Falcon (21 page)

But politics were no help in re-encountering banded falcons: this required luck, and the resulting migration data sets were inevitably sparse. What everyone really wanted, of course, was to capture the entire spatio-temporal pattern of a migration. So, after experimenting with falcon-mounted radiotransmitters tracked from light aircraft, the idea of miniature backpack- mounted satellite tags was mooted.

One-kilogram satellite transmitters had already been pro- duced by the 1980s: splendid for tracking polar bears and caribou but clearly a little impractical for birds. Joint military-

A satellite-tagged peregrine shortly before release.

university research soon triumphed, however, with a new gen- eration of miniature satellite transmitters. Known as Satellite Platform Transmitter Terminals (ptts), they initially weighed around 200 grams – swan and goose-sized birds alone could carry them. They now weigh less than 20 grams. The ptt is mounted on the bird’s back using a soft, carefully designed, temporary harness. And then the bird is released: its location determined remotely from the Doppler shift in the carrier fre- quency transmitted by the tag as the receiving satellite passes overhead. Service Argos, the French-operated sensor system carried on noaa weather satellites, picks up the signals, and calculations of the bird’s position are conducted at data-pro- cessing centres in France and Maryland – and the Air Force Space Command tracking facility in Colorado provides orbital elements for each satellite.

‘in god we trust: all others we monitor’

25The peregrine migration study rolled into the twenty-first century under the aegis of the us Department of Defense’s ‘Part- ners in Flight’ program, and the private/university/government

CCRT’s logo shows America as a montage of predatory animal gazes.

partnership, the Center for Conservation Research and Technology (ccrt). The Department of Defense is the third largest landowner in the us and is legally obliged to protect endangered animals on its land. Proving grounds and missile- testing ranges are not optimal habitats for roving field biologists, so remotely tracking animals by satellite or radio is a practical solution. Yet monitoring animals in this way has ideo- logical benefits for the us military, too. Back in the 1940s Aldo Leopold introduced the notion of the ‘land mechanism’ in ecol- ogy, metaphorizing ecosystems as complex engines of cogs and wheels. It was a conception of nature fitted to the discourse of technocratic militarism. ccrt biologists describe satellite- tagged peregrines as ‘taste-testers’ discovering ‘hot spots along their route of dangerous pesticides and other threats to sur- vival’.

26

Here the falcon is a biological probe sent out to assess the environment, a hybrid of Predator uav and miner’s canary. And satellite-tagged peregrines are more than mere monitoring instruments. ccrt biologist Tom Maechtle mused on how satel- lite tracking ‘turns the animal into a partner with the researcher’. ‘You can think of a peregrine as a biologist who has been sent out to find and sample other birds’, he explains.

27Maechtle’s words are familiar: once again, here is a falcon biologist identifying strongly with his subject, just as the Craigheads saw their young, adventurous field-biologist selves mirrored in the eyes of the peregrine. And

Los Angeles Times

science writer Robert Lee Hotz is at pains to point out that this new kind of science doesn’t threaten the old ways. Not all modern biologists stare at computer screens under fluorescent strip-lights, listening to the hum of climate control instead of birdsong. ‘Despite these advanced tracking technologies’, he writes, ‘the biologists . . . still must catch the birds by hand.’

28

The social identity of the adventurous field biologist isunthreatened by satellite tracking. Stamina, field-craft, practi- cal skills: these are all still required. And thus, high technology and global vision are linked with individual heroism and the soul of the wild frontier.

A heady mix. For while their conservation benefit is unar- guable, the inner logic of these defence-funded tracking efforts is breathtaking. As each individuated falcon is tracked across global space, it carries far more than simply its location. ccrt calls the tagged bird a ‘sentinel animal’. Each symbolically extends us technological and military dominance even as it offers myths of ‘one world’ environmentalism: global surveil- lance systems track ‘American’ falcons as they penetrate airspace as far south as Buenos Aires and the headwaters of the Amazon. These augmented falcons join together two incom- mensurable worlds – those of

military

/

war

and

nature

/

peace.

