Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (62 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

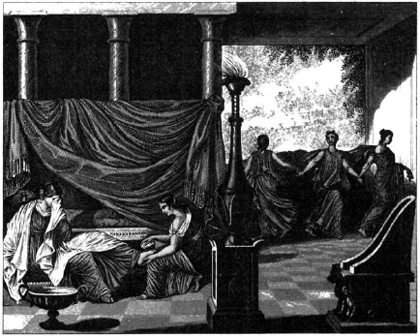

The Egyptians were better bedded—though their pillows were no softer. Palaces in the fourth millennium

B.C

. allowed for a “master bedroom,” usually fitted with a draped, four-poster bed, and surrounding narrow “apartments” for a wife and children, each with smaller beds.

The best Egyptian bedrooms had double-thick walls and a raised platform for the bed, to insulate the sleeper from midnight cold, midday heat, and

low drafts. Throughout most of the ancient world, beds were for sleeping at night, reclining by day, and stretching out while eating.

Most Egyptian beds had canopies and draped curtains to protect from a nightly nuisance: mosquitoes. Along the Nile, the insects proved such a persistent annoyance that even commoners slept beneath (or wrapped cocoon-like in)

mosquito netting

. Herodotus, regarded as the “father of history,” traveled throughout the ancient world recording the peoples and behaviors he encountered. He paints a picture of a mosquito-infested Egypt that can elicit sympathy from any person today who struggles for a good night’s sleep in summer:

In parts of Egypt above the marshes the inhabitants pass the night upon lofty towers, as the mosquitoes are unable to fly to any height on account of the winds. In the marshy country, where there are no towers, each man possesses a net. By day it serves him to catch fish, while at night he spreads it over the bed, and creeping in, goes to sleep underneath. The mosquitoes, which, if he rolls himself up in his dress or in a piece of muslin, are sure to bite through the covering, do not so much as attempt to pass the net.

Etymologists find a strong association between the words “mosquito” and “canopy.” Today “canopy” suggests a splendid drape, but to the ancient Greeks,

konops

referred to the mosquito. The Romans adopted the Greeks’ mosquito netting and Latinized

konops

to

conopeum

, which the early inhabitants of Britain changed to

canape

. In time, the name came to stand for not the mosquito itself but the bed draping that protected from the insect.

Whereas the Egyptians had large bedrooms and beds, the Greeks, around 600

B.C

., led a more austere home life, which was reflected in the simplicity of their bedrooms. The typical sleeping chamber of a wealthy Greek man housed a plain bed of wood or wicker, a coffer for valuables, and a simple chair. Many Spartan homes had no actual bedroom because husbands, through military duty, were separated from wives for a decade or longer. A Spartan youth at age twenty joined a military camp, where he was required to sleep. If married, he could visit his wife briefly after supper, but he could not sleep at home until age thirty, when he was considered a full citizen of Greece.

Roman bedrooms were only slightly less austere than those of the Greeks. Called

cubicula

(giving us the word “cubicle”), the bedroom was more a closet than a room, closed by a curtain or door. These cubicles surrounded a home’s or palace’s central court and contained a chair, chamber pot, and simple wooden bed, often of oak, maple, or cedar. Mattresses were stuffed with either straw, reeds, wool, feathers, or swansdown, depending on a person’s finances. Mosquito netting was commonplace.

Though some Roman beds were ornately carved and outfitted with expensive linens and silk, most were sparsely utilitarian, reflecting a Roman work ethic. On arising, men and women did not bathe (that took place midday at public facilities; see page 200), nor did breakfast consist of anything more than a glass of water. And dressing involved merely draping a toga over undergarments that served as nightclothes. For Romans prided themselves on being ready to commence a day’s work immediately upon arising. The emperor Vespasian, for instance, who oversaw the conquest of Britain and the construction of the Colosseum, boasted that he could prepare himself for imperial duties, unaided by servants, within thirty seconds of waking.

Canopy derives from the Greek word for mosquito, and canopied beds protected ancient peoples from the nightly nuisance

.

Making a Bed

. The decline of the bed and the bedroom after the fall of the Roman Empire is aptly captured in the phrase “make the bed.” This simple expression, which today means no more than smoothing out sheets and blankets and fluffing a pillow or two, was a literal statement throughout the Dark Ages.

From about

A.D

. 500 onward, it was thought no hardship to lie on the floor at night, or on a hard bench above low drafts, damp earth, and rats. To be indoors was luxury enough. Nor was it distasteful to sleep huddled closely together in company, for warmth was valued above privacy. And, too, in those lawless times, safety was to be found in numbers.

Straw stuffed into a coarse cloth sack could be spread on a table or bench by a guest in a home or an inn, to “make a bed.” And since straw was routinely removed to dry out, or to serve a daytime function, beds were made and remade.

The downward slide of beds and bedroom comfort is reflected in another term from the Middle Ages: bedstead. Today the word describes a bed’s framework for supporting a mattress. But to the austere-living Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, a bedstead was merely the location on the floor where a person bedded down for the night.

Hardship can be subtly incorporated into custom. And throughout the British Isles, the absence of comfortable beds was eventually viewed as a plus, a nightly means of strengthening character and body through travail. Soft beds were thought to make soft soldiers. That belief was expressed by Edgar, king of the Scots, at the start of the 1100s. He forbade noblemen, who could afford comfortable down mattresses, to sleep on any soft surface that would pamper them to effeminacy and weakness of character. Even undressing for bed (except for the removal of a suit of mail armor) was viewed as a coddling affectation. So harshly austere was Anglo-Saxon life that the conquering Normans regarded their captives as only slightly more civilized than animals.

