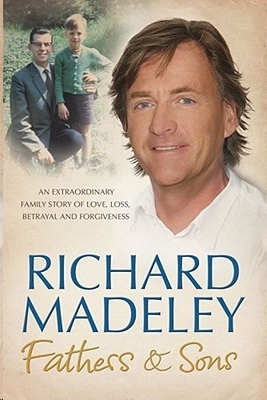

Fathers and Sons

Authors: Richard Madeley

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright © 2008 by Richard Madeley

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Richard Madeley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray’s Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-10: 1-84737-493-X

ISBN-13: 978-1-84737-493-6

To my adored wife Judy, for her unfailing encouragement

during the writing of this book, and to my beloved daughter

Chloe, for not minding that I didn’t write about fathers and

daughters.

Not this time, anyway.

We are the children of many sires,

And every drop of blood in us

In its turn…betrays its ancestor.

–

Ralph Waldo Emerson

I

was twenty-one when my father died, suddenly and with no warning to anyone but himself; a few twinges in his chest which he put down to a hurried breakfast or strained muscles from a weekend spent vigorously forking the rose beds.

His last morning on earth was spent prosaically at the office. By lunchtime the symptoms of coronary thrombosis must have been unmistakable, because Dad did what many men are strangely compelled to do when their hearts give notice of imminent convulsion–he headed for home. Perhaps men instinctively seek the privacy and sanctuary of their cave when catastrophe beckons; at any rate, my father managed to drive himself to his front door, fumbled desperately with the key, staggered inside and collapsed into my appalled mother’s arms.

He had three minutes to live.

Dad said that his arms and hands were tingling and he felt very cold. Mum settled him on a sofa, called an ambulance and rushed upstairs for blankets. When she got back

to him, he was now struggling to breathe but, ever the journalist–a career he’d begun thirty years before–managed to gasp: ‘My expenses from last week…they’re in the glove box.’

My mother urged him to lie still and wrapped her arms around him. This was to prompt my father’s last words. As is often the case with final words, my father’s proved to be disappointingly mundane. No last pearl of wisdom; no sweeping but pithy summary of forty-nine years of existence. ‘Do you have to lean on me so bloody hard?’ he gasped, before his life winked out with the sudden totality of a power cut. The light of my mother’s life had been snapped off with a querulous rebuke.

Like most sudden deaths, my father’s triggered multiple impacts. My mother, still a relatively young woman in her early forties, now faced the prospect of completely rebuilding her life. My sister and I had to face up to the prospect of a future without a father’s guidance and love. Even in the depths of our grief I think we all knew, deep down, that we would adjust, absorb the shattering blow, and adapt. But for one member of the family, this would be quite impossible. For this person, the death of Christopher Madeley on the afternoon of 8 August 1977 would shroud what remained of his own life in speechless sorrow. That person was my grandfather. Geoffrey Madeley, my father’s father, never recovered from the loss of his youngest son–a son he never once told he loved.

Geoffrey, Christopher, Richard and Jack. Fathers and sons, four generations strung together like beads on the twisting double helix of their shared DNA. Utterly unalike when regarded from some angles; almost clone-like in their similarity when viewed from others. Climbers roped together through space and time, mostly barely conscious of distant twitches on the line, but sometimes pulled up sharp by a sudden unmistakable tug from the past.

The story you are about to read spans a century, from 1907 to the present day; a hundred years of unprecedented change and transformation during which British society convulsed as never before. With these paroxysms, the roles of men and women within the family were fundamentally altered. Fatherhood evolved into something very different from the models of the past.

Men now face major challenges to their traditional position in the home. The lines between motherhood and fatherhood have become blurred, and that burgeoning new science of our era–psychology–has ushered in a new age of self-awareness and analysis. Today’s fathers must surely have more insight into their roles as parents than previous generations, and yet they are probably just as confused as their forefathers were.

So begins our expedition; a survey of the lives of Madeley men that may chart a map of sorts for other fathers and sons. It is a long way back, and some of the details passed down from events that took place over a century ago have been blurred not only by time but by subtly differing family accounts. I have tried to reconcile these here.

But be in no doubt: these are true stories.

