Faldo/Norman (28 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

It is not that his results have not been consistently high at the Masters since his last win; even when he is not playing well he has an ability to get the ball round the course in a tidy score. He was third in 2006, second the next two years, sixth in 2009, fourth in 2010, when the Masters was his first event of the season, and fourth again in 2011. Some of those years he had a chance to win, some of them he did not. In 2012 he certainly did not and finished tied for 40th place. In 2013, he had just got himself to the top of the leaderboard in the second round when his third at the 15th hit the flagstick and rebounded into the pond. He then took an incorrect drop and what initially went down on the card as bogey six turned into an eight overnight. He was lucky not to be disqualified for signing for an incorrect score had not the Masters rules committee admitted its own error in not confronting Woods about the incident in the recorder’s hut.

Woods struggled that weekend, a common thread throughout his major performances in recent years, and finished four behind Adam Scott and Angel Cabrera. Two things have stopped Woods from getting nearer the tally of 11 green jackets predicted by Nicklaus and Palmer. His putting has not been as relentlessly reliable as in his earlier days but he has also put more pressure on it with his more erratic long game. In particular, with all the extra length at Augusta, driving the ball well is still a prerequisite. Woods has to hit the driver, which he tries to keep in the bag as much as possible elsewhere, and when he takes it out he fears the ‘Big Miss’, as his former coach Hank Haney calls it. Once, from the 1st tee at Augusta, he found the 8th fairway, waving to the 1st and 9th fairways plus various pines on the way.

And time marches on. He will be 38 at the 2014 Masters, the same age that Faldo won his third jacket, three years younger than when Norman had his best chance of joining the elite club. Neither contended nearly as often again as they imagined.

Woods was once asked if he felt it was strange that Norman was not able to enter the champions’ locker room at Augusta? ‘I do. It’s amazing, for someone who’s had such a great career and come so close, you almost feel like he has won the tournament, even though he hasn’t, because he’s been there so many times and especially on this golf course because it sets up so well for him. It’s hard to believe he’s not in the locker room.’

Hole 15

Yards 500; Par 5

A

S THE LAST

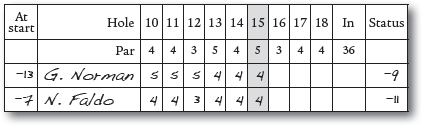

par-five on the course, the 15th hole offers a final chance to make a big move. Often it rates as the easiest hole (against par) of all at Augusta, although there is still plenty of danger to create another fine example of the risk-reward nature of the back nine. As Nick Faldo and Greg Norman teed off there was another small reminder of why it has been one of the most dramatic holes in golf since the very start of the Masters.

Playing ahead of the final pairing, Phil Mickelson, following a typically erratic spell in which he bogeyed the 12th, birdied at the 13th but bogeyed again at the 14th, made an eagle to jump back up to six under par. He was again now sharing third place with Frank Nobilo, two behind Norman and four behind Faldo. It was a textbook three, which is to say it was most un-Phil-like – a drive down the middle and an approach to the middle of the green before he added the characteristic flourish by holing the putt from 20 feet.

In fact, in 1996 the 15th played as only the fourth easiest hole on the course and among those helping to bump up the average was Colin Montgomerie. After his triple-bogey eight on Saturday he had another ‘snowman’ on Sunday. He played those

two holes in six over and the other 70 in only two over par. He had laid up short of the pond in front of the green on Saturday so on Sunday he went for it in two. However, his three-iron clipped a branch and came down into the water. His next ran back down the bank in front of the green and back into the water. ‘GOD. THIS. BLOODY. PLACE’ gasped the world number two. He finished tied for 39th place, alongside Vijay Singh at eight over par, and ahead of only four other players who made the halfway cut: Jack Nicklaus, Steve Lowery, Seve Ballesteros and Alex Cejka. ‘I’ve been coming here five years and I’ve not had an eagle and my best score is 69. I just can’t get going.’

Augusta National was never a happy hunting ground for the Scot, but then nor was American golf generally. He never won on the PGA Tour but it was at the other two majors in the States that he had some of his cruellest near misses, particularly at the US Open. And he took some fearful stick from the galleries, particularly after being dubbed ‘Mrs Doubtfire’ by hecklers at Congressional in 1997. But the likes of Montgomerie and Lee Trevino, who could not get on with the course either, tend to be in the minority. Most players love the Masters. They may not love the fact that certain things on site are done differently to what they are used to at regular tournaments but they put up with that just to have a chance to play at Augusta.

And the chance to play in the Masters is not given to everyone. Fewer than 100 players get to contest the tournament each year. Qualification is like a longed-for Christmas present and the treasured invitations, for the first batch of qualifiers, arrives on the doormat around about that time of year. Part of the mystique is giving an invitation to every player who wins on the PGA Tour, so much so that when the qualification was dropped for a few years a part of the romance went with it. First-time winners on tour, or perhaps a veteran who has not got to play at Augusta in

a while, value the ticket for the Masters as much as the oversized cheque with a long string of zeros. In the run-up to the tournament, players who have yet to qualify still have that last chance by winning that week. It makes defeat doubly hard to bear, as Ernie Els found out in 2012 when he had to sit at home – although three months later he solved the problem by winning the Open at Royal Lytham and earning a Masters exemption for five years.

No one quite knows how or why the Masters became a major championship in golf. It just happened, largely on the basis of knowing it when you see it. In 1950, Jimmy Demaret, who never won a US Open or a US PGA and finished tenth on his only appearance in the Open, became the first player to win the Masters for a third time and declared it the ‘greatest championship in the world. Bar none!’

