Fairy Tale Interrupted (25 page)

Read Fairy Tale Interrupted Online

Authors: Rosemarie Terenzio

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Bronx (New York; N.Y.), #Personal Memoirs, #Rich & Famous

Liz Rosenberg, Madonna’s publicist.

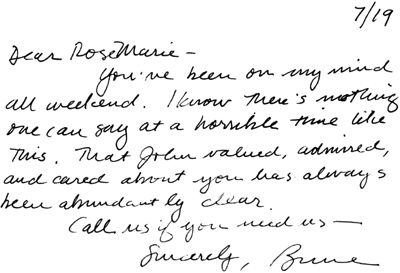

BRUCE TRACY

Bruce Tracy, editor of two books published by

George

magazine:

The Book of Political Lists

and

250 Ways to Make America Better.

TO: ROSEMARIE TERENZIO

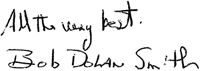

FROM: TERRY and BOB DOLAN SMITH

We haven’t had the TV on since Saturday afternoon when there was still that faintest hope

.

Terry and I know you are grieving but we hope you are taking immense solace in the

quiet

knowledge that you WERE John Kennedy Jr. in so many ways.

It

was your subtle guidance, your consul, and, in the very best sense of die word, your “mothering” which helped die world see the very best John Kennedy. We know how much he relied on you and as scores of lesser outers scramble to the heat of the camera to pontificate on every aspect of a John Kennedy they barely knew, WE, and I am sure many others, know who was really there for John

.

Bob Dolan Smith, a writer for Johnny Carson for twenty years, then for Jay Leno.

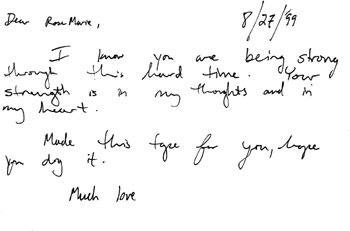

I didn’t think anyone knew who I was, yet all those people, whom knew John well, took the time to send me their condolences. Some more eloquently than others (Joey sent me a mixed tape with a note on a torn-out piece of notebook paper):

Self-pity, which I had yet to let myself feel, expressed itself in silent tears as I continued sorting through the mountain of cards. When the phone rang, any normal person would have let it go to voice mail, but, accustomed to answering, I instinctively picked it up.

“Random Ventures,” I said, even as I thought:

There is no more Random Ventures.

“Is this RoseMarie?” a familiar voice said.

“Yes.”

“Do you know who this is?” he asked.

I wasn’t in the mood for games. “No,” I replied.

“You hear my voice every day on the radio and you don’t know who I am?”

I almost died. It was Howard Stern.

Even after we moved to the Hachette building, I kept Howard’s show on at the office. At first John made fun of me, but soon enough he was hanging around my desk to listen for a few minutes, or if I was laughing at a joke he’d missed, he asked, “What’s Howard talking about today?”

When I first suggested that John put Howard on the cover of

George,

he was skeptical. But I convinced him that Howard had the same mission as the magazine: to bring up important issues by way of entertainment.

Going to the cover shoot was a major perk for me, and John came along—which wasn’t his usual MO—because he knew what an important event it was for me. I was extremely nervous, worse than anything I had ever experienced, even on my first day of work. That was the biggest celebrity moment in my life.

When Howard arrived on set, tall and perfect, Matt Berman brought him directly over to the couch where I was sitting.

“This is John’s assistant,” Matt said. “She’s the reason you’re on the cover.”

I wanted to die right there.

“So I hear you have a crush on me,” Howard said. “You work for JFK Jr. and you have a crush on

me

? What’s wrong with you?”

I didn’t speak or even look at him. I was too scared.

“That’s because Rosie’s a loser,” John said.

“Well, I don’t know about that,” Howard said.

I was so tongue-tied that I couldn’t even tell him about how I excoriated John when I first met him because he had ripped my head shot of Howard. It was all I could do to stand up when he put out his arms for a hug. Then he said, “Will you go on a date with me?”

“Yes, of course I will,” I said in a tiny voice.

When the issue was set to hit newsstands, John decided to go on Howard’s show to promote the cover, because the King of All Media had been the only on-air celebrity who didn’t make his cover participation contingent on John appearing on his radio program. “I feel like I owe it to him,” John said. “He was such a gentleman.” Hachette’s PR people and Nancy Haberman were very distressed, but John told them he could handle it. I was elated.

The morning of the show, Carolyn called me at six, when the program began, and we sat together on the phone listening to the radio.

“I’m so nervous,” Carolyn said.

“So am I.”

“

What?

Don’t say that! I thought you said you weren’t nervous about him going on the show.”

“No, no. He’ll be fine,” I said. I was

really

nervous. Howard had an unmatched ability to make people look stupid.

Howard, a total genius, questioned John about all the taboo topics

and

had his famous guest laughing. He even referenced the “Brawl in the Park,” a videotaped fight between John and Carolyn when they were still dating that had earned a paparazzo a six-figure paycheck and made my life miserable for the entire week it aired on

Hard Copy

.