Spring Mattress: Late 18th Century, England

Mattresses once were more nightmarish, in the bugs and molds they harbored, than a sleeper’s worst dreams. Straw, leaves, pine needles, and reeds—all organic stuffings—mildewed and rotted and nurtured bedbugs. Numerous medieval accounts tell of mice and rats, with the prey they captured, nesting in mattresses not regularly dried out and restuffed. Leonardo da Vinci, in the fifteenth century, complained of having to spend the night “upon the spoils of dead creatures” in a friend’s home. Physicians recommended adding such animal repellents as garlic to mattress stuffing.

Until the use of springs and inorganic stuffings, the quest for a comfortable, critter-free mattress was unending. Indeed, as we’ve seen, one reason to “make a bed” anew each day was to air and dry out the mattress stuffing.

Between da Vinci’s time and the birth of the spring mattress in the eighteenth century, numerous attempts were made to get a comfortable, itch-free night’s repose. Most notable perhaps was the 1500s French

air mattress

. Known as a “wind bed,” the mattress was constructed of heavily waxed canvas and equipped with air valves for inflation by mouth or mechanical pump. The brainchild of upholsterer William Dujardin, history’s first air mattress enjoyed a brief popularity among the French nobility of the period, but cracking from repeated or robust use severely shortened its lifetime. A number of air beds made from more flexible oilcloth were available in London in the seventeenth century, and in Ben Jonson’s 1610

play

The Alchemist

, a character states his preference for air over straw, declaring, “I will have all my beds blown up, not stuffed.”

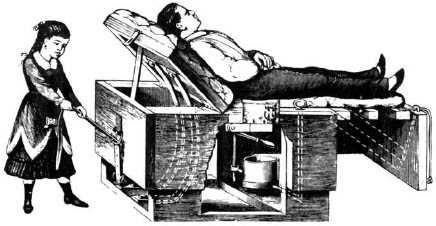

Adjustable sick bed, incorporating a chamber pot

.

British patents for springs—in furniture and carriage seats—began to appear in the early eighteenth century. They were decidedly uncomfortable at first. Being perfectly cylindrical (as opposed to conical), springs when sat upon snaked to one side rather than compressing vertically; or they turned completely on their sides. And given the poor metallurgical standards of the day, springs might snap, poking hazardously through a cushion.

Spring mattresses were attempted. But they presented complex technological problems since a reclining body offers different compressions along its length. Springs sturdy enough to support the hips, for instance, were unyielding to the head, while a spring made sensitive for the head was crushed under the weight of the hips.

By the mid-1850s, the conical innerspring began to appear in furniture seats. The larger circumference of its base ensured a more stable vertical compression. An early mention of sleeping on conical innersprings appeared in an 1870s London newspaper: “Strange as it may seem, springs can be used as an excellent sleeping arrangement with only a folded blanket above the wires.” The newspaper account emphasized spring comfort: “The surface is as sensitive as water, yielding to every pressure and resuming its shape as soon as the body is removed.”

Early innerspring mattresses were handcrafted and expensive. One of the first patented in America, by an inventor from Poughkeepsie, New York, was too costly to arouse interest from any United States bedding manufacturer. For many years, innerspring-mattress beds were found chiefly in luxury hotels and in ocean liners such as the

Mauretania, Lusitania

, and

Titanic

. As late as 1925, when U.S. manufacturer Zalmon Simmons conceived of his “Beautyrest” innerspring mattress, its $39.50 price tag was

more than twice what Americans paid for the best hair-stuffed mattress of the day.

Simmons, however, cleverly decided not to sell just a mattress but to sell

sleep

— “scientific sleep,” at that. Beautyrest advertisements featured such creative geniuses of the era as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, H. G. Wells, and Guglielmo Marconi. The company promoted “scientific sleep” by informing the public of the latest findings in the relatively new field of sleep research: “People do not sleep like logs; they move and turn from twenty-two to forty-five times a night to rest one set of muscles and then another.”

With several of the most creative minds of the day stressing how they benefited from a good night’s sleep, it is not surprising that by 1929, Beautyrest, the country’s first popular innerspring mattress, had annual sales of nine million dollars. Stuffed mattresses were being discarded faster than trashmen could collect them.

Electric Blanket: 1930s, United States

Man’s earliest blankets were animal skins, or “choice fleeces,” as they are referred to in the

Odyssey

. But our word “blanket” derives from a later date and a different kind of bed covering. French bed linens (and bedclothes) during the Middle Ages consisted largely of undyed woolen cloth, white in color and called

blanquette

, from

blanc

, meaning “white.” In time, the word evolved to “blanket” and it was used solely for the uppermost bed covering.

The first substantive advance in blankets from choice fleeces occurred in this century and as a spinoff from a medical application of electricity. In 1912, while large areas of the country were still being wired for electric power, American inventor S. I. Russell patented an electric heating pad to warm the chests of tubercular sanitarium patients reclining outdoors. It was a relatively small square of fabric with insulated heating coils wired throughout, and it cost a staggering $150.

Almost immediately, the possibility for larger, bed-sized electric blankets was appreciated; and not only for the ailing. But cost, technology, and safety were obstacles until the mid-1930s. The safety of electric blankets remained an issue for many years. In fact, most refinements to date involved generating consistent heat without risking fire. One early advance involved surrounding heating elements with nonflammable plastics, a spin-off of World War II research into perfecting electrically heated flying suits for pilots.

Birth Control: 6 Million Years Ago, Africa and Asia