Face (24 page)

Authors: Aimee Liu,Daniel McNeill

He handed me a small triangular knife. “If you’re going to eat, you have to work.”

My relationships with men rarely venture into the kitchen, and I was so unsettled by the combination of a sharp blade and

the sudden physical proximity between us that all further thought of Li fled my mind. Fortunately Tommy seemed to know without

asking that I rarely ate or prepared anything more complicated than salad, and set me to work slicing vegetables while he

tended the noodles and pork on the stove. After tacitly establishing our separate body zones within the limited space,

we

worked in companionable silence, and soon the room filled with the smells of garlic, ginger, and peanut oil.

I completed my assigned task and cleared the counter. He filled two glasses with water, placed them with chopsticks side by

side in front of me.

“Do you have the life you wanted?” I asked.

“What?”

“You said your parents lost face because you wanted a different life. Did you get it?”

He sprinkled the noodles with sesame seed and poked them with long cooking sticks. “My rebellion went too far. I had to leave

Chinatown for some time. A cousin of mine in Hong Kong owns this building. At first, that was the only reason I came back.

Then I realized I never wanted to leave.”

“Where did you go?”

“Oh, far, far away.” He handed me two bowls of noodles, pale yellow with bits of meat and jewel-bright vegetables. “Hungry?”

“Where?”

“Hundred Thirty-fifth Street.”

“Exile.”

“You could call it that.” He smiled, came around beside me, and lifted his glass.

“Gan bei!”

“Gan bei.

‘Bottoms up,’ right?” The toast with which my father always launched lunch at the Ming Yu. “I haven’t heard that in years.”

“Welcome home, Mei-bi.” He clinked my glass and drank.

“You’re trying to distract me. Why? What do you mean, you had to leave?”

He ran a hand through his hair as if it was suddenly bothering him, then picked up his chopsticks and rolled them between

his fingers. The pointed tips hovered over his bowl like a dragonfly over a pond. He leaned forward without another word and

attacked his food.

T

ommy and I have been meeting every three or four days, early mornings primarily, before the tourists invade. It is the time

of day I remember best, when I used to feel most at home. The scratch and roll of metal grates going up. The bustle of vendors

receiving their goods. Mothers and grandmothers calling, answering as early sun warmed the bricks of the buildings across

the street. I had no idea as a child how little I knew of the world in which I lived.

The seniors’ center was an equally benign reintroduction. I’ve accused Tommy of luring me with the most approachable faces

in Chinatown. He doesn’t deny it.

“But who said you can only photograph faces?”

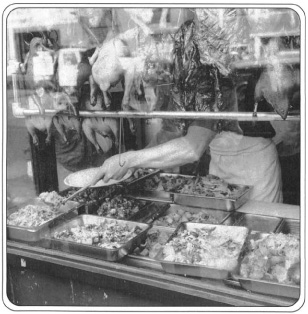

So now, in back rooms and street stalls, I frame swollen hands underwater swimming with fat white noodles, chopping colorless

squares of bean curd, or wielding guillotine cleavers over the heads of squawking ducks. Some of the fingers are gnarled with

arthritis. Others are missing digits. Regardless, they work continuously, automatic as machir

In sweatshops I photograph babies in baskets, their mothers zipping

endless strips of denim through deafening sewing machines. In a shirt-press factory, men stripped to the waist become shadows

in burning fog. In basement meat lockers pale, spindly torsos disappear beneath slabs of pork or beef twice their size, the

butchers’ only visible complaint the curl of their breath in the bitter cold air.

The real complaint lies in their common plan. Twelve or more hours a day at a dollar or two an hour. They save. One day they,

too, will have enough to follow their ABC cousins and buy a nice house out in Queens.

Only Tommy and I are fool enough to come

back

to Chinatown by choice. For the story. The pictures. Some bastardization of memory that helps keep the nightmares at bay.

My dreams have stopped cold. I am getting warmer.

It’s the pictures. There are moments when I imagine my father’s camera pulsing with the images it’s recording, as if it’s

happy to be back in action. As if there really is a connection between Dad’s work and mine. I try to think and not think about

his photographs, let the fact of his accomplishment inform my choices without directing them, but his images and his choice

to destroy them remain at the back of my thoughts. I can’t decide if they’re an invitation or a warning. I believe they are

important.