These concepts seem naturally opposed, but the satellite-tagged falcon closes the divide. The myth of falcon-as-warplane meets the myth of falcon as unparalleled symbol of wild nature, the tagged falcon a halfway house between the two systems of nature and culture, between national defence and the defence of national nature. One might see the satellite-tagged falcon as an ultimate naturalization for the military, which not only defends nature, but also promotes the notion of an ecosystem as just another complex technological system, something entirely integratable into c4isr systems.A new generation of bird-borne ptts will carry advanced sensors to detect speed, temperature, humidity and atmos- pheric pressure, digital audio capture systems and even miniature video cameras. Sound familiar? Over the past few years, developments in us military unmanned aerial systems have produced tiny Kevlar and carbon military drones that hover or fly hundreds of feet above the battlefield, tracking

military vehicles and sending live video feeds to the laptops of unit commanders. And in Idaho military training grounds, ccrt has satellite-tracked raptors in conjunction with the Deployable-Force-on-Force Instrumented Range System (dfirst) to demonstrate the feasibility of integrating automated military tracking systems with natural resource management technology, simultaneously tracking the movement of raptors and military vehicles. The bird is tracked as an object in a system of objects. And those other objects happen to be military.

Indeed, in Alaska, the us Air Force has designated peregrine nests as surface-to-air missile sites. ‘By designating known nests

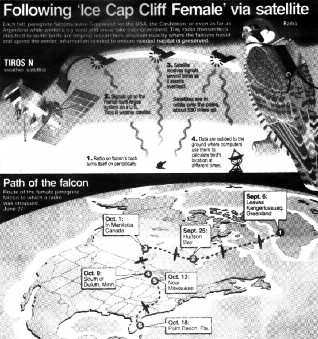

Strategic Air Command meets Animal Planet:

a graphic of the travels of a satellite-tagged falcon.

as simulated “threat emitter sites (areas that pilots must avoid as part of their routine training program)”’ reports explain, ‘the Air Force has continued realistic training while simultaneously protecting nesting peregrine falcons. This species is now recov- ered.’

29

The wording is highly ambiguous, suggesting that by including peregrine nests on TacAir training maps, the usaf has defended and saved the peregrine. In terms of one particular strand of falcon iconography, that might very well be true. Nature and the military achieve a discursive equality – they become symbolically equal when their positions are read through battle software, on a battle map. Defending the falcon

is

defending the nation. Attila would have been proud.- Urban Falcons

Even in a big city, the falcon’s world is different from man’s, and the two converge only at rare moments when we humans make a special effort to meet the falcon on her own terms.

1

You share airspace with the peregrine over London in Charles Tunnicliffe’s 1923 woodcut, and its aviator’s vantage too: that sense of power over, and separation from, the city below. And you and the falcon both possess that other ferociously modern ability, to set yourself against the sweep of history. Here is Roger Tory Peterson, writing in 1948:

Man has emerged from the shadows of antiquity with a peregrine on his wrist. Its dispassionate brown eyes, more than those of any other bird, have been witness to the struggle for civilisation, from the squalid tents on the steppes of Asia thousands of years ago to the marble halls of European Kings in the seventeenth century.

2

One of the less obvious roles of wild animals is to signify his- tory. They can do so because they are perceived as immortal. Clearly, animals aren’t immortal in the physical sense, and nor is this the animal immortality espoused by academic theoreti- cians, among whom at least one thinks that animals are technically immortal because they possess no language.

3

This form of immortality rests on a far more straightforward phe- nomenon: that a falcon is a falcon. The same falcon. Whenever it’s lived, wherever it is. A fourteenth-century gyrfalcon is as

Other books

The Rules of Magic by Alice Hoffman

Kiss Me by Kristine Mason

Islas en la Red by Bruce Sterling

The Human Comedy by Honore de Balzac

Bilingual Being by Kathleen Saint-Onge

The Godling Chronicles (Shadow of the Gods, Book #3) by Brian D. Anderson

The Rise of Vlad (The Seeker Series Book 3) by Ditter Kellen

The Alpine Journey by Mary Daheim