Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (60 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

Was

Death and Life

worthy of being the one measure of all things urban? Was Jane right in all she preached,

correct in all she saw? Obviously not. On the other hand, the book’s influence didn’t hang on the validity of any one specific claim. It was more than a collection of insights and assertions; it was a manifesto, one that looked at the city from a fresh, deeply sympathetic point of view. Jane took Le Corbusier, Ebenezer Howard, and many others and corralled them into a single pen; all were, by her lights, anti-city. Whereas she alone,

Death and Life

could seem to say, was the city’s last, best champion. And though you could chip away at this or that of her claims, it didn’t

matter

in the end; because the book’s sweeping, irreducible essence remained and you could never see cities the same way again.

In 1962, a year after

Death and Life

first appeared, Thomas S. Kuhn introduced the concept of a paradigm shift. Kuhn was a historian of science who thought about how scientific ideas are shaped and changed—how, for example, the Copernican revolution reshaped the heavens from that of the old Ptolemaic view. His book,

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

, had nothing to say about cities, or about the social sciences generally. But its ideas were so seductive that scholars in numerous other disciplines—in economics, political science, and sociology as well as the hard sciences—began to apply them to their own fields.

Science doesn’t happen by the slow accumulation of neutral facts gradually worked into theories, Kuhn said. Rather, at any moment in a science’s evolution, some particular theory is the prevailing one, forms the “paradigm” that guides the sorts of questions scientists ask and

into which experimental evidence is made to fit. With new knowledge, glitches, anomalies, and surprising errors crop up. At first, and routinely so, they’re explained away. But with time, the anomalies accumulate. The old pretty picture grows tattered. Alternative theories contend. And out of it, finally, comes a new way of looking at the facts of nature, a new paradigm—a revolution in form not so different from a political one, that all but die-hard champions of the old paradigm come to accept. What

really

happens, then, in science, said Kuhn, is that some long-prevailing view of nature undergoes, often disconcertingly, a paradigm shift, and the world is never the same again. Think Darwin’s evolution. Think Einstein’s relativity.

And think, with but few apologies to

Death and Life

’s incompletely scientific roots, Jane’s transcendent vision of cities and city life. Her book, observed the historian Mike Wallace in an episode of a Ken Burns video series devoted to New York City, served as “a counternarrative, a counterargument, a countervision of what the city is.” And the counternarrative has taken hold.

Attitudes toward city living have changed;

cities

have changed, and for the better. These days, the virtues of density and walkability are widely enough shared that real estate listings increasingly cite a property’s, or a neighborhood’s, “Walkscore.” This is a database-generated numerical index between 1 and 100 that estimates the ease of buying a quart of milk, say, or doing other everyday chores, on foot; a 90 attracts the

Death and Life

crowd, while a 30 or 40 turns them away. In 2013, real estate researchers meeting in Atlanta declared that America had crossed a threshold—“

peak sprawl,” they called it—meaning that most new construction was now in higher-density, walkable districts.

Meanwhile, walkability, street life, diversity, mixed use, and other words and ideas associated with

Death and Life

now verge on catchphrases, sometimes so thoughtlessly invoked as to mean nothing. “Mixed use” had become “a developer’s mantra,” Paul Goldberger marveled after Jane’s death.

Who could have envisioned the day when politicians and developers trying to sell New York on a gigantic football stadium beside the Hudson River would propose surrounding it with shops and cafes so that they could promote it as an asset to the city’s street life? When that happened in 2004…I knew the age of Jane Jacobs had entered a new phase, the phase that comes when radical ideas move into the mainstream, and can be corrupted by those who claim to follow them. In the twenty-first century, the danger is not with those who oppose Jane Jacobs, but with those who claim to follow her.

