parades is the one up New York City’s Fifth Avenue. It began in 1762 as a proud display of Irish heritage, when the city was still confined to the lower tip of the island.

As the city spread uptown, the parade followed, higher and higher, until at one time it ran as far north as the area that is now Harlem. Over two hundred thousand people annually have taken part in this enormous showing of the green, a number that would have delighted the parade’s original organizers, Irish veterans of the Revolutionary War. For the group, composed

of both Catholics and Presbyterians, conceived the parade as a defiant public display against “nutty people who didn’t like the Irish very much.” They took to the streets to “show how many there were of them.”

Easter: 2nd Century, Rome

Easter, which in the Christian faith commemorates the Resurrection of Christ and consequently is the most sacred of all holy days, is also the name of an ancient Saxon festival and of the pagan goddess of spring and offspring, Eastre. How a once-tumultuous Saxon festival to Eastre was transformed into a solemn Christian service is another example of the supreme authority of the Church early in its history.

Second-century Christian missionaries, spreading out among the Teutonic tribes north of Rome, encountered numerous heathen religious observances. Whenever possible, the missionaries did not interfere too strongly with entrenched customs. Rather, quietly—and often ingeniously—they attempted to transform pagan practices into ceremonies that harmonized with Christian doctrine. There was a very practical reason for this. Converts publicly partaking in a Christian ceremony—and on a day when no one else was celebrating—were easy targets for persecution. But if a Christian rite was staged on the same day as a long-observed heathen one, and if the two modes of worship were not glaringly different, then the new converts might live to make other converts.

The Christian missionaries astutely observed that the centuries-old festival to Eastre, commemorated at the start of spring, coincided with the time of year of their own observance of the miracle of the Resurrection of Christ. Thus, the Resurrection was subsumed under the protective rubric Eastre (later spelled Easter), saving the lives of countless Christians.

For several decades, Easter was variously celebrated on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday. Finally, in

A.D

. 325, the Council of Nicaea, convened by the emperor Constantine, issued the so-called Easter Rule: Easter should be celebrated on “the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox.” Consequently, Easter is astronomically bound never to fall earlier than March 22 or later than April 25.

At this same council, Constantine decreed that the cross be adopted as the official symbol of the Christian religion.

Easter Bunny

. That a rabbit, or more accurately a hare, became a holiday symbol can be traced to the origin of the word “Easter.” According to the Venerable Bede, the English historian who lived from 672 to 735, the goddess Eastre was worshiped by the Anglo-Saxons through her earthly symbol, the hare.

The custom of the Easter hare came to America with the Germans who immigrated to Pennsylvania in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

From Pennsylvania, they gradually spread out to Virginia, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, New York, and Canada, taking their customs with them. Most eighteenth-century Americans, however, were of more austere religious denominations, such as Quaker, Presbyterian, and Puritan. They virtually ignored such a seemingly frivolous symbol as a white rabbit. More than a hundred years passed before this Teutonic Easter tradition began to gain acceptance in America. In fact, it was not until after the Civil War, with its legacy of death and destruction, that the nation as a whole began a widespread observance of Easter itself, led primarily by Presbyterians. They viewed the story of resurrection as a source of inspiration and renewed hope for the millions of bereaved Americans.

Easter Eggs

. Only within the last century were chocolate and candy eggs exchanged as Easter gifts. But the springtime exchanging of

real

eggs—white, colored, and gold-leafed—is an ancient custom, predating Easter by many centuries.

From earliest times, and in most cultures, the egg signified birth and resurrection.

The Egyptians buried eggs in their tombs. The Greeks placed eggs atop graves. The Romans coined a proverb:

Omne vivum ex ovo

,“All life comes from an egg.” And legend has it that Simon of Cyrene, who helped carry Christ’s cross to Calvary, was by trade an egg merchant. (Upon returning from the crucifixion to his produce farm, he allegedly discovered that all his hens’ eggs had miraculously turned a rainbow of colors; substantive evidence for this legend is weak.) Thus, when the Church started to celebrate the Resurrection, in the second century, it did not have to search far for a popular and easily recognizable symbol.

