Falling to Earth (23 page)

Authors: Al Worden

Gradually, we learned to take emergencies in stride. The more we trained, the more we instinctively knew what to do when something went wrong. Although the training was still insane, we got on top of it and in control of it, so there was far less excitement when a red warning light came on. We trained for disaster. A normal flight should be a piece of cake.

The public, of course, only saw the end result: our flight in space. A good equivalent would be watching a football team play a game or attending a concert by a noted pianist. In both cases, you see the well-practiced finale. What you don’t see is the backbreaking hard work and the endless training it takes to get to that level. When the time came to give our performance in front of the world, we would be as polished as athletes and musicians on their big day.

Our mission could not afford to fail. We knew that many in the scientific community were distraught that the Apollo program was being scaled back just as it reached its full scientific potential. We also understood that we would be pleasing the scientists we worked with by performing more experiments. Yet that wasn’t our main reason to do the experiments. The pressure to carry out more science came strictly from within our crew. I not only wanted to do as much as possible personally, but also I never wanted Dave Scott to be in a position where he could say I wasn’t doing my job. Dave was becoming increasingly fascinated with geology as well and piled on his own share of science tasks to attempt. He and I became quite competitive in our scientific preparedness and the number of experiments we planned to fit in. Compared to prior Apollo flights, we really loaded ourselves up with chores.

I think a little bit of competition between us was a good thing. It was an extra incentive for us both: I wasn’t going to let anything get by me, and neither was Dave. We didn’t necessarily have to love working with each other to make a good team. In fact, the competitiveness made us do more. With Dave, I never felt I could say, “I’m a little tired. Can we stop for today?” I was not going to put myself in that position with him, and that working relationship made me do more than I might have done if I’d had a close buddy for a commander.

We accepted more and more science experiment proposals for our flight plan. If everything went smoothly, we’d end up doing more science than any other Apollo mission. Our philosophy was that it was easier to accept a proposal and then not have time to do it in space, than to add a new experiment during the flight. We jammed the flight plan with tasks.

Originally, I expected that during the mission we’d have to throw out some plans as too ambitious. As our launch date grew ever closer, however, I realized that neither Dave nor I would scratch a single science experiment. We’d become so competitive, we didn’t dare. We were a little overloaded and were going to be busy every second, but Dave and I would do all of the experiments because that was the kind of relationship we had with each other.

We had taken our geology training seriously. So seriously, in fact, it made me wonder what Deke Slayton thought. Deke was not a science kind of guy. He was a pilot through and through and didn’t care too much about rocks. Nevertheless, Dave submitted our training program to him for approval. Whatever his personal opinions, Deke agreed to everything we asked for. If he had any concerns about the amount of science we planned on top of all the piloting, I never heard it.

In the meantime, other engineers prepared the equipment we’d use for this ambitious flight. Although I wouldn’t be driving it myself, I found the work on the lunar rover fascinating. The rover was designed to address a fundamental need: without some kind of vehicle, astronauts would not be able to explore as much of the moon’s surface. But the rover wasn’t the only design that had been put forward.

During one of my visits to North American Aviation, I remember talking to some of the engineers over lunch, and they mentioned something fun they had out on the backyard that I could try if I wanted. When I agreed, they took me to the most bizarre flying vehicle prototype I had ever seen, a small, flat, circular platform, with a four-foot pole sticking out of the top. On the top of the pole was a set of bicycle handles, looking a little like a pogo stick. The engineers put me in a protective suit, strapped me into a safety harness, then asked me to stand on the platform and grip the handlebars. They quickly explained that one handle had a throttle control, and when I twisted it I would activate an air hose that blew down at high pressure from under the platform, counterbalancing my weight. It would probably be unstable, they warned me, so the harness was there in case the platform started to tip over.

I turned the throttle control and, wow, that thing was a kick! It took a lot of getting used to, trying to balance on a carpet of air as I revved it up and slithered and shimmied around. The vehicle was possible to master after some practice, but it took skill. With no control system to keep the platform stable, I had to use my natural instincts to stay upright. It was tough but great fun to fly.

Sadly, it was just a rough prototype of an idea, and nothing like that ever flew to the moon. It would have been a great experience to fly over the lunar surface surveying large areas much faster than walking would allow. But the budget cuts that whittled away the Apollo program meant NASA abandoned ambitious plans such as lunar flyers. Fortunately the lunar rover idea survived, although in a stripped-down, basic version of earlier designs. We also had to wait until the end of 1969 for the green light to develop and build the final version.

The Boeing Company had only about eighteen months to design and build the first car to drive on the moon. It was a crazily short amount of time to come up with something so innovative, especially since the lunar rover needed to fold up like a pretzel on the side of the lunar module for the journey to the moon’s surface. When it reached the moon, the rover had to be unfolded again and ready to drive in a short amount of time. It amazed me how fast Boeing came up with a working vehicle.

But not everything went smoothly. I distinctly recall one time that Boeing was having a real problem getting the rover’s electrical system to work. Fortunately, General Motors was Boeing’s prime subcontractor for the vehicle, and the astronauts had some great contacts within that company because of our Corvette deal. On this occasion a discreet phone call was made to Ed Cole, the president of General Motors and a good friend, describing what was not working. He immediately understood the seriousness of the problem and what needed to be done. The prototype car underwent some General Motors tests that Boeing may not have thought to do, and soon afterward the problems were fixed. Although NASA managers generally frowned on astronauts being cozy with the captains of industry, on occasions like this our personal relationships helped move the program forward and cut through a lot of red tape.

