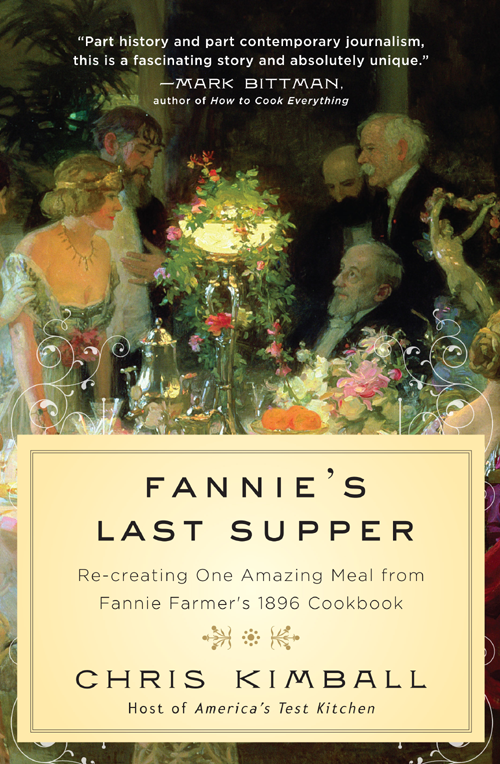

Fannie's Last Supper

Read Fannie's Last Supper Online

Authors: Christopher Kimball

Fannie’s

L

AST

S

UPPER

Re-creating One Amazing Meal from

Fannie Farmer’s 1896 Cookbook

Christopher Kimball

For Kate

Chapter 1

A Culinary Time Machine

A Seat at the Victorian Table

A

high Victorian dinner party was a modern re-creation of the ancient ritual of class and culinary artistry, displaying the plumage of high society while underlining the rigid rules of proper social intercourse. It was tails for the gentlemen and full dress costume for the ladies. One was expected to arrive neither early nor more than fifteen minutes late. When dinner was announced, the guests were led in procession from parlor to dining room, the host escorting the honored lady of the evening. The standard twelve courses were to be served briskly, in no more than two hours, yet there were few restraints on the amount of silverware used, with up to 131 separate pieces per setting in myriad styles from neoclassical, Persian, and Elizabethan to Jacobean, Japanese, Etruscan, and even Moorish. The rules of behavior were well known to all diners: one was never to appear greedy, draining the last drop from a wineglass or scraping the final morsel from the plate; one never ate hurriedly, which implied uncontrolled hunger; and since meal preparation was not something to be shown in public, plates were prepared out of view.

Within this rigid construct, food was the creative spark, the manna for imagination, and the kitchen a place where one was at last allowed to express one’s wildest desires. Victorian jellies with ribbons of colors and flavors, Bavarian cream fillings, and hundreds of custom molds were a culinary free-for-all, as was the sheer variety of a twelve-course menu, from oysters and champagne to fish, turtle, goose, venison, duck, chicken, beef, vegetables, salads, cakes, bonbons, coffee, and liqueurs, all carefully orchestrated from soup to crackers to provide an eclectic, wide-ranging array of tastes and textures. Among the very wealthy, these dinners occasionally crossed the line from artistic perfection to excess, with menus that included roasted lion, naked cherubs leaping out from live-nightingale pies, chimps in tuxedos feted as guests of honor, and gentlemen in black tie dining on horseback. The Victorian dinner table was a moment in time that encapsulated the dreams of a young country—the radical pace of change from farm to city, from water to steam power, from local to international, from poor to rich—that defined our nineteenth century, and this food, these menus, this dining experience have today remained dormant for over a century, just waiting to be rediscovered: the old cast-iron stove lit once again, the venison roasted, the geese plucked, and the dining table decorated using the furthest reaches of culinary imagination.

And so, in 2007, with Fannie Farmer’s original 1896 Boston Cooking School cookbook in hand, using a twelve-course menu printed in the back of the book and an authentic Victorian coal cookstove installed in our 1859 Boston townhouse, I set out on a two-year journey: to test, update, and master the cooking of Fannie Farmer’s America, re-creating a high Victorian feast that I hoped to serve in perfect succession to a dozen celebrity guests for a televised public television special.

The project had begun with a book. It was horse chestnut brown, the color of a dark penny roux, mottled through a century of use, and measuring just 5 by 7¾ inches. The cover had separated from the binding, and there was no printing on the front or back—just a simple mustard yellow title on the upper spine:

Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book

. It was subtitled, on the inside,

What to Do and What Not to Do in Cooking.

