Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (9 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

The handshake once symbolized the transferral of authority from a god to a king. A fifteenth-century woodcut combines the musical tones “so” and “la” with Latin words to form

Sola fides sufficit,

suggesting good faith is conveyed through a handshake

.

Folklore offers an earlier, more speculative origin of the handshake: An ancient villager who chanced to meet a man he didn’t recognize reacted automatically by reaching for his dagger. The stranger did likewise, and the two spent time cautiously circling each other. If both became satisfied that the situation called for a parley instead of a fight to the death, daggers were reinserted into their sheaths, and right hands—the weapon hands—were extended as a token of goodwill. This is also offered as the reason why women, who throughout history were never the bearers of weapons, never developed the custom of the handshake.

Other customs of greeting have ancient origins:

The gentlemanly practice of tipping one’s hat goes back in principle to ancient Assyrian times, when captives were required to strip naked to demonstrate subjugation to their conquerors. The Greeks required new servants to strip from the waist up.

Removing an article of clothing became a standard act of respect. Romans approached a holy shrine only after taking their sandals off. And a person of low rank removed his shoes before entering a superior’s home—a custom the Japanese have brought, somewhat modified, into modern times. In England, women took off their gloves when presented to royalty. In fact,

two other gestures, one male, one female, are remnants of acts of subjugation or respect: the bow and the curtsy; the latter was at one time a full genuflection.

By the Middle Ages in Europe, the symbol of serfdom to a feudal lord was restricted to baring the head. The implicit message was the same as in earlier days: “I am your obedient servant.” So persuasive was the gesture that the Christian Church adopted it, requiring that men remove their hats on entering a church.

Eventually, it became standard etiquette for a man to show respect for an equal by merely tipping his hat.

On the Calendar

New Year’s Day: 2000

B.C

., Babylonia

Our word “holiday” comes from the Middle English

halidai

, meaning “holy day,” for until recently, humankind’s celebrations were of a religious nature.

New Year’s Day is the oldest and most universal of all such “holy day” festivals. Its story begins, oddly enough, at a time when there was as yet no such thing as a calendar year. The time between the sowing of seeds and the harvesting of crops represented a “year,” or cycle.

The earliest recorded New Year’s festival was staged in the city of Babylon, the capital of Babylonia, whose ruins stand near the modern town of al-Hillah, Iraq. The new year was celebrated late in March, at the vernal equinox, when spring begins, and the occasion lasted eleven days. Modern festivities pale by comparison. Initiating events, a high priest, rising two hours before dawn, washed in the sacred water of the Euphrates, then offered a hymn to the region’s chief god of agriculture, Marduk, praying for a bountiful new cycle of crops. The rump of a beheaded ram was rubbed against the temple walls to absorb any contagion that might infest the sacred edifice and, by implication, the next year’s harvest. The ceremony was called

kuppuru

—a word that appeared among the Hebrews at about the same time, in their Day of Atonement festival, Yom Kippur.

Food, wine, and hard liquor were copiously consumed—for the enjoyment they provided, but more important, as a gesture of appreciation to Marduk for the previous year’s harvest. A masked mummers’ play was enacted on the sixth day, a tribute to the goddess of fertility. It was followed

by a sumptuous parade—highlighted by music, dancing, and costumes—starting at the temple and terminating on the outskirts of Babylon at a special building known as the New Year House, whose archaeological remains have been excavated.

A high priest presiding over a New Year’s celebration, once a religious observance staged in spring to mark the start of a new agricultural season. Julius Caesar moved the holiday to the dead of winter

.

How New Year’s Day, essentially a seed-sowing occasion, shifted from the start of spring to the dead of winter is a strange, convoluted tale spanning two millennia.

From both an astronomical and an agricultural standpoint, January is a perverse time for symbolically beginning a crop cycle, or new year. The sun stands at no fiduciary place in the sky—as it does for the spring and autumn equinoxes and the winter and summer solstices, the four solar events that kick off the seasons. The holy day’s shift began with the Romans.

Under an ancient calendar, the Romans observed March 25, the beginning of spring, as the first day of the year. Emperors and high-ranking officials, though, repeatedly tampered with the length of months and years to extend their terms of office. Calendar dates were so desynchronized with astronomical benchmarks by the year 153

B.C

. that the Roman senate, to set many public occasions straight, declared the start of the new year as January 1. More tampering again set dates askew. To reset the calendar to January 1 in 46

B.C

., Julius Caesar had to let the year drag on for 445 days, earning it the historical sobriquet “Year of Confusion.” Caesar’s new calendar was

eponymously called the Julian calendar.

After the Roman conversion to Christianity in the fourth century, emperors continued staging New Year’s celebrations. The nascent Catholic Church, however, set on abolishing all pagan (that is, non-Christian) practices, condemned these observances as scandalous and forbade Christians to participate. As the Church gained converts and power, it strategically planned its own Christian festivals to compete with pagan ones—in effect, stealing their thunder. To rival the January 1 New Year’s holiday, the Church established its own January 1 holy day, the Feast of Christ’s Circumcision, which is still observed by Catholics, Lutherans, Episcopalians, and many Eastern Orthodox sects.