Our crew with full-size mockups of the lunar rover and lunar module

But the rover was of more concern to Dave and Jim. They would be the ones driving it on the surface, so they spent a huge amount of time together training with it. There were other new pieces of equipment that directly affected me, and I wanted to focus my time on them instead.

The Apollo service module had been modified after Apollo 13 to make it much safer. I’d had a number of conversations about it with Jack Swigert, while the engineers and technicians tried to work out what had gone wrong on his mission. Jack had followed the flight plan to the letter, and yet an oxygen tank had exploded. The two of us had worked hard on the spacecraft’s malfunction procedures, so we were concerned that a normal procedure might somehow have caused the damage. It was almost a relief when we learned the oxygen tank had an undetected flaw: an easy fix. There was nothing that Jack could have done to prevent the explosion.

For Apollo 15, there would be even bigger changes to the service module. While I orbited the moon alone, I would operate an entire bay of instruments built into the side of the service module. We called it the SIM bay, or Scientific Instrument Module, and it contained a huge amount of scientific equipment to study the moon in great detail. For example, I would have two different cameras to extensively photograph the surface. A high-resolution panoramic camera would take long, thin photos, capturing objects as small as three feet on the lunar surface while I flew overhead. I also had another, wider-range camera that I could use to help cartographers create a detailed map of the moon. To help calibrate the photos, a laser beam would fire at the surface so we could tell exactly how high up I was, and therefore the distances and feature sizes in the photographs.

I would also have instruments that could detect gamma rays, alpha particles, and X-rays, all of which could tell us a great deal about the composition of the moon’s surface. If volcanic gases were also still escaping from the moon, even in minute quantities, we should be able to measure them. When added to the photographs I would take with a handheld camera through the spacecraft windows, I would be an independent scientific laboratory, able to gather data on the moon from above like no human ever had before. At the end of the mission, I’d even get to launch a tiny satellite, which we would leave in lunar orbit to continue making discoveries.

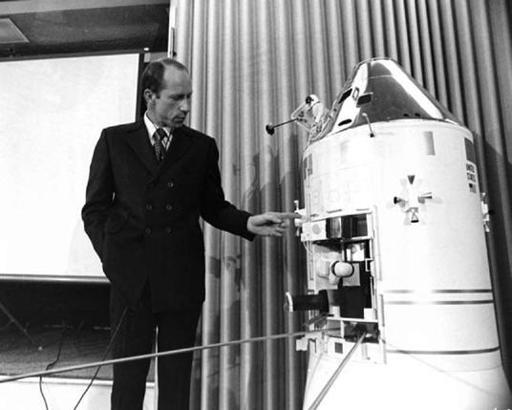

Explaining the SIM bay operations to the press using a model of the command and service module

It was exciting stuff for me and for the scientists who hoped to unlock more of the moon’s secrets. We were moving into far more complex areas than previous missions, doing work that at times sounded more like science fiction. Soon I would be skimming across an alien world, studying and recording it in huge detail. I couldn’t wait.

I worked with the scientists who designed the SIM bay experiments and with the flight planners who integrated our activities into a flight plan with an organized timeline. We ensured that my orbital operations fit well with the surface work, not just in an operational sense, but also in a scientific sense. It would be a powerful combination: Dave and Jim collecting rocks on the surface while I recorded the chemical composition of an entire region from orbit.

This individual training meant I saw less of Jim and Dave as we began to concentrate more and more on the unique elements of our mission. The two of them spent a lot of time on Long Island working with the lunar module, as well as practicing the activities they would conduct on the lunar surface. Even when we trained together, I was often alone in the command module simulator, talking to them in the lunar module simulator. We were probably only in the same simulator for 20 percent of the training time. That made sense, as there were only a limited number of times, such as launch and reentry, when we would work as a trio. For maneuvers, midcourse corrections, and changing our orbit around the moon, it made more sense for me to train solo.

I felt that my work was just as important as the lunar surface exploration. The rocks collected on the surface would be the ground truth, an important part of the puzzle. Dave and Jim would collect samples, identify where they found them, and take photos to mark the locations. When we returned them to Houston, those rocks could be analyzed in greater detail. We could then compare them to the data I would collect of that whole area from orbit and work out a system where the two sets of data agreed with each other. Since I would be passing over other sites where moon landings had been and would be made, we could build up quite a database of comparison. With this combination of information, we could learn about other areas of the moon without ever needing to land there. Since Apollo wouldn’t land on the moon as many times as originally planned, this information would be vital to collect.

It wasn’t going to be easy. As engineers and technicians finalized their work preparing the first-ever SIM bay, they constantly ran into technical problems. Some of the equipment came out from the spacecraft on long booms, and this was tough to replicate in Earth’s gravity. When the instruments were turned on, the data did not always flow well. The engineers made a lot of last-moment tweaks and adjustments. I was too busy training to be very involved and just had to hope it would all be ready in time for our flight.