“You’re dating the hottest chick and you’re fighting? Why

are you fighting with her? Over a dog? If she were my girlfriend, I would say, ‘You want the dog? Take the dog. Take my hand with the dog.’”

Carolyn laughed into the phone and said, “Oh my God. I love him now.”

John was comfortable sitting in Howard’s studio because he and Howard weren’t that different. Both had outsize personas (albeit dissimilar types) and were fundamentally good guys.

“I’m so sorry. What a tragedy,” Howard said to me on the phone the Monday after John died. “If you need anything, you call me.”

Although I appreciated Howard’s sentiment (Howard Stern wanted to help

me

), I was a bottomless pit of need to the point where no one could help. Without John around to protect me, I felt vulnerable. I wasn’t the only one.

That same Monday, Jack Kliger assembled the staff of

George

and addressed

John’s death with all the sensitivity of a serial killer. I didn’t blame him—who was prepared to handle something like this?—but his speech to us was: “We don’t know what’s going to happen with the magazine. I wish I could tell you, but we just don’t know. This is a business, and for now, we have to keep going.” We were still trying to process what had happened over the weekend; nobody gave a shit about the magazine or the state of our jobs.

I didn’t last long at

George

(I was John’s assistant and John was dead), but before I left, I found myself locked in a battle with the publishing company over my severance. Because my executive assistant title was that of an entry-level position, the Hachette HR wanted to give me six weeks of severance. Meanwhile, editors who were part of the mass exodus after John’s death and who hadn’t worked for the magazine nearly as long as I had were getting six months. I might have just taken the money and walked—moved on with my life, even though I felt like I didn’t have one—but when Hachette tried to renege half my bonus because I didn’t work the whole year, I decided to fight (I eventually won, after John’s lawyers got involved).

I stayed through the last issue John had worked on, which we refused to call a tribute because John would have

hated

that. “Oh, brother, people die every day,” I could hear him say in my head.

John had said that if

George

ever folded, he wanted the last cover image to be of George Washington in a coffin, a funny swan song. Matt and I pitched the idea, but nobody was on board. So instead (refusing to put anyone’s image—especially John’s—on the cover), Matt created a beautiful and memorable design in its powerful simplicity: a blurred image of the American flag blowing in the wind. The flag represented

George

and what it stood for—American politics, John’s passion. So we did pay tribute to John, in a way that would have made him proud.

The only other magazine whose cover rivaled

George

’s was

The

New Yorker,

which published an image of the Statue of Liberty with a black veil over her face. When my issue came in the mail the week after John died, I was touched—I always felt that John wasn’t taken seriously enough, and nothing is more serious than

The

New Yorker

.

More than a month after John died, I said good-bye to

George

and entered into a stultifying daily routine that began when I woke up around 11:00 a.m. There wasn’t much more to it than me sitting on my couch drinking coffee, Diet Snapple,

and Diet Coke, punctuated with cigarettes, until my afternoon nap at 2:00 p.m., which slid me into the evening. I didn’t bother to shower or get dressed. It was like having the flu—except it went on for months. Once in a while I went out at night. But in the daytime, not a chance. My biggest fear was being out during rush hour or lunchtime. Surrounded by people hurrying to work or home, I was reminded of what I didn’t have and I panicked. Whereas once I thought my life was charmed, now it felt cursed.

People frequently told me how well I was handling “the situation.”

Really?

I thought.

I don’t want to handle it well

. I wanted to scream like a lunatic in the streets. And many times I considered it. The memory of John—his grace under pressure and assertion that the way people act under horrible circumstances is the true mark of their character—was the only reason I kept it together, on the outside at least.

My fantasy that Tony and I would ride off into the sunset together faded shortly after the funerals were over and the paparazzi had moved on to the next story. He comforted me after John’s service, and together we attended the one for Carolyn and Lauren in Connecticut.

Later in the summer, when Anthony Radziwill passed away from cancer, we were both invited to the funeral at the house of his mother, Lee, in the Hamptons, where Tony also rented a place. When I called him to make plans, I assumed I would stay with him, since he was already out in Long Island. “Let me see if someone has a room for you,” he said, and then never called back.

I knew from that call that our connection was gone, but the weekend of the funeral offered painful proof. I stayed with my

dear friend Stephanie, who worked as Matt Berman’s assistant, and she drove me to the funeral, where Tony was less than attentive. Having held out hope, I told my friend I didn’t need a ride home, so I was forced to find a way back with strangers.

It seemed like everything around me was dead: my career, my love life, my closest friends. And then my dad.

In February 2000, seven months after John and Carolyn, and less than two years after Frank, my dad died of a blood clot that went to his lungs. When Dad passed away, I lost my political sparring partner and the only man who took pride in everything I had accomplished. He’d been in the hospital after breaking his hip and was preparing to return to work. I had spoken to him two hours before he told my mom he couldn’t breathe, and then collapsed and died before the paramedics arrived.