Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (59 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

If you purse your lips, you are contracting them into wrinkles and folds, similar in appearance to the mouth of a drawstring bag, ancient people’s earliest purse. But it was the material from which those early bags were made, hide, or

byrsa

in Greek, that is the origin of the word “purse.”

The Romans adopted the Greek drawstring

byrsa

unaltered, Latinizing its name to

bursa

. The early French made it

bourse

, which also came to mean the money in the purse, and then became the name of the stock exchange in Paris, the Bourse.

Until pockets appeared in clothing in the sixteenth century, men, women, and children carried purses—sometimes no more than a piece of cloth that held keys and other personal effects, or at the other extreme, elaborately embroidered and jeweled bags.

Handkerchief: Post-15th Century, France

During the fifteenth century, French sailors returned from the Orient with large, lightweight linen cloths that they had seen Chinese field-workers use as protective head covers in the sun. Fashion-minded French women, impressed with the quality of the linen, adopted the article and the practice, naming the headdress a

couvrechef

, meaning “covering for the head.” The British took up the custom and Anglicized the word to “kerchief.” Since these coverings were carried in the hand until needed in sunlight, they were referred to as “hand kerchiefs.”

Since upper-class European women, unlike Chinese in the rice paddies, already carried sun-shielding parasols, the hand kerchief was from the start a fashion affectation. This is evident in numerous illustrations and paintings of the period, in which elaborately decorated hand kerchiefs are seldom worn but prominently carried, waved, and demurely dropped. Hand kerchiefs of silk, some with silver or gold thread, became so costly in the 1500s that they often were mentioned in wills as valuables.

It was during the reign of Elizabeth I that the first lace hand kerchiefs appeared in England. Monogrammed with the name of a loved one, the articles measured four inches square, and had a tassel dangling from one corner. For a time, they were called “true love knots.” A gentleman wore one bearing his lady’s initials tucked into his hatband; and she carried his love knot between her breasts.

When, then, did the Chinese head cover, which became the European hand kerchief, become a handkerchief, held to the nose? Perhaps not long after the hand kerchief was introduced into European society. However, the nose-blowing procedure was quite different then than today.

Throughout the Middle Ages, people cleared their noses by forcefully exhaling into the air, then wiped their noses on whatever was handy, most

often a sleeve. Early etiquette books explicitly legitimize the practice. The ancient Romans had carried a cloth called a

sudarium

, meaning “sweat cloth,” which was used both to wipe the brow on hot days and to blow the nose. But the civility of the

sudarium

fell with the Roman Empire.

The first recorded admonitions against wiping the nose on the sleeve (though not against blowing the nose into the air) appear in sixteenth-century etiquette books—during the ascendancy of the hand kerchief. In 1530, Erasmus of Rotterdam, a chronicler of customs, advised: “To wipe your nose with your sleeve is boorish. The hand kerchief is correct, I assure you.”

From that century onward, hand kerchiefs made contact, albeit tentatively at first, with the nose. The nineteenth-century discovery of airborne germs did much to popularize the custom, as did the machine age mass production of inexpensive cotton cloths. The delicate hand kerchief became the dependable handkerchief.

Fan: 3000

B.C

., China and Egypt

Peacock-feather fans, and fans of papyrus and palm fronds: these decorative and utilitarian breeze-stirrers developed simultaneously and independently about five thousand years ago in two disparate cultures. The Chinese turned fans into an art; the Egyptians, into a symbol of class distinction.

Numerous Egyptian texts and paintings attest to the existence of a wealthy man’s “fan servant” and a pharaoh’s “royal fan bearer.” Slaves, both white-skinned and black-skinned, continually swayed huge fans of fronds or woven papyrus to cool masters. And the shade cast on the ground by opaque fans was turf forbidden to commoners. In semitropical Egypt, the intangibles of shade and breeze were desiderata that, owing to the vigilance of slaves, adorned the wealthy as prestigiously as attire.

In China, fans cooled more democratically. And the fans themselves were considerably more varied in design and embellishment. In addition to the iridescent peacock-feather fan, the Chinese developed the “screen” fan: silk fabric stretched over a bamboo frame and mounted on a lacquered handle. In the sixth century

A.D

., they introduced the screen fan to the Japanese, who, in turn, conceived an ingenious modification: the folding fan.

The Japanese folding fan consisted of a solid silk cloth attached to a series of sticks that could collapse in on each other. Folding fans, depending on their fabric, color, and design, had different names and prescribed uses. Women, for instance, had “dance” fans, “court” fans, and “tea” fans, while men carried “riding” fans and even “battle” fans.

The Japanese introduced the folding fan to China in the tenth century. At that point, it was the Chinese who made a clever modification of the Japanese design. Dispensing with the solid silk cloth stretched over separate sticks, the Chinese substituted a series of “blades” in bamboo or ivory.

These thin blades alone, threaded together at their tops by a ribbon, constituted the fan, which was also collapsible. Starting in the fifteenth century, European merchants trading in the Orient returned with a wide variety of decorative Chinese and Japanese fans. By far the most popular model was the blade fan, or

brise

, with blades of intricately carved ivory strung together with a ribbon of white or red silk.

Safety Pin: 1000

B.C

., Central Europe

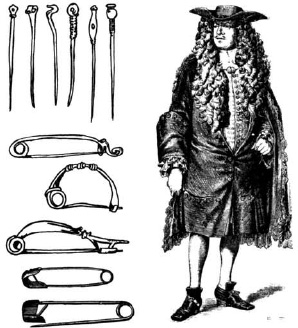

In the modern safety pin, the pinpoint is completely and harmlessly concealed in a metal sheath. Its ancestor had its point cradled away, though somewhat exposed, in a curved wire. This bent, U-shaped device originated in Central Europe about three thousand years ago and marked the first significant improvement in design over the straight pin. Several such pins in bronze have been unearthed.