The book was published in Boston by Roberts Brothers in 1890, seven years after the first edition; it was 536 pages. In 1896, Fannie Farmer, the new head of the Boston Cooking School, revised, updated, and expanded Mrs. Lincoln’s work.

I had found it in 1983 through an act of pure serendipity, in the library of a house I was thinking of purchasing at the top of Mine Hill Road in Fairfield, Connecticut. It was a two-story white clapboard number, more a square than a colonial rectangle, well proportioned and big enough for a small family, but no trophy house by any stretch. The former occupant, well in her eighties, had just died; she had been the German mistress of a long-departed lawyer in town who had willed her the use of the house during her lifetime. Coming up the back steps into the kitchen for our first inspection, my wife-to-be, Adrienne, and I noticed the antique gas stove, the even older four-door General Motors refrigerator, and a screen door between the kitchen and the dining room, as if the occupant had kept live chickens or goats secluded from the rest of the living quarters.

As the Realtor took Adrienne on a tour of the upstairs, I sat on a window seat and read the preface of the small cookbook I’d found abandoned on a shelf. In it, Mrs. Lincoln put forth her premise: to compile a book “which shall also embody enough of physiology, and of the chemistry and philosophy of food.” Hmm, that sounded quite modern to me, hardly what I might have expected from a book published in 1890. She went on to define cooking as “the art of preparing food for the nourishment of the human body. [Cooking] must be based upon scientific principles of hygiene and what the French call the minor moralities of the household. The degree of civilization is often measured by its cuisine.” Clearly, she was a heck of a lot more enlightened regarding cooking and diet than 99 percent of all cookbook authors today, most of whom were promising meals in minutes.

Who were these Victorian cooks? Years later, while researching this book, I came across an awe-inspiring account of the Boston Food Fair of 1896. This made the contemporary Fancy Food Show look like amateur hour. A series of over-the-top meals was served, including a “Mermaid’s Dinner.” There was an electric dairy in the convention hall that churned out three thousand pounds of butter each day, a towering replica of a castle to promote flour, and a giant barn with grass, trees, and a Paul Bunyan–sized cow whose only purpose was to promote canned evaporated cream. Women queued up for free samples from two hundred different vendors: shredded wheat, cereals, gelatins, extracts, ice cream, candy, and custards. Other booths promoted shredded fish, preserved fruits, olives, baking powders, and dried meats. And then, just to remind us that we were still in the Victorian age, tucked darkly under the stairs, was the perfect dour touch: a melancholy exhibit of gravestones to remind passersby of their inevitable end. Just as today, food and cooking were at the convergence of popular entertainment and capitalism.

In fact, in the late 1800s, the culinary world was on fire, as technology came to the rescue of the exhausted home cook with modern versions of classic ingredients. Powdered gelatin had recently replaced ungainly thickeners such as isinglass, made from the swim bladders of sturgeon, or Irish moss, made from seaweed, or, God forbid, calf’s-foot jelly, a smelly proposition indeed. Jell-O was even marketing an ice-cream powder in vanilla, strawberry, chocolate, and lemon as an alternative to making the real thing. Gas stoves were coming into use, replacing dirty, high-maintenance coal cookstoves. Fruits were being shipped in from California and the Northwest, mushrooms from France, extra-virgin olive oil from Italy, and cheese from all over Europe, including real Parmesan and Emmanthaler. Sugar was now modern and highly refined, no longer consumed in yellow loaves, but pure white and granulated. Contemporary cookbooks, especially

The Epicurean

by Charles Ranhofer, exhibited an advanced knowledge of cooking and the assumption that home cooks were up to the task of creating elaborate masterpieces.

Then a strange and self-indulgent notion struck me. Trying to understand the culinary past through old cookbooks and newspapers is a dodgy enterprise at best. A century or two from now, would historians be able to paint an accurate picture of home cooking in the early twenty-first century by reading the

New York Times

food pages or looking at Amazon best-sellers in the Cooking, Food, and Wine category? Instead, why not just cook my way back through history—investigate the ingredients and the techniques; make the puddings, the soups, the roasts, the jellies, and the cakes; and then give myself a final exam, a twelve-course Victorian blowout dinner party that I would serve to the most interesting group of guests I could cobble together? Oh, and I should do all of this on an authentic coal cookstove from the period and make everything from scratch, including the stocks, the puff pastry, the gelatin, and the food colorings. It would be like building a culinary time machine: I could travel back through history and stand next to Fannie as she cooked, feeling the intense heat of the cast-iron stove and the chill of the thin strips of salt pork as I larded a saddle of venison, and then follow her instructions precisely as I handled a poached calf’s brain so gently that it did not dissolve into custard.

