Faldo/Norman (30 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

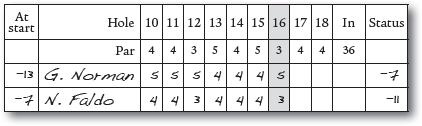

Faldo popped in his putt for a birdie and Norman followed suit. As at the 13th, Norman had done his bit by birdieing the hole for the fourth successive day. Faldo, who played the 15th in two pars and two birdies for the week, had matched him again, however. There had still only been one hole where Norman had gained a stroke on Faldo and that was back at the 5th. Faldo was on 11 under, Norman was 9 under par. There had been no Sarazen magic for the Australian this time round.

Hole 16

Yards 170; Par 3

W

ITH THREE HOLES

to play, just one water hazard stood between Nick Faldo and victory at the 60th Masters. Alas, the pond at the 16th also needed to be cleared by Greg Norman in order to avoid total capitulation. It was not to be. For all that the scorecard said there had been nothing to split the pair over the previous three holes, Faldo had matched the Australian’s two birdies at a time when Norman needed a big swing in his direction. Faldo had sensed how critical it was not to let Norman regain any momentum at the par-fives. By covering his opponent there, not giving an inch, his reward was a doubling of his lead from two to four strokes at the 16th. With a six-iron to the heart of the green, safely above ground, the job was done. Ladbrokes in London had Faldo 1-4 and Norman 11-4 after the 15th hole. After the 16th, they closed the book.

The last question at Norman’s press conference that evening was to ask when he finally realised that it was not going to happen this year? He said: ‘16.’ What else could he say?

What he really meant was the start of the 16th hole, not the end. He later admitted to Lauren St John that he knew it was over after the chip at the 15th had not gone in the hole for an eagle.

He was about to commit one of golf’s cardinal errors – still thinking about the shot before the one you are actually playing.

After dropping five strokes in four holes, from the 9th to the 12th, Norman responded in the only way he knew how, by going in search of birdies. A two-shot deficit with six holes to play at Augusta is nothing. He was able to pick up a couple of birdies, but they did not do him any good. Had his chip at the 15th gone in for an eagle, who knows what that would have done to Faldo? There might have been a two-shot swing there and they would have been level. But it did not happen. It was a brilliantly played shot and he had just played his best sequence of holes of the day but he could find no encouragement.

In her biography of Norman, St John quoted him as saying: ‘I hit the most perfect shot. I put all my energies into it. I visualised it. Everything I know that I’m good at – feel, not executing till you are ready to go. And then when it didn’t go in, I thought, “Oh, shit.” Then Faldo hit a great shot, too, so I didn’t even make up a shot. So that’s when I knew. And the next shot was indicative of the emotions going out of my system.’

A stream that cut in front of the 16th green was transformed into a pond in 1947 and nearly 50 years later it claimed one of its most celebrated victims. The pond covers the front and left-hand side of the green and the tee shot, due to the angle, is played all the way over the water. On practice days, players entertain the gallery by skimming shots over the surface of the pond, doing a ‘Barnes Wallis’, earning a cheer if a ball skips up onto the green, a groan if it runs out of pace, dies and sinks.

The pin was on the back-left portion of the green. One of the three bunkers around the green protects the back-left section from the pond but Norman’s tee shot was so far left that it missed not just the green but the sand as well. It was the most awful-looking thing and Norman’s eyes only tracked its path for

a fraction of its flight before he ducked his head so as not to see the inevitable splash. ‘I just tried to hook a six-iron in there,’ he said, ‘and I hooked it all right.’

Suddenly the brief spark of energy the gallery had tried to instil in Norman had dissipated. Everyone was stunned. Even Faldo lowered his gaze and scratched the back of his head as if trying to figure it all out. ‘It was a riveting unravelling,’ wrote Gary Van Sickle in

Golf World

(US). ‘You didn’t want to watch but you couldn’t stop watching.’

A deathly hush descended. As the

Philadelphia Inquirer

stated: ‘If you took any pleasure at all in witnessing that then your heart is as hard as a tombstone.’ Bob Verdi wrote in the

Chicago Tribune

: ‘It’s quite a feat, strangling yourself in broad daylight while also attempting to swing a golf club.’ The

LA Times

’s Jim Murray added: ‘There is only one golfer on the planet that can regularly beat Greg Norman in a major tournament. That’s Greg Norman.’

Norman walked forwards, swinging his club round and in front of him along the ground to clean the clubface of any debris. He dropped another ball and hit his third to ten feet, a fine shot under the circumstances but too little, too late.

The traditional Masters Sunday pin at the 16th is very accessible for a hole-in-one; Ray Floyd did just that earlier in the day. He hit a five-iron up the right side of the green, the ball beginning to run out of steam once it was level with the hole and then took a sharp left-hand turn, accelerating down the slope and making a sideway entrance into the cup. ‘I aimed at the TV tower and it never left the line,’ he said.

‘When it first landed, I thought it would stay up on the right. But it got closer and closer, it teetered and teetered, and then there was this crescendo from the crowd, they could see the line. I saw beer, sodas and sandwich wrappers go flying. That’s when I knew it went in. It’s my first hole-in-one here. It’s a nice memory

to take home.’ It was the seventh hole-in-one at the 16th in the Masters. It took eight years for there to be another one but then there were eight in nine years.

Faldo’s tee shot at the 16th was on the same line as Floyd’s but it was not long enough to reach the hole. Instead it rolled down the slope from right to left, leaving him a 20-foot putt for a birdie, the most straightforward putt on an otherwise complex green. He would not admit it until the final green but the worst was over now. He would have to do something spectacularly bad to lose it from here.