We start with my grandfather, and a tale of childhood abandonment and cold-hearted exploitation that could have come straight from the pages of Dickens.

KILN FARM

M

y grandfather awoke on a feather bed in a bare room that smelled of apples. His ten-year-old mind struggled to remember where he was and why he felt a growing sense of excitement. Then consciousness returned; he was in the orchard room of his uncle’s and aunt’s farmhouse. He, his parents and his six brothers and sisters–all of them, from baby Cyril to big brother Douglas–were halfway to Liverpool. They’d said goodbye to their old home in Worcester the day before and packed their belongings on to a horse-drawn cart. This was a place called Shawbury. Mother and Father had told them they had one more day’s journey before they would see the great ship that was to carry them all across the sea. Father said they should be prepared for storms and enormous waves.

My grandfather turned to discuss this thrilling prospect with the brother he had shared the bed with, but the other was up and gone. As Granddad hurriedly dressed, he wondered

why the house was so still and quiet. Everyone should be up and preparing to leave by now. They’d meant to set off at dawn, but the sunlight slanting through the window on to the brass bedstead told him that morning had broken hours ago. Why hadn’t anyone thought to wake him? Surely they couldn’t have forgotten him!

Not quite. As the small boy trotted and then ran from room to room, each as silent and empty as the last, the children and parents whose names he called out in increasing desperation and panic were already long gone on the road to Liverpool. My grandfather had not been forgotten.

A deal had been done.

He was left behind.

The whole thing was Bulford’s fault. Bulford didn’t mean anything by it; he didn’t set out to bring down a catastrophe on my grandfather’s head, a stunning blow that would judder and ripple down through generations of Madeleys to come. Bulford was simply taking care of business; in this particular case,

his

business.

‘Mr Bulford, from Birmingham.’ That’s how this turn-of-the-century businessman was always referred to by my grandfather’s side of the family. Bulford was the moneyman in a partnership with my great-grandfather Henry George Madeley. Henry was a farmer’s son from Shropshire but had no intention of working on the land. As soon as he could he left the farm in the care of his two bachelor brothers and

spinster sister and set up shop, literally, down in Worcester. With Bulford’s backing he opened a grocery shop in the city’s Mealcheapen Street. Business was brisk enough for Henry to marry, sire seven children, and live comfortably with his wife Hannah at the family home half a mile away, in Stanley Road. By 1907 their progeny ranged from baby Cyril to fifteen-year-old Douglas, with my grandfather, Geoffrey, coming in at number three. Geoffrey was ten. He didn’t know it, but Bulford from Birmingham was about to terminate their happy hearth and home with casual abruptness.

Bulford called Henry to a meeting. He was sorry to inform him that he had decided to retire from business, and would therefore be removing all his capital from their joint venture forthwith. He was sure Henry would do very well by himself.

Henry was stunned. He tried his best to find a new backer but there were no takers. He couldn’t go it alone; his partner’s sudden exit meant the end of the little shop on Mealcheapen Street and, it seemed, the Madeleys’ comfortable life in genteel Worcester. Henry had seven mouths to feed–plus himself and Hannah. Cyril had arrived only months before Bulford dropped his bombshell. Henry had to come up with something, fast, or his family would be out on the street.

There was always the farm…

Henry’s brothers William and Thomas were still up in Shropshire with their sister, Sarah. She looked after the two men while they worked the tenancy on Kiln Farm. With its tiny herd of a few dairy cattle it wasn’t exactly a goldmine, but maybe something could be worked out.

Kiln Farm stands close to the village of Shawbury, about

seven miles outside Shrewsbury. A century ago, it was a remote place to live. A few miles to the south rose the dark, barrow-shaped hump of a prehistoric volcano, the Wrekin. Standing like teeth along the western horizon lay the Stretton Hills, and behind them, Wales. Kiln Farm nestled in the shallow, almost saucer-like depression of the Shropshire Plain, Roman-hot in summer, arctic-cold in winter. Few places in England are as far from the sea and the region has the closest thing this country knows to a Continental climate.