In those days, wealthy people would cover a gift egg with gilt or gold leaf, while peasants often dyed their eggs. The tinting was achieved by boiling the eggs with certain flowers, leaves, logwood chips, or the cochineal insect. Spinach leaves or anemone petals were considered best for green; the bristly gorse blossom for yellow; logwood for rich purple; and the body fluid of the cochineal produced scarlet.

In parts of Germany during the early 1880s, Easter eggs substituted for birth certificates. An egg was dyed a solid color, then a design, which included the recipient’s name and birth date, was etched into the shell with a needle or sharp tool. Such Easter eggs were honored in law courts as evidence of identity and age.

Easter’s most valuable eggs were hand crafted in the 1880s. Made by the great goldsmith Peter Carl Fabergé, they were commissioned by Czar Alexander III of Russia as gifts for his wife, Czarina Maria Feodorovna. The first Fabergé egg, presented in 1886, measured two and a half inches long and had a deceptively simple exterior. Inside the white enamel shell, though, was a golden yolk, which when opened revealed a gold hen with ruby eyes. The hen itself could be opened, by lifting the beak, to expose a

tiny diamond replica of the imperial crown. A still smaller ruby pendant hung from the crown. The Fabergé treasures today are collectively valued at over four million dollars. Forty-three of the fifty-three eggs known to have been made by Fabergé are now in museums and private collections.

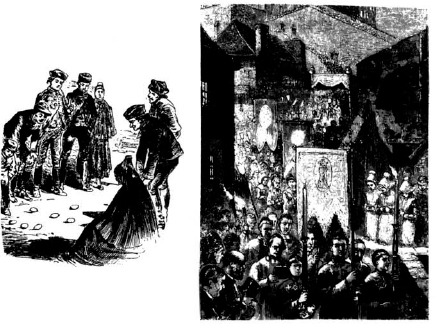

Easter egg rolling in Germany (left); Easter procession in Holland. Once a pagan feast honoring

Eastre,

goddess of spring and offspring, it later came to represent the Resurrection of Christ

.

Hot Cross Buns

. Traditionally eaten at Easter, the twice-scored biscuits were first baked by the Saxons in honor of Eastre. The word “bun” itself derives from

boun

, Saxon for “sacred ox,” for an ox was sacrificed at the Eastre festival, and the image of its horns was carved into the celebratory cakes.

The Easter treat was widespread in the early Western world. “Hot cross buns” were found preserved in the excavations at the ancient city of Herculaneum, destroyed in

A.D

. 79 along with Pompeii by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Early church fathers, to compete with the pagan custom of baking ox-marked cakes, used in numerous celebrations, baked their own version, employing the dough used for the consecrated host. Reinterpreting the ox-horn image as a crucifix, they distributed the somewhat-familiar-looking buns to new converts attending mass. In this way, they accomplished three

objectives: Christianized a pagan cake; gave the people a treat they were accustomed to; and subtly scored the buns with an image that, though decidedly Catholic, at a distance would not dangerously label the bearer “Christian.” The most desirable image on today’s hot cross buns is neither an ox horn nor a cross, but broad smears of glazed frosting.

April Fool’s Day: 1564, France

Many different explanations have been offered for the origins of April Fool’s Day, some as fanciful as April Fool jokes themselves.

One popular though unlikely explanation focuses on the fool that Christ’s foes intended to make of him, sending him on a meaningless round of visits to Roman officials when his fate had already been sealed. Medieval mystery plays frequently dramatized those events, tracing Christ’s journey from Annas to Caiaphas to Pilate to Herod, then back again to Pilate. (Interestingly, many cultures have a practice, predating Christianity, that involves sending people on “fool’s errands.”)

