February (12 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Lord

Everything was soaked. The gang of three was long gone. I’d made my way back out of the drain and was now walking along unnoticed in the rain—just another drenched pedestrian, sodden and dripping.

I called Boges from a public phone, and he quickly came to my rescue … again. I don’t know how, but he managed to fix my damaged mobile and torch, and he gave me some dry clothes and a waterproof bag to store things more safely.

After about ten minutes he had to go again. If only I could have followed him.

The alcove in the drain was saturated. Puddles sat where I’d been sleeping—clearly it had not escaped the stormwater level. I tried to sweep it out with my wet clothes, so I could rest up for a bit, but I knew I couldn’t stay much longer anyway and risk being trapped.

I settled down, trying to sleep. My body and mind were still churning over the gang I’d faced and the flooding storm. I hated fighting.

Back in Year 1 at school, one day, Boges and

I were about to have our lunch on the benches under the trees when two big kids—Kyle Stubbs and Noah Smith—approached us.

‘What’s that rubbish you’re eating, weirdo?’ Kyle said, pointing at Boges’s lunchbox.

‘Yeah, weirdo?’ echoed Noah.

Mrs Michalko had packed Boges fried potato dumplings. She’d put in extra because she knew I loved them, too.

Even at six, Boges was reasonable and logical. ‘It’s called

piroshki

, and you’re the weirdo, not me.’

Kyle kicked Boges’s lunchbox, sending the potato dumplings flying out everywhere.

They rolled and coated themselves in playground dust and grass.

‘What’d you do that for?’ asked Boges. ‘What am I supposed to have for lunch now?’

‘Oh, boohoo,’ mocked Noah.

I looked around for a teacher but there was no-one in sight.

Kyle kicked at some of the piroshki on the ground. ‘You can still eat this,’ he said, with an ugly grin.

With his grubby hands, he scooped up some of the dirty potato dumplings. ‘Come on, open your mouth!’

Noah grabbed Boges and tried to prise his

mouth open. Boges kicked and struggled, almost falling off the bench. I didn’t know what to do; I was so much smaller than these guys. But when I saw Kyle trying to squash the dirt-encrusted piroshki into Boges’s mouth, something like fire raced through my body. With all my strength, I flew off the bench where I’d been sitting, and rammed Kyle Stubbs. I was only small, and Kyle was huge, but he went flying, knocking Noah in the process to the ground with him.

‘Come on Boges!’ I yelled, swinging round and yanking my friend up.

As Kyle and Noah tried to get back to their feet, we raced past them, kicking dirt into their faces.

They never bothered us again.

‘Can I please speak to Eric Blair?’ I asked. I’d finally decided to call Dad’s work to find out if Eric knew anything.

‘I