Henry had absolutely no intention of returning to live there, and still less of going back to work on the land. He’d been gone much too long for that and, anyway, his brothers were unlikely to welcome an extra tenant farmer sharing their meagre profits. Besides, where would they all live? A rented tumbledown cottage out in the sticks was unthinkable after the comforts of Stanley Road.

But Henry began to think his brothers might be willing to help him in other ways. There was nothing to keep him and his family in Worcester. Come to think of it, there was nothing to keep them in England at all. Henry knew people who had emigrated to Canada and by all accounts were getting along very well there, thank you. Why shouldn’t the Madeleys do the same?

For one insurmountable reason. He had no money to buy transatlantic tickets, and no money to get his family established once they had arrived. But surely a loan of some sort could be arranged? William was his brother, after all.

Henry went back to Kiln Farm. Alone. He had no collateral to offer, he explained to William, other than his word. William

told him collateral would, unfortunately, be required, but not to worry.

He had a proposal of his own to make…

The farm, so strangely quiet this sunny morning, had been full of happy noise the night before. Of course, the little ones didn’t really know what was going on. Cyril was still a baby and not even talking yet. Katherine, who was three, Doris, eight, and William, five, seemed to think they were off on holiday somewhere and Geoffrey could understand why–it

did

feel as if they were off on holiday, only, well, somehow much

bigger

than that. He and his two older brothers, Douglas and thirteen-year-old John, knew exactly what was happening. They were all about to emigrate. Leave for Canada, and never come back, not like you had to from a holiday.

Geoffrey went to sleep dreaming of silver dollars and snow.

A few hours later, running in increasing panic through the empty bedrooms, he realised something else in this unfolding nightmare was all wrong. Everyone’s bags had gone. Everyone’s but his. He rushed down the stairs to find his aunt and uncles sitting by the kitchen fire. They looked uncertainly at each other. Then Uncle William said they had something to tell him.

Quite who explained to my grandfather why his family had secretly abandoned him is a question with tantalisingly

different answers. One family version has it that Henry took his family to Liverpool via Shrewsbury, and then delivered Geoffrey in a detour to Shawbury. If so, was the little boy informed of his fate during the short journey, or on arrival? He had holidayed at Kiln Farm the previous year–rather oddly, the only one of his brothers and sisters ever to do so–so perhaps he thought he was being taken there to say his goodbyes. This alternative account has a somewhat less emotive quality, but it seems to me even more cold-blooded than the first.

Both my parents always believed that my grandfather arrived at Kiln Farm with everyone else, and was left behind in a dawn–or perhaps even midnight–flit. I am certain he never got to say his farewells because when I was a teenager, on one of my long walks with the old man, I asked him, ‘Didn’t you even get a chance to say goodbye, Granddad?’ and with perfect composure he replied: ‘No. No, I didn’t.’

So what was Henry’s ‘arrangement’ with the eldest brother, William? No contract was ever discovered; it is probable the whole deal was done on a handshake. Some in my family know nothing of any arrangement; others–including my parents–were absolutely certain there was one, and say my grandfather spoke of it long years after.

It was certainly William who would have set the terms. And what terms! He would advance the money for one-way passages to Canada for everyone except Geoffrey. At ten years old, the boy was William’s natural choice to stay behind. He would soon be strong enough to help out on the farm, and young enough to give the maximum years of service before reaching his majority.

William threw in a couple of sweeteners. When Geoffrey was twenty-one, he would be ‘allowed’ to visit his family in Canada. This, eleven years after they had all sailed there without him! Of course, it was up to him whether he came back to England or not, but if he did, and assuming he was up to the job, he would be promoted to farm manager. If by then William had succeeded in his ambition to buy the farm, he would leave it to Geoffrey in his will. He had no children of his own, after all. That was the offer. Henry could take it or leave it.

Henry took it. At what stage he broke the terrible news to his wife–that she was to be parted from her third-born child, that her little Geoffrey was the price her husband had paid in exchange for a fresh start in Canada–we do not know. But we do know that Hannah was distraught. Years later her youngest child, Cyril, would visit my grandfather in England and describe to him their mother’s ‘awful grief’ at having to leave her beloved boy behind.

What wrenching, desperate exchanges husband and wife must have had in the privacy of their cabin.

They need hardly be imagined.