Recent years have seen the rise of a New Urbanism, which outwardly embraces some Jacobsean ideas. New Urbanist communities, known for their pretty front porches, nineteenth-century scale, and nod to walkability, normally lack much socioeconomic mix. And built all at once, at relatively low density, under tight regulatory and zoning controls, they rarely include the old, low-rent buildings Jane saw as incubators of urban vitality. Jane “didn’t have much patience with the New Urbanists, whose very philosophy of returning to pedestrian-oriented cities would seem to owe a lot to Jacobs,” Paul Goldberger would report. “She found them hopelessly suburban, and once said to me, with a rhyming cadence worthy of Muhammad Ali, ‘They only create what they say they hate.’ ” More charitably, the New Urbanism could be seen as a small, halting step away from orthodox sprawling suburbs. In it, UC Berkeley’s Roger Montgomery has pointed out, “

the influence of Jane Jacobs lives, misused perhaps, but very much alive in today’s practice environment.”

The preservationist

James Marston Fitch once observed that Jane “wrote as if the urban tissue which she was defending was programmed for automatic repair and renewal, like organic living tissue with its miraculous capacities for regeneration.” So it is happening: in wide swaths of San Francisco, Boston, Toronto, and New York, in smaller but growing patches of Baltimore, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Sacramento, and really everywhere in America and Canada, in-town districts reflecting Jane’s sensibilities have come back to life as bustling, walkable, delightful, and diverse urban places. In his book of the same name, Alan Ehrenhalt describes what he calls a “great inversion,” in which the old postwar pattern of well-off suburbs and poor city centers has begun to turn inside out, with dead, dying, and abandoned malls and decrepit suburban ranch houses flanking cities of rebirth and rejuvenation.

But by now we are getting ahead of ourselves, looking back to

Death and Life

from our time, today, as if Jane had already passed on. In fact, when we left her last, near the turn of the century, she was alive and active, chugging away at her writing. In September 2000, when she was eighty-four, she was interviewed by James Howard Kunstler for a feature

to appear the following spring in

Metropolis

magazine. “You spent really the prime of your life living in Manhattan and Greenwich Village…” he began to frame his question.

“I wouldn’t say that,” Jane interrupted him.

“No?”

No, she chuckled, “I am still in the prime of life.”

In 1997, the year after Bob died, Jane joined the board of Ecotrust, an environmental group with offices in the American West. Across five days that July, Ecotrust’s strategic planning meeting was built around a raft trip down the Salmon River in Idaho. As boulders on the far shore reared up behind roiling white waters, there, nestled in one of the rafts, bundled into a life vest, was Jane, a happy smile planted on her eighty-one-year-old face. “

We’d strap her on the front of the raft every day and she’d go bouncing down the river,” remembered the group’s president. She was chubby and stooped, and

she worried she’d hurt herself getting out of the boat or stumbling on a rock, but she managed, a banged-up shin the only price she paid for the adventure. “She was an unbelievable font of ideas, and funny as a hoot.”

II. ACOLYTES AND APOSTATES

As Jane moved into old age, and even more so after her death in 2006, the respect accorded her sometimes slipped over into veneration, hero worship, or worse. Honorary degrees were offered her, streets named for her, her name invoked as talisman,

Death

and Life

and her other books cited as if holy writ.

She was not wholly immune to blandishments of attention or praise, nor was she above honors, nor averse to accepting awards; she received many. Sometimes these were for specific books, like the Sidney Hillman Prize in 1962 for

Death and Life;

or the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in 1984 for

Cities and the Wealth of Nations;

or, for the same book, the Mencken Award in 1985, named for H. L. Mencken, the cantankerous, libertarian-spirited critic. In 1998, she received a life award from the American Institute of Architects. The awards formula normally included ceremony, citation, dinner, maybe an address of some kind required of her. At the University of Virginia, a five-day round of events included tours, seminars, meetings with students, the Founder’s Day Luncheon

on Friday at the Rotunda (pan-seared chicken with shrimp and farfel; toasted meringue shell with strawberries and rhubarb compote for dessert) and a black-tie dinner at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home, on his birthday.

