Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (36 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

“Hey Diddle Diddle”: Post-1569, Europe

Hey diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle

,

The cow jumped over the moon

…

Any rhyme in which a cow jumps over the moon and a dish runs away with a spoon is understandably classified in the category “nonsense rhymes.” The verse, meant to convey no meaning but only to rhyme, was composed entirely around a European dance, new in the mid-1500s, called “Hey-didle-didle.” The object was to have something metrical to sing while dancing.

“Humpty Dumpty”: 15th Century, England

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses,

And all the king’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again

.

Scholars of linguistics believe this rhyme may be five hundred years old and may have mocked a nobleman who fell from high favor with a king, the fifteenth-century British monarch Richard III. From England the rhyme spread to several European countries, where its leading character changed from “Humpty Dumpty” to “Thille Lille” (in Sweden), “Boule, Boule” (in France), and “Wirgele-Wargele” (in Germany).

In the 1600s, “humpty dumpty” became the name of a hot toddy of ale and brandy, and one hundred fifty years later, it entered British vernacular as “a short clumsy person of either sex.”

“Jack and Jill”: Pre-1765, England

Jack and Jill went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water;

Jack fell down and broke his crown

,

And Jill came tumbling after

.

A 1765 British woodcut illustrating this rhyme shows two boys, named Jack and Gill; there is no mention or depiction of a girl named Jill. Some folklorists believe the boys represent the influential sixteenth-century cardinal Thomas Wolsey and his close colleague, Bishop Tarbes.

In 1518, when Wolsey was in the service of Henry VII, Western Europe was split into two rival camps, France and the Holy Roman Empire of the Hapsburgs. Wolsey and Tarbes traveled back and forth between the enemies, attempting to negotiate a peace. When they failed, full-scale war erupted. Wolsey committed British troops against France, and to finance the campaign he raised taxes, arousing widespread resentment. The rhyme is thought to parody his “uphill” peace efforts and their eventual failure.

“Jack Be Nimble”: Post-17th Century, England

Jack be nimble,

Jack be quick,

Jack jumped over

The candle stick

.

The verse is based on both an old British game and a once-popular means of auguring the future: leaping over a lit candle.

In the game and the augury, practiced as early as the seventeenth century, a lighted candle was placed in the center of a room. A person who jumped over the flame without extinguishing it was supposed to be assured good fortune for the following year. The custom became part of traditional British festivities that took place on November 25, the feast day of St. Catherine, the fourth-century Christian martyr of Alexandria.

“This Is the House That Jack Built”: Post-1500s, Europe

This is the house that Jack built

.

This is the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built

.

This is the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built

….

This is an example of an “accumulative rhyme,” in which each stanza repeats all the previous ones, then makes its own contribution.

The origin of “The House That Jack Built” is thought to be a Hebrew accumulative chant called “Had Gadyo,” which existed in oral tradition and was printed in the sixteenth century, although the subject matter in the two verses is unrelated. The point of an accumulative rhyme was not to convey information or to parody or satirize a subject, but only to tax a child’s powers of recall.

“Little Jack Horner”: Post-1550, England

Little Jack Horner

Sat in the corner,

Eating a Christmas pie

…

At the end of this rhyme, when Jack pulls a plum from the pie and

exclaims “What a good boy am I!” he is actually commenting on his deviousness, for the tasty plum is a symbol for something costly that the real “Jack” stole.

Jack Homer extracting the deed for Mells Manor

.

Legend has it that the original Jack Horner was Thomas Horner, sixteenth-century steward to Richard Whiting, abbot of Glastonbury in Somerset, the richest abbey in the British kingdom under King Henry VIII.

Abbot Richard Whiting suspected that Glastonbury was about to be confiscated by the crown during this period in history, known as the Dissolution of Monasteries. Hoping to gain favor with the king, Whiting sent Thomas Horner to London with a gift of a Christmas pie.

It was no ordinary pie. Beneath the crust lay the title deeds to twelve manor houses—a token that the abbot hoped would placate King Henry. En route to London, Horner reached into the pie and extracted one plum of a deed—for the expansive Mells Manor—and kept it for himself.

Soon after King Henry dissolved the abbot’s house, Thomas Horner took up residence at Mells Manor, and his descendants live there to this day—though they maintain that their illustrious ancestor legally purchased the deed to the manor from Abbot Whiting.

Interestingly, Richard Whiting was later arrested and tried on a trumped-up charge of embezzlement. Seated in the corner of the jury was his former steward, Thomas Horner. The abbot was found guilty and hanged, then drawn and quartered. Horner not only was allowed to retain Mells Manor but was immortalized in one of the world’s best-known, best-loved nursery rhymes.