This idea was to remain nothing more than a daydream until 1991, when I moved to Boston and purchased an 1859 brick bowfront only a few blocks away from Fannie Farmer’s home in 1896, the year that she published

The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book

. I still had to renovate the house and re-create an authentic Victorian kitchen—all of that would take years—but the seed had been planted. My fantasy dinner party, sleuthing the Victorian age through its recipes, was about to be born.

In Which We Move to the Wrong Side of the Tracks

T

he house or, more explicitly, the 1859 brick Victorian bowfront, was located in a neighborhood referred to as St. Elsewhere of TV show fame, just one block from Boston City Hospital and on the wrong side of the tracks. The elevated trolley that ran down the center of Washington Street was demolished in 1987, and, sadly, the social demarcation still existed. The neighborhoods east of Washington Street (and therefore farther away from Back Bay and the central shopping district) were still considered to be a no-man’s-land in terms of real estate value and personal safety, even though the physical dividing line, the one that had separated our neighborhood from the rest of the South End, was now gone. In fact, the entire South End, the term for the 526 acres of Victorian housing that was the flip side of Back Bay, was a complete train wreck in 1991, suffering from a statewide depression and collapse in real estate values. Thousands of adventurous baby boomers had invested in South End property, only to see their condominiums plummet in value, making them hostage to an area of Boston that now looked down and dirty instead of up and coming.

How bad was it? It was such a tough neighborhood that in April 1991, my wife, Adrienne, spent a whole morning parked outside the building to check out the foot traffic before we committed to the purchase. It was not encouraging. She noted, among other details, that drug dealers hid their stash underneath loose sidewalk bricks so they would be clean if searched. Another aspect of South End living was revealed by a long-time resident across the park, who told us of the day she returned home with her groceries. She found her back door blocked by a working girl pursuing the world’s oldest profession with a local customer. She asked them politely to move over so that she could get into her house; they grudgingly complied. A few years later, we were told about a resident of West Newton Street who decided to move when he came out one morning to find blood all over his Toyota—a man had been stabbed on the hood during the night. This same street had, for many years, boasted of a mobile car repair service; the mechanic worked on your car where it was parked, scavenging spare parts from other cars around the neighborhood.

My immediate impetus for the move was a call in January 1991 from an old friend who had recently purchased

East West Journal

and was looking for a partner to come to Boston and transform the publication from a money-loser to a money-maker, a process that took two years and a name change to

Natural Health.

Meanwhile, I was learning a bit more about the South End. The good news was that hundreds of buildings had been untouched since the Victorian era—that is, the owners had lacked sufficient funds to modernize or otherwise destroy the original interior structure, and the exteriors were protected by law. Most of the South End was built in the late 1850s and 1860s, the larger homes being close to Washington Street, the main thoroughfare into Boston in the old days, with five full stories plus a basement. Smaller homes with a narrower footprint were built closer to the center of town and Back Bay.

After showing us a series of smaller homes in better neighborhoods, our Realtor finally, and somewhat reluctantly, drove us down to a square adjoining Boston City Hospital. At the time, this was the worst part of the South End, and so close to Roxbury that the post office, to this day, labels our mail as “Roxbury,” rather than “Boston.” As we turned into the square from depressed and hard-luck Washington Street, the first thing we noticed were the gutters layered with compressed trash and the narrow park in the middle of the square that was windswept with coffee cups, loose papers, the odd used condom, and the contents of garbage bags that had been eviscerated by razor-wielding homeless seeking deposit bounty. Putting aside the forlorn and abandoned look of the square, which was in reality a long, narrow oval, the good news was that a new fountain had just been installed and the park was dotted with massive Dutch elms, some of them reaching almost as high as the five-story Victorian townhouses that ringed the park. It was easy to see former glory here, although a wasting disease had clearly set in decades before and the patient was on its last legs.