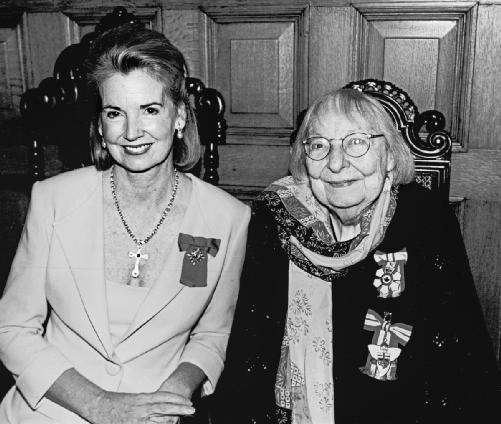

Jane, with Queen Elizabeth’s representative, Hilary Weston, on being awarded the Order of Ontario in 2000. Four years earlier, she had become an officer of the Order of Canada.

Credit 30

Honors like these seemed neither to roll off Jane’s back, leaving her unmoved, nor to go to her head. But by now she had a history going back to the early 1960s, when

Death and Life

and the West Village wars first thrust her into the glary floodlights, of public distractions that pulled her away from writing. These years later, she wasn’t often leading neighborhood battles anymore. But she’d deeply internalized the need to protect her writing time and she often just said no. Back in 1986, named recipient of a $5,000 honorarium for a prestigious lecture in Jerusalem, she replied that, though honored, she just couldn’t accept:

While I can always use more money, really my problem isn’t buying time to work, but rather protecting and taking advantage of the time I do have to get a book written, as well as avoiding the (to me) severely energy-sapping business of switching to something else, then getting all geared up again to concentrate on the difficulties and complexities of my book.

She drew the line altogether at honorary degrees. Someone once totted up the number of them offered her over the years, about thirty. During one span flanking the new millennium, offers came from the University of Toronto, Clark University in Massachusetts, University of Victoria, California College of Arts and Crafts, and Columbia University. She declined them all as false credentials. Besides, she wasn’t much at home with academic ways generally; she rarely attended events at the University of Toronto, just blocks from her house. “

Much as I feel fondly attached to Columbia—which I do,” Jane wrote in reply to Columbia president George Rupp, on December 31, 2000, “it would be awkward and difficult” to alter her stance on honorary degrees. She accepted the Jefferson Medal because it was

not

an honorary degree, but an honor of real substance; past recipients included Mies van der Rohe, Lewis Mumford, and Frank Gehry. Besides, she’d note with satisfaction, her father and brothers all had attended UVA.

By the mid-1990s, scholars and would-be biographers interested in Jane and her work began introducing themselves to her. “

About a year and a half ago I began a journey of research and discovery,” a Harvard graduate student, Peter Laurence, opened his appeal to her in 1999. He was working on a project, “The Jacobs Effect.” He outlined his ideas for it and wondered whether they might meet. They did meet, his work ultimately leading to several serious and original articles and, recently, two books. In 2002, another graduate student, Christopher Klemek, wrote Jane expressing his wish to write “

a comprehensive intellectual biography” of her. He concluded, “If you would have me as a biographer, I welcome your participation to whatever extent you are willing.” He was about the age Jane was, he noted, when, during the 1940s, she’d offered to help a woman named Tania Cosman with her memoir. “I pray this project gets further.” It didn’t, not as a biography, but they did meet, and Klemek went on to write an ambitious, Jane-rich study about the postwar collapse of urban renewal in Europe and North America.

To Klemek and Laurence, both serious scholars, Jane accorded respectful treatment. But to the parade of those approaching her with requests to submit to this, contribute that, or appear here or there, she was not

always so patient. Normally, she found a gracious way to turn down potential time wasters. But sometimes, an inquiry risked liberating her inner crankiness. A woman named Vanda Sendzimir, whose biographer’s chops seemed to extend only as far as a book about her inventor father, wrote a three-page letter that presumed to educate Jane about her own cultural significance: “

Anyone with this amount of sway has a place in history, and that place needs to be given shape, color, shading and voice,” which she volunteered to supply. “I’m ready to jump on a plane and come up and meet you anytime you say.” Don’t bother, Jane wrote back. “My answer is an unequivocal No.” Her own book project occupied her fully. The last thing she was going to get involved in was “somebody else’s writing project, especially one that doesn’t interest me the way my own project does. To tell you the truth, I even churlishly begrudge the time it takes to answer letters.”