The most convincing historical evidence suggests that April Fooling originated in France under King Charles IX.

Throughout France in the early sixteenth century, New Year’s Day was observed on March 25, the advent of spring. The celebrations, which included exchanging gifts, ran for a week, terminating with dinners and parties on April 1.

In 1564, however, in beginning the adoption of the reformed, more accurate Gregorian calendar, King Charles proclaimed that New Year’s Day be moved back to January 1. Many Frenchmen who resisted the change, and others who merely forgot about it, continued partying and exchanging gifts during the week ending April 1. Jokers ridiculed these conservatives’ steadfast attachment to the old New Year’s date by sending foolish gifts and invitations to nonexistent parties. The butt of an April Fool’s joke was known as a

poisson d’Avril

, or “April fish” (because at that time of year the sun was leaving the zodiacal sign of Pisces, the fish). In fact, all events occurring on April 1 came under that rubric. Even Napoleon I, emperor of France, was nicknamed “April fish” when he married his second wife, Marie-Louise of Austria, on April 1, 1810.

Years later, when the country was comfortable with the new New Year’s date, Frenchmen, fondly attached to whimsical April Fooling, made the practice a tradition in its own right. It took almost two hundred years for the custom to reach England, from which it came to America.

Mother’s Day: 1908, Grafton, West Virginia

Though the idea of setting aside a day to honor mothers might seem to have ancient roots, our observance of Mother’s Day is not quite a century old. It originated from the efforts of a devoted daughter who believed that

grown children, preoccupied with their own families, too often neglect their mothers.

That daughter, Miss Anna Jarvis, a West Virginia schoolteacher, set out to rectify the neglect.

Born in 1864, Anna Jarvis attended school in Grafton, West Virginia. Her close ties with her mother made attending Mary Baldwin College, in Stanton, Virginia, difficult. But Anna was determined to acquire an education. Upon graduation, she returned to her hometown as a certified public school teacher.

The death of her father in 1902 compelled Anna and her mother to live with relatives in Philadelphia. Three years later, her mother died on May 9, leaving Anna grief-stricken. Though by every measure she had been an exemplary daughter, she found herself consumed with guilt for all the things she had not done for her mother. For two years these naggings germinated, bearing the fruit of an idea in 1907. On the second Sunday in May, the anniversary of her mother’s death, Anna Jarvis invited a group of friends to her Philadelphia home. Her announced idea—for an annual nationwide celebration to be called Mother’s Day—met with unanimous support. She tested the idea on others. Mothers felt that such an act of recognition was long overdue. Every child concurred. No father dissented. A friend, John Wanamaker, America’s number one clothing merchant, offered financial backing.

Early in the spring of 1908, Miss Jarvis wrote to the superintendent of Andrews Methodist Sunday School, in Grafton, where her mother had taught a weekly religion class for twenty years. She suggested that the local church would be the ideal location for a celebration in her mother’s honor. By extension, all mothers present would receive recognition.

So on May 10, 1908, the first Mother’s Day service was held in Grafton, West Virginia, attended by 407 children and their mothers. The minister’s text was, appropriately, John 19, verses 26 and 27, Christ’s parting words to his mother and a disciple, spoken from the cross: “Woman, behold thy son!” and “Behold thy Mother!”

At the conclusion of that service, Miss Jarvis presented each mother and child with a flower: a

carnation

, her own mother’s favorite. It launched a Mother’s Day tradition.

To suggest that the idea of an annual Mother’s Day celebration met with immediate public acceptance is perhaps an understatement. Few proposed holidays have had so much nationwide support, so little special-interest-group dissension. The House of Representatives quickly passed a Mother’s Day resolution. However, one Midwestern senator came off like Simon Legree. “Might as well have a Father’s Day,” the Congressional Record states. “Or a Mother-in-Law’s Day. Or an Uncle’s Day.” The resolution stalled in the Senate.