Straight pins, of iron and bone, had been fashioned by the Sumerians around 3000

B.C

. Sumerian writings also reveal the use of eye needles for sewing. Archaeologists, examining ancient cave drawings and artifacts, conclude that even earlier peoples, some ten thousand years ago, used needles, of fish spines pierced in the top or middle to receive the thread.

By the sixth century

B.C

, Greek and Roman women fastened their robes on the shoulder and upper arm with a

fibula

. This was an innovative pin in which the middle was coiled, producing tension and providing the fastener with a spring-like opening action. The

fibula

was a step closer to the modern safety pin.

In Greece, straight stick pins were used as ornamental jewelry. “Stilettos,” in ivory and bronze, measuring six to eight inches, adorned hair and clothes. Aside from belts, pins remained the predominant way to fasten garments. And the more complex wraparound and slip-on clothing became, the more numerous were the fastening pins required. A palace inventory of 1347 records the delivery of twelve thousand pins for the wardrobe of a French princess.

Not surprisingly, the handmade pins were often in short supply. The scarcity could drive up prices, and there are instances in history of serfs taxed to provide feudal lords with money for pins. In the late Middle Ages, to remedy a pin shortage and stem the overindulgence in and hoarding of pins, the British government passed a law allowing pinmakers to market their wares only on certain days of the year. On the specified days, upper-and lower-class women, many of whom had assiduously saved “pin money,” flocked to shops to purchase the relatively expensive items. Once the price of pins plummeted as a result of mass machine production, the phrase “pin money” was equally devalued, coming to mean “a wife’s pocket money,” a pittance sufficient to purchase only pins.

The esteemed role of pins in the history of garments was seriously undermined by the ascendancy of the functional button.

Garment pins from the Bronze Age (top); three Roman safety pins, c. 500 B.C. (middle); modern version. Pinned garments gave way to clothes that buttoned from neck to hem

.

Button: 2000

B.C

., Southern Asia

Buttons did not originate as clothes fasteners. They were decorative, jewelry-like disks sewn on men’s and women’s clothing. And for almost 3,500 years, buttons remained purely ornamental; pins and belts were viewed as sufficient to secure garments.

The earliest decorative buttons date from about 2000

B.C

. and were unearthed at archaeological digs in the Indus Valley. They are seashells, of various mollusks, carved into circular and triangular shapes, and pierced with two holes for sewing them to a garment.

The early Greeks and Romans used shell buttons to decorate tunics, togas, and mantles, and they even attached wooden buttons to pins that fastened to clothing as a broach. Elaborately carved ivory and bone buttons, many leafed with gold and studded with jewels, were retrieved from European ruins. But nowhere, in illustration, text, or garment fragment, is there the slightest indication that an ancient tailor conceived the idea of opposing a button with a buttonhole.

When did the noun “button” become a verb? Surprisingly, not until the thirteenth century.

Buttonhole

. The practice of buttoning a garment originated in Western Europe, and for two reasons.

In the 1200s, baggy, free-flowing attire was beginning to be replaced

with tighter, form-fitting clothing. A belt alone could not achieve the look, and while pins could (and often did), they were required in quantity; and pins were easily misplaced or lost. With sewn-on buttons, there was no daily concern over finding fasteners when dressing.

The second reason for the introduction of buttons with buttonholes involved fabric. Also in the 1200s, finer, more delicate materials were being used for garments, and the repeated piercing of fabrics with straight pins and safety pins damaged the cloth.

Thus, the modern, functional button finally arrived. But it seemed to make up for lost time with excesses. Buttons and buttonholes appeared on every garment. Clothes were slit from neck to ankle simply so that a parade of buttons could be used to close them. Slits were made in impractical places—along sleeves and down legs—just so the wearer could display buttons that actually buttoned. And buttons were contiguous, as many as two hundred closing a woman’s dress—enough to discourage undressing. If searching for misplaced safety pins was time-consuming, buttoning garments could not have been viewed as a time-saver.

Statues, illustrations, and paintings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries attest to button mania. The mode peaked in the next century, when buttons, in gold and silver and studded with jewels, were sewn on clothing merely as decorative features—as before the creation of the buttonhole.

In 1520, French king Francis I, builder of Fontainebleau castle, ordered from his jeweler 13,400 gold buttons, which were fastened to a single black velvet suit. The occasion was a meeting with England’s Henry VII, held with great pomp and pageantry on the Field of Cloth of Gold near Calais, where Francis vainly sought an alliance with Henry.

Henry himself was proud of his jeweled buttons, which were patterned after his rings. The buttoned outfit and matching rings were captured on canvas by the German portrait painter Hans Holbein.

The button craze was somewhat paralleled in this century, in the 1980s, though with zippers. Temporarily popular were pants and shirts with zipped pockets, zipped openings up the arms and legs, zipped flaps to flesh, and myriad other zippers to nowhere.

Right and Left Buttoning

. Men button clothes from right to left, women from left to right. Studying portraits and drawings of buttoned garments, fashion historians have traced the practice back to the fifteenth century. And they believe they understand its origin.

Men, at court, on travels, and on the battlefield, generally dressed themselves. And since most humans are right-handed, the majority of men found it expeditious to have garments button from right to left.

Women who could afford the expensive buttons of the day had female dressing servants. Maids, also being predominantly right-handed, and facing buttons head-on, found it easier to fasten their mistresses’ garments if the buttons and buttonholes were sewn on in a mirror-image reversal. Tailors complied, and the convention has never been altered or challenged.