But then, all of a sudden, we were standing in front of our home-to-be, and it was love at first sight. It was a classic Boston redbrick Victorian: a bowed front taking up two-thirds of the width of the house and then a flat face for the rest, with two dormer windows on the top floor built into an angled slate roof. A steep procession of steps led up to the main entrance on the second floor, with a small arched-top entrance tucked under the stoop.

Adrienne and I climbed the length of steps and then passed through two sets of double doors into the second-floor parlor level. We had, in just a few steps, traveled back a hundred years. The foyer was small, the house dark and quiet, the air stale as if the windows hadn’t been opened in years. To the right were the stairs with a curving mahogany wood banister; light filtered down softly from the fifth floor through a skylight positioned over the stairwell. There was a short hall straight ahead, and to the left were a pair of magnificent dark walnut doors that opened into the front parlor. This room featured twelve-foot-high ceilings, curved front windows overlooking the park, and a fireplace with marble mantels and carved surrounds. Two pocket doors with etched glass panes led into the dining room, which had its own fireplace and double windows. The plaster ceiling moldings were elaborate with medallions and cornices. Chair rails ran around the walls. The only detail that required immediate attention was the raspberry eggshell paint—a color that must have been chosen by someone who was blind drunk during a blackout.

We climbed one set of stairs to the third floor, where we discovered a library, also facing the park, with a working fireplace, high ceilings, and Corinthian columns on either side of the doors. As we kept moving up, we saw that the two top floors had the same basic floor plan: a large room in the front with a small dressing room or bedroom off to the side and a slightly smaller bedroom in the back of the house with an adjoining bathroom. The top floor had dormer windows, and the basement still contained two original soapstone sinks for doing the wash, plus an intact coal bin enclosed by massive stone blocks. There was two-car parking out back, and since none of the former owners had much money, the house was more or less intact, with the exception of locks cut into doors and the first and top floors having been walled off as rental units. Over the years, as we removed the two apartments and restored the house to its original plan, we had a total of five bathrooms, six bedrooms, a library, an office, a large playroom on the fifth floor, a full basement, a large living room, a good-size dining room, a butler’s pantry, working sinks in two of the bedrooms, and plenty of closets—all for the price of a one-bedroom condo on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

Clearly, this was the perfect home to raise four kids. The five-story layout provided plenty of privacy, but there was one problem: we felt like prisoners in our own home. The neighborhood offered the constant scent of personal danger: screams in the middle of the night; gangs of young kids constantly moving through; prostitutes, drug dealers, and the sense that nobody who could afford to live somewhere else would be here.

The first six months was like a first-time tour with the Peace Corps—we had a severe case of culture shock. We served on the board of the local neighborhood organization, where, on one memorable evening, I almost got into a fistfight with a neighbor who told me that if we did not like heroin needles sticking out of the fences around our parking area, we should never have moved to the South End in the first place. Hey, the drug addicts were here first! We threatened local drug dealers with exposure, hung out with off-duty detectives who gave us the lowdown on recent crimes, got tricked by numerous kids who knocked on the door and asked for contributions to various totally fictitious school projects, and watched prostitutes climb up fire escapes in the alley to an abandoned fifth-floor rental unit, which they were using as their “office.” We participated in the annual spring cleanup run by longtime local and ward chief Steve Green, who smoked cheap cigars and drove his pride and joy, a Subaru station wagon with two hundred thousand miles on it. Adrienne and the kids attended one of the first legalized gay weddings in the state. And on a more memorable occasion, Adrienne and our son Charlie were held up at gunpoint by a drug addict. Adrienne told him off, grabbed our son, and then threw a few twenties at him, telling him to get lost. That’s what city living does to you.

We also began our education about all things Victorian by joining the South End Historical Society, housed in a private building just off of Massachusetts Avenue on Chester Square, a few blocks from our house. We learned that the Victorians, including Fannie Farmer, made a distinction between private and public spaces within a house. (This is in stark contrast to current homeowners, who will give you a tour of their entire house, including the bedroom, at the drop of a hat.) The second floor, with its large front and back parlors plus a small music room off the back, was for entertaining. This is why the ceilings were high and the architectural finish was so elaborate. Downstairs, the family dining room was in the front of the house and the kitchen was in the back. The third floor front, what we ended up calling the library, was also a public space, given its detailed ceiling and door moldings—a place where the woman of the house might entertain a friend or two. However, the rest of the house was private. If there was live-in domestic help, they were housed on the top floor, the hottest space in the summer. Victorians were also less apt to invite friends over for dinner. Dining in someone else’s home was an intensely personal event, and an invitation was the “highest form of social compliment.”