“Ladybird, Ladybird”: Pre-18th Century, Europe

Ladybird, ladybird

,

Fly away home

,

Your house is on fire

And your children all gone

.

Today the rhyme accompanies a game in which a child places a ladybug on her finger and recites the verse. If the insect does not voluntarily fly away, it is shaken off. According to an eighteenth-century woodcut, that is precisely what children did in the reign of George II.

The rhyme, though, is believed to have originated as an ancient superstitious incantation. Composed of slightly different words, it was recited to guide the sun through dusk into darkness, once regarded as a particularly mysterious time because the heavenly body vanished for many hours.

“London Bridge”: Post-11th Century, England

London Bridge is broken down,

Broken down, broken down,

London Bridge is broken down,

My fair lady

.

The first stanza of this rhyme refers to the actual destruction, by King Olaf of Norway and his Norsemen in the eleventh century, of an early timber version of the famous bridge spanning the Thames. But there is more to the story than that.

Throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, there existed a game known as Fallen Bridge. Its rules of play were virtually identical in every country. Two players joined hands so that their elevated arms formed a bridge. Other players passed beneath, hoping that the arms did not suddenly descend and trap them.

In Italy, France, Germany, and England, there are rhymes based on the game, and “London Bridge” is one example. But the remainder of the long, twelve-stanza poem, in which all attempts to rebuild London Bridge fail, reflects an ancient superstition that man-made bridges, which unnaturally span rivers, incense water gods.

Among the earliest written records of this superstition are examples of living people encased in the foundations of bridges as sacrifices. Children were the favored sacrificial victims. Their skeletons have been unearthed in the foundations of ancient bridges from Greece to Germany. And British

folklore makes it clear that to ensure good luck, the cornerstones of the first nontimber London Bridge, built by Peter of Colechurch between 1176 and 1209, were splattered with the blood of little children.

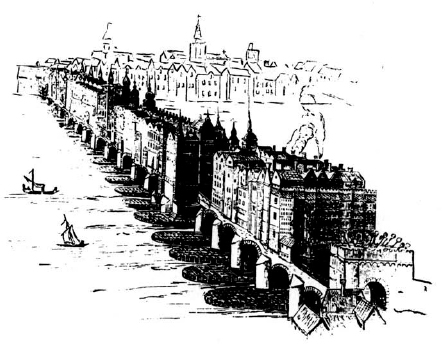

London Bridge, c. 1616. To appease water gods children were buried in bridge foundations

.

“See-Saw, Margery Daw”: 17th Century, British Isles

See-saw, Margery Daw,

Jacky shall have a new master;

Jacky shall have but a penny a day,

Because he can’t work any faster

.

This was originally sung in the seventeenth century by builders, to maintain their to-and-fro rhythm on a two-handed saw. But there is a ribald meaning to the words. “Margery Daw” was then slang for a slut, suggesting that the rugged, hard-working builders found more in the rhyme to appreciate than meter.

A more explicit version of the verse, popular in Cornwall, read: “See-saw, Margery Daw / Sold her bed and lay upon straw,” concluding with: “For wasn’t she a dirty slut / To sell her bed and lie in the dirt?”

Later, the rhyme was adopted by children springing up and down on a see-saw.

“Mary Had a Little Lamb”: 1830, Boston

Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow;

And everywhere that Mary went

The lamb was sure to go

.

These are regarded as the best-known four lines of verse in the English language. And the words “Mary had a little lamb,” spoken by Thomas Edison on November 20, 1877, into his latest invention, the phonograph, were the first words of recorded human speech.

Fortunately, there is no ambiguity surrounding the authorship of this tale, in which a girl is followed to school by a lamb that makes “the children laugh and play.” The words capture an actual incident, recorded in verse in 1830 by Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale of Boston, editor of the widely read

Ladies’ Magazine

.

Mrs. Hale (who launched a one-woman crusade to nationalize Thanksgiving Day; see page 64) was also editor of

Juvenile Miscellany

. When she was told of a case in which a pet lamb followed its young owner into a country schoolhouse, she composed the rhyme and published it in the September-October 1830 issue of the children’s journal. Its success was immediate—and enduring.

“Mary, Mary”: 18th Century, England

Mary, Mary, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?

With silver bells and cockle shells,

And pretty maids all in a row

.

The rhyme originated in the eighteenth century and there are two schools of thought concerning its meaning, one secular, the other ecclesiastic.

The “silver bells,” argue several Catholic writers, are “sanctus bells” of mass; the “cockle shells” represent badges worn by pilgrims; and the “pretty maids all in a row” are ranks of nuns marching to church services. Mary is of course the Blessed Virgin. This argument is as old as the rhyme.