It helped that the best players won the Masters so it was obviously a major deal: in 1951 Ben Hogan won the Masters for the first time, the next year Sam Snead won for the second time, and the year after that, in 1953, Hogan won again (he also went on to win the US Open and the Open Championship, and is still the only player to win all three in the same season). The year after that, Snead won for a third time in a playoff over Hogan.

Arnold Palmer, whose charisma leapt out of the screen when golf was televised regularly for the first time, won four times in eight years and the game’s new Big Three – for Byron Nelson, Hogan and Snead read Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player – cleaned up every year from 1960 to 1966. Player went on to win three times, Nicklaus a record six. Tiger Woods joined Palmer on four wins, Mickelson joined Demaret, Snead, Player and Faldo on three. The best players of each generation kept winning the Masters.

In 1960, Palmer had won the Masters and thrillingly claimed the US Open at Cherry Hills, overcoming the still amateur Nicklaus and the veteran Hogan, and on the plane over to

Scotland for the Open at St Andrews got chatting with his friend, golf writer Bob Drum, about recreating Bobby Jones’s Grand Slam. The modern professional equivalent, they quickly came to the conclusion, was the Masters, the US Open, the Open and the US PGA. And it has stuck ever since.

Yet when Jones heard a commentator at the Masters refer to it as a championship one too many times, he snorted: ‘A championship of

what

?’ To Jones, whose inclination was to dislike the name ‘Masters’ in the first place, it was always a tournament and not a championship. Fair enough, but everyone believes the winner is a major champion, and therefore it may only be the Masters Tournament but each year it provides a Masters champion.

Jones himself is the first reason the tournament has always been so highly regarded, even four decades after his death. He died in 1971 of an aneurysm after 23 years of living with syringomyelia, a degenerative disorder caused by a cyst destroying the spinal cord. He was named ‘President in Perpetuity’ of Augusta National. He founded the club after retiring in 1930 as the greatest golfer the world had ever seen who did not play the game professionally. He won the US Amateur five times and the British Amateur once, and against the best professional players of the day, including Walter Hagen and Gene Sarazen, he won the US Open four times and the Open three times.

He did not play many tournaments in a season but when he did it was under the pressure of being expected to win. Usually, he did. The lawyer from Atlanta was the most understated national hero. Hogan said of him later in life: ‘The man was sick so long and fought it so successfully I think we’ve finally discovered the secret of his success. It was the strength of his mind.’

When the Augusta National Invitation Tournament was first played from 1934 onwards, his friends, who happened to be the best golfers around, came to honour the Emperor. They still do. A quarter of a century after his death, just before the 1996 Masters,

Golf Digest

published an extract of an Alistair Cooke essay from

The Greatest of Them All: The Legend of Bobby Jones

. ‘Because of the firm convention of writing nothing about Jones that is less than idolatrous,’ Cooke concluded, ‘I have done a little digging among friends and old golfing acquaintances who knew him and among old writers who, in other fields, have a sharp nose for the disreputable. But I do believe that a whole team of investigative reporters, working in shifts like coal miners, would find that in all of Jones’s life anyone had been able to observe, he nothing common did or mean.

‘The sum of what can be said about his character, by me at any rate, is: that he was an incurable conservative frequently shown in the company of tycoons (more their photo op than his), which led to his reputation for gregariousness (‘They say I love people, but I don’t love people, I love a few people in small doses’); that he was a weekend golfer who rarely touched a club between October and March; that he showed a famous early streak of temper at St Andrews when he was 19 for which he proffered “a general apology” on the spot and was ever afterward restrained. In his instincts and behaviour he was what used to be called a gentleman, an ideal nowadays much derided by the young and liberated.

‘What we are left with in the end is a forever young, good-looking Southerner, an impeccable, courteous and decent man with a private ironical view of life who, to the great good fortune of people who saw him, happened to play the great game with more magic and more grace than anyone before or since.’

Jones was persuaded to play in the first few Masters and kept going until 1948 but never finished higher than 13th in the first year. His magic had gone but he had imbued it in his golf course.

That became clear as early as the second year when Sarazen made his famous albatross and made headlines for the tournament around the world. With Craig Wood leading in the clubhouse on six under par, Sarazen had to play the last four holes in three under to tie.

‘Paired with Hagen,’ Charles Price described in

A Golf Story

, ‘Sarazen elected to go for the green at the par-five 15th, ignoring the water in front of it. Hagen smiled and shook his head. But if Sarazen were to get any birdies at all, one of them would have to be here. There were not more than a dozen spectators by the green, one of whom happened to be Bobby Jones, who had wandered down from the clubhouse out of curiosity, possibly because of the friendly rivalry between Sarazen and Hagen. It was an interesting pairing apart from the tournament, now that it was all but formally over.

‘Sarazen had started to choose his three-wood, but changed his mind to the four-wood before he pulled the three of out his bag. He then stepped into the shot with that one-piece swing of his, like a coach hitting fungoes to an outfielder. The ball struck the far bank of the water hazard abutting the green, skipped onto the putting surface, and softly rolled into the cup for a two.’ The albatross, or double eagle, was the first at Augusta and there has now been one, and only one, at each of the par-fives. No one has since played a hole in better than six under for the tournament, as Sarazen did then, though in 2010 Woods did it at the 15th and Mickelson at the 13th, both with two eagles and two birdies.