These 4,500-square-foot homes were heated with coal furnaces that ran hot air up the flues and out into the room through vents in cast-iron fireplace inserts. These were not wood-burning fireplaces as originally conceived, although some houses did offer coal grates in the large second-floor parlors. Heavy drapes were one hallmark of the Victorian era; they were highly functional, keeping out cold air in the winter. In summer months, drapes were removed and cleaned, leaving simple lace curtains that allowed for the flow of fresh air. The kitchen was always on the ground floor in the back of the house; our original brick hearth was still intact. Cooking would have been done on a small coal cookstove with two ovens located above the cooking surface on either side of the flue.

About 1860, the South End had begun life as a rich man’s alternative to Beacon Hill. A few wealthy residents had even built mansions that took up an entire city block, complete with stables and circular driveways. But most dwellings did not last as true single-family homes for long. By the time Fannie Farmer had moved into the South End in the 1890s, the neighborhood was already well on its way down the slope toward urban decay, since Back Bay, which was built in the 1880s, was now the more desirable location. The rich moved out, real estate values dropped, and by the 1960s, many buildings could be had for as little as $10,000. The Pulitzer Prize–winning book

Common Ground

detailed the struggle of young families in the South End in the 1970s during the busing crisis, trying to start their own schools, chasing drug dealers down the street with baseball bats—the sort of thing that was not uncommon deeper in the South End in 1991, the year that Adrienne and I moved in. Although the portion of the neighborhood closer to Back Bay had now become gentrified, our home in St. Elsewhere was still at the very beginnings of a turnaround. It was a hodgepodge of mixed-income apartment houses, Victorian townhouses, a large gay population, and a vibrant ethnic mix. That was, in our opinion, its charm, although the area was so poor that it could not sustain a half-decent restaurant, drugstore, bakery, coffee shop, bookstore, or supermarket. It was like living on runway 3 out at Logan Airport—you were a long way from anywhere familiar.

But by the late 1990s, we had settled in and come to love our slowly improving neighborhood, and my interest in Fannie Farmer had surfaced once again. I discovered that during her tenure at the Boston Cooking School Fannie Farmer had lived no more than twenty feet from my early-morning walk to the bus with my two girls, Whitney and Caroline, at 87 West Rutland Square. (The 1900 census shows that the house at 87 West Rutland Square was full. The entire Farmer family had settled in: Frank and Mary with their four daughters, Fannie, Mary, Cora, and Lillian, plus Cora’s husband, Herbert, and their son, Dexter. There was also one servant, Ellen Macadam, who was twenty-four years old, and two lodgers, both schoolteachers: Harriet Bolman and Fanny Batchelder. By 1910, the extended family had moved to Huntington Avenue, just a few blocks away. Both of Fannie’s parents were still alive at the time of the 1910 census.)

Living in a house constructed in 1859 does one of two things: Either it makes you hungry for modernity, so you rip out most of the interior and install glass floors, two-story ceilings with skylights, and a thoroughly modern granite-counter kitchen. Or you fall in love with the past and become intensely curious about what life was like the year the house was built. Adrienne and I fell into the latter category. I started to ask basic questions: What kind of town was Boston in 1896? What was it like to step out the front door on a Monday morning and go to work? Whom would you see on the sidewalk? What about the stores, public transportation, and the other buildings? Was it an earnest backwater or a sophisticated, lively place to live and work?

For starters, Boston had 448,477 residents in 1896, including 8,590 “colored” and 158,172 foreign-born, half of whom were Irish, 5,000 of whom were Italian, and 20,000 of whom were Jewish. The Boston Social Register listed 8,000 families, of which a mere dozen were Catholic; only one person, Louis Brandeis, was Jewish. The

Boston Globe

of that era accused Lizzie Borden of killing her parents in Fall River on August 4, 1892; in the early 1890s, a great financial panic set in—the greatest since 1873—and the economy didn’t rebound for almost five years. In 1895, with city finances again on the upswing, the Boston Public Library opened in Copley Square at a cost of $2.5 million. Designed by McKim, Mead, and White, it contained paintings by Sargent and Whistler.