During the Middle Ages, the Church remained so strongly hostile to the old pagan New Year’s that in predominantly Catholic cities and countries the observance vanished altogether. When it periodically reemerged, it could fall practically anywhere. At one time during the high Middle Ages—from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries—the British celebrated New Year’s on March 25, the French on Easter Sunday, and the Italians on Christmas Day, then December 15; only on the Iberian peninsula was it observed on January 1.

It is only within the past four hundred years that January 1 has enjoyed widespread acceptance.

New Year’s Eve

. From ancient times, this has been the noisiest of nights.

For early European farmers, the spirits who destroyed crops with disease were banished on the eve of the new year with a great wailing of horns and beating of drums. In China, the forces of light, the Yang, annually routed the forces of darkness, the Yin, when on New Year’s Eve people gathered to crash cymbals and explode firecrackers. In America, it was the seventeenth-century Dutch, in their New Amsterdam settlement, who originated our modern New Year’s Eve celebration—though the American Indians may have set them a riotous example and paved the way.

Long before settlers arrived in the New World, New Year’s Eve festivities were observed by the Iroquois Indians, pegged to the ripening of the corn crop. Gathering up clothes, furnishings, and wooden household utensils, along with uneaten corn and other grains, the Indians tossed these possessions of the previous year into a great bonfire, signifying the start of a new year and a new life. It was one ancient act so literal in its meaning that later scholars did not have to speculate on its significance.

Anthropologist Sir James Frazer, in

The Golden Bough

, described other, somewhat less symbolic, New Year’s Eve activities of the Iroquois: “Men and women, variously disguised, went from wigwam to wigwam smashing and throwing down whatever they came across. It was a time of general license; the people were supposed to be out of their senses, and therefore not to be responsible for what they did.”

The American colonists witnessed the annual New Year’s Eve anarchy of

the Indians and were not much better behaved themselves, though the paucity of clothes, furnishings, and food kept them from lighting a Pilgrims’ bonfire. On New Year’s Eve 1773, festivities in New York City were so riotous that two months later, the legislature outlawed firecrackers, homemade bombs, and the firing of personal shotguns to commemorate all future starts of a new year.

Mummers’ Parade

. Bedecked in feathered plumes and strutting to the tune “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” the Mummers make their way through the streets of Philadelphia, led by “King Momus,” traditional leader of the parade. This method of welcoming in the New Year is of English, Swedish, and German derivation.

Modern mumming is the European practice of going from house to house dressed in costumes and presenting plays for money or treats. As the practice developed in eighteenth-century England and Ireland, a masked man, designated the “champion” (in ancient mumming rites, the “god”), is slain in a mock fight, then resurrected by a masked “doctor” (originally, “high priest”). The ancient mumming ceremony, staged in spring, symbolized the rebirth of crops, and its name comes from the Greek

mommo

, meaning “mask.”

The Swedes adopted British mumming. And they enriched it with the German New Year’s tradition of a street festival, marching bands, and the pagan practice of parading in animal skins and feathers. The Swedes who settled along the Delaware River established the practice in America, which in Philadelphia turned into the spectacular Mummers’ Day Parade.

Tournament of Roses

. This famous Pasadena, California, parade was started on January 1, 1886, by the local Valley Hunt Club. Members decorated their carriages with flowers, creating what the club’s charter described as “an artistic celebration of the ripening of the oranges in California.” (The intent is not dissimilar to that of the ancient Babylonians, who marked the new year with a parade and the sowing of seeds.) In the afternoon, athletic events were staged.

The Rose Bowl football game became part of the festivities in 1902, but the following year, chariot races (a Roman New Year’s event) provided the main sports thrills. It wasn’t until 1916 that the football game returned, to become the annual attraction. Since then, New Year’s parades, parties, pageants, and bowl games have proliferated and occupy a large share of today’s celebrations—the very kinds of secular events that for centuries equated celebrating New Year’s with sinning.

New Year’s Resolutions

. Four thousand years ago, the ancient Babylonians made resolutions part of their New Year’s celebrations. While two of the most popular present-day promises might be to lose weight and to quit

smoking, the Babylonians had their own two favorites: to pay off outstanding debts and to return all borrowed farming tools and household utensils.

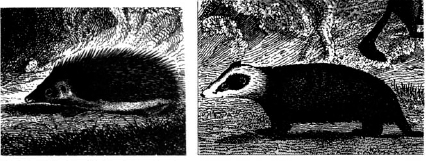

The lore of a groundhog (left) predicting the start of spring began in Germany where the forecasting animal was actually a badger (right

).

New Year’s Baby

. The idea of using an infant to symbolize the start of a new cycle began in ancient Greece, about 600

B.C

. It was customary at the festival of Dionysus, god of wine and general revelry, to parade a babe cradled in a winnowing basket. This represented the annual rebirth of that god as the spirit of fertility. In Egypt, a similar rebirth ceremony was portrayed on the lid of a sarcophagus now in a British museum: Two men, one old and bearded, the other in the fitness of youth, are shown carrying an infant in a winnowing basket.

So common was the symbol of the New Year’s babe in Greek, Egyptian, and Roman times that the early Catholic Church, after much resistance, finally allowed its members to use it in celebrations—if celebrators acknowledged that the infant was not a pagan symbol but an effigy of the Christ Child.