But still their ship pounded inexorably westwards to Quebec. Henry’s decision was irrevocable.

Hannah, even in her grief and anger, must have realised that. For what was to be done? Unthinkable to spend the stake money William had advanced them on return tickets to England, there to reclaim their abandoned son. How would they pay William back? How would they live?

Where would they live?

The die had been cast. Geoffrey’s fate was sealed from the moment his father and uncle shook hands on their deal at Kiln Farm a hundred years ago.

Some years before he died I asked my grandfather who had given the news to him. He maintained a wonderful silence for so long that I thought I had offended him. Then finally he said, so quietly that I could barely hear: ‘It was a very long time ago. They all thought they were doing their best.’ But he confided in my parents that it was his Uncle William who delivered the

coup de grâce

.

At the time, Granddad later revealed, the shock of being abandoned was total. He said the panic and fear were so intense as he grasped the depths of his betrayal and sacrifice, he could scarcely breathe. Ten years later he would experience the living nightmare of trench warfare in France, but even the grotesque horrors of shelling, gassing and hand-to-hand fighting–a smooth euphemism for the worst that men can do to each other face to face–were less dreadful to him than the crushing moment when he realised he had been deserted and delivered into a kind of serfdom.

Not that he meekly accepted his fate without a fight. That night, after a day spent speechless with shock, he was put to bed by candlelight. Geoffrey waited, motionless, for the household to fall asleep. As soon as he was certain, he slipped out of bed and dressed as quietly as he could. He had formed a plan; a plan so sickeningly bold it made him dizzy with apprehension. He would slip out of the house and follow the pitch-black lane to the village. He knew the way. Once there he would knock at the first house with lights still burning and

ask for directions to Liverpool. He’d start walking there straight away and, with luck, hitch a ride on a cart or wagon after daybreak. He could remember the name of the ship and he’d find it somehow and…well, his parents would have to take him with the others then, wouldn’t they?

It was a hopeless plan. It is almost fifty-five miles from Shawbury to Liverpool and he would quickly have become lost and been picked up by the police–but he was too little and too desperate to understand that.

Or to unpick the lock on the stout wooden door at the foot of the stairs which had been thoughtfully turned with a key. A key that was, of course, no longer there.

It is difficult for us today to fully appreciate just how isolated and rudimentary ordinary rural life was as recently as the early decades of the twentieth century.

My grandfather’s new home was a brick-built Victorian farmhouse set in fields sloping down to the River Roden, which rolled slowly towards the Severn a few miles downstream. Across the river lay the village, reached by an ancient stone bridge. There was a pub, the Fox and Hounds, which served local ale brewed in the sleepy town of Wem nearby; a village store, the church, and some cottages. That was it–a world away from the little boy’s suburban upbringing in bustling Worcester.

There was no electricity or gas supply, and no mains water. One of the first tasks assigned to my grandfather was to

‘pump up’ first thing each morning, vigorously working the long wooden handle of the well pump behind the farmhouse. Sometimes the water refused to rise and he would have to prime the pump with a bucket of water kept by from the previous day. Then the crystal-clear, icy-cold liquid would gush from the pump’s iron mouth to fill the waiting jugs and basins.

Communications were extremely poor. There was no car, no telephone and no radio. This was years before the BBC. Newspapers were more or less unavailable, unless someone walked or took a cart into Shrewsbury or Wem, and why would anyone want to do that? Labour on the farm was gruelling, with only rudimentary mechanisation; carthorses did the work of the tractors that lay many years in Kiln Farm’s future. Work filled each day and bedtime was decreed by the setting of the sun, with a candle to light you to bed.

Few visitors came to the farm. Geoffrey’s new guardians were unmarried and childless, so there were no playmates on hand for him there. Quite how my grandfather adjusted to the sudden disappearance of brothers and sisters from his daily home life, let alone his mother and father, I can only guess at. But today, more than a century after he was lodged like a puppy at kennels with three virtual strangers, it breaks my heart to think how lonely and betrayed he must have felt, knowing all the time that somewhere, unimaginable miles distant, his siblings were greeting each new day together, with their parents at their side. At times, he confessed much later, he thought he would never see any of them again.