I’ve always considered the gallery opening to be the art world’s own exquisite form of torture. I realized as a child, when

Mum used to drag me along “for the exposure,” that hardly anyone at an opening bothers to look at the work on the walls. The

reason people attend is to acquire, build, or flaunt social power. And social power within the rarefied world of artists and

collectors is ultimately more important than talent

in

determining status and success. By the time I was fourteen I understood that social power was not something I was capable

of developing, even if I wanted to. That was the year I threw up on Mr, Uelsmann’s photograph (a purely unintentional assault

on one of my mother’s most revered photographic tricksters) and made Mum promise not to invite me to any more openings.

After breaking this promise last month she did not force me to think about it further. No phone calls. No invitations to lunch.

No more coy requests for me to escort her through the badlands of Harlem. And, what with the trips back to Chinatown and the

start of Christmas catalog work for Noble, I managed to put the whole matter out of my head, would perhaps have forgotten

all about it if my brother hadn’t called.

“You know anything about Foucault’s new mistress?”

“Didn’t know he had one.”

“French. Early twenties. A brunette Deneuve.”

“So Mum says, I take it.”

“Well, then, you going to this opening next week?”

“Hadn’t planned to.”

He hummed the opening bar of the

Twilight Zone

theme. “There’s intrigue afoot.”

“I suppose you’re the linchpin?”

“You don’t need to sound so superior. She’s been trying to set you up ever since you got back to New York.”

“And I’ve been fending her off. Anyway, that’s about work.”

“I have a feeling this is, too. So. You coming?”

It was that fast. One second I was bantering with my brother, the next I was exposing a lie. A big one. About work.

The phrase stuck, repeated. My mother’s work. My father’s. A lie that spanned my entire life.

“Henry, have you ever seen any of Dad’s photographs?”

“Huh?”

“His work. You know? Photojournalism. Combat photog?”

“Course not. He destroyed it all before we were born, didn’t he?”

“Far as you know, Mum didn’t have any of his pictures?”

“Not that she ever told me. What’s this got to do with the opening?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Nothing. I’ll see you there.”

It was a Ladies’ Day over twenty-two years ago. I couldn’t have been much more than four. This was before Mum encouraged me

to explore,

said I could only look, not touch, when I came to the gallery. But this day I was up in the third-floor storage room alone

and my crayon rolled under a chest, and as I reached for it my hand tripped a hidden latch. A secret drawer popped open.

I knew I shouldn’t. I should just close the drawer. Maybe if I asked about it, Mum would show me later. But it was too tempting.

This was a secret drawer with hidden pictures. Something about them had to be special. And forbidden.

Ever so carefully, I lifted the layer of tissue that covered the stack and began to look through a set of black-and-white

photographs my mother had never displayed. The white man with the bleeding black baby. The lady with the pig. The tall blond

man looking as though he didn’t even notice that headless body and all those screaming Chinese men. Children dressed in rags

on a street littered with party hats. A city turned into a war zone. The makings of a nightmare.

I was staring at a pagoda like the Chinatown phone booth, only much, much bigger. I had to look close to understand and when

I did I cried out loud. From those pretty, ornate roofs dangled bodies. Men’s naked bodies.

My mother walked into the room.

I pulled in my hands and backed away from the pictures. But she wasn’t even angry.

“What do you think?”

I expected her to punish me. I couldn’t answer.

“Do you like them?”

I nodded.

“How much?”

“A lot?”

“More

than that?” She pointed to a photograph on the wall, of two midgets emerging from a gorilla suit.

I nodded cautiously.

“Why?” she said.

“I just do.”

And then, faster than I could move away, she grabbed me. But she

still didn’t shake or spank me. She hugged me. “It’s no wonder you like these pictures. Your father took them. They’re fabulous.

And they’re just some of the shots that made him famous… But you mustn’t let him—or anyone—know I have these.”

“Why? What would he do?”

“Oh…” She made an ugly face and shook her head so her voice quivered. “Something low-down and mean, I’m sure. You know, he’s

half magic, don’t you?”

“He is! Really, Mum?”

She sighed and let me go. “No, not really. But I mean it about not telling him. If he gets wind of these prints, he’ll destroy

them, the way he did all the others.”

She checked to see that the photographs were lying straight and flat, pushed in the drawer so the lock snapped. Then she twisted

around and took both my hands, flipped them over as if reading my palms. Her fingers were cold and long around mine. She squatted

lower to look me straight in the eye. She had her serious face on.

“You just forget you ever saw these pictures, Maibee.”

“But what are you hiding them for?”

“That’s for me to know and you to find out. But someday, not now. Not for a long time.”