Norman had already done that for him. As he had stepped up to the tee, Frank Nobilo was being interviewed by Steve Rider on the BBC coverage, saying, ‘I saw Greg on the range this morning. He is bleeding. He is honestly bleeding. His expectations are as high if not higher than everyone else’s for him. He is in a totally unenviable situation. No one would like to be in this situation on this tee right now, blowing a six-shot lead. He’s got to come up with a great shot but, saying that, he is probably the one guy who is capable of it.’

After the tee shot, the commentators threw it back to Nobilo, who added: ‘Obviously, Greg’s had a few bad tee shots today. It’s not an enviable tee shot, when you look at where the pin is, all you really see is the right-hand edge of the trap and you have to hit all the way across the water. Normally, it’s a very makeable shot for Greg. You have to feel for the guy. Right now, he is going through purgatory.’

Two putts from each man brought a par for Faldo and a double bogey five for Norman. Faldo was still at 11 under for the tournament, four under for the round, Norman had slipped back to seven under for the tournament, six over for the day.

Purgatory is what Australians call getting up early on a Monday morning to watch the Masters. It is a long history of disappointment. In 1950, Jim Ferrier led with a round to play but lost by two to Jimmy Demaret after dropping five strokes in the last seven holes. Ferrier started out as a sportswriter who was a successful amateur golfer, winning four Australian Amateur Championships and the Australian Open twice. He then emigrated to America, turned professional and won the US PGA in 1947. But he never prevailed at Augusta, with seven top-seven finishes in 15 appearances.

Bruce Crampton was another Australian who based himself in America. He did not drink or smoke and played every week, in 1964 missing only one tournament when his golf equipment was stolen. He finished second in four major championships, each time to Jack Nicklaus, including the Masters in 1972.

Peter Thomson, Australia’s most successful major winner with his five Open Championships, played only eight times in the Masters, with a best result of fifth in 1957. He was a master of fast-running courses, imaginatively controlling the ball on the ground, but enjoyed less the game through the air and only spent a small part of his career playing in America. A feeling in that country that he was overrated fuelled a brief but devastating spell on the US Seniors Tour, when he swept away all before him, only to return to other matters such as golf writing and course design.

Kel Nagle won the centenary Open at St Andrews in 1960, stopping Arnold Palmer picking up the third leg of a potential Grand Slam, but in nine appearances at Augusta his best finish was 15th. Jack Newton earned a share of second place at the 1980 Masters with a last round of 68, finishing four adrift of the runaway winner Seve Ballesteros. As well as Norman’s assaults in the 1980s and 90s, Craig Parry was the third-round leader in 1992.

But little went right on the final day and a 78 left ‘Popeye’ in a tie for 13th, seven behind Fred Couples.

More recently, in 2007, Stuart Appleby led by one from Woods and Justin Rose but a closing 75 dropped him to joint seventh, four behind winner Zach Johnson. And then in 2011, Australia had two runners-up for the price of one as Adam Scott and Jason Day both had their chances to win only to be pipped by Charl Schwartzel birdieing the last four holes to win by two.

Norman’s three runner-up finishes at Augusta put him alongside Floyd, Tom Watson, Tom Kite and Johnny Miller, and one behind Ben Hogan, Nicklaus and Weiskopf. Weiskopf, Miller and Kite never had the compensation of winning the thing either. During the closing stages of the 1986 Masters, Weiskopf was asked on television what was going through Nicklaus’s mind during his late charge and the 1973 Open champion admitted that if he had any idea he might himself be wearing a green jacket.

One of the consolations that Norman held on to after his 1996 debacle was that he still had ‘a lot more tournaments to play here’. He would get another chance to win the Masters. He did, indeed, play in each of the next six years, and then again in 2009, but the clock eventually runs out for anyone who does not earn a lifetime exemption by becoming a champion.

After missing the cut the intervening two years, in 1999 he was back in the thick of it despite having undergone shoulder surgery the year before. José María Olazábal led after the second and third rounds but Norman was the sentimental favourite. On the Saturday, he overshot the green at the 12th into the flora on the bank behind and, after a frantic search, had to declare a lost ball. He walked back to the tee, put his tee peg right next to the divot from the previous shot, took aim exactly as before and this time fired the ball onto the green. When he holed the putt for a bogey the place went wild. It was the sort of roar Amen Corner

reserves for Sundays. ‘Is it from 1996 or just because I’m getting old?’ Norman said later when asked about the outpouring of support from the gallery.

The Shark added: ‘What happened here in 1996 changed my life. There is a huge amount of support out there from people on a global basis. My locker is full of letters this week. So you still get people writing to you from 1996. You can roll it into what happened last year with the surgery, roll it into the fact that you get to see and appreciate other things in life more than just the game of golf.’

On the Sunday in 1999, Norman was once more playing in the final pairing, starting out one behind. The vital moment came at the 13th, when Norman holed from 25 feet for an eagle but Olazábal managed a birdie from 20 feet to stay level. Norman then bogeyed the next two holes and the Spaniard’s nearest challenger was now Davis Love, who chipped in at the 16th to get within one. Olazábal had watched it happen from the tee and responded with a six-iron to three feet. Norman hit it to six feet but missed the putt, whereas Olazábal holed his. Short it may have been, but the degree of difficulty was extreme. ‘You can’t imagine what a three-footer that was,’ Olazábal said. ‘Downhill and lightning quick with a left-to-right break. I don’t know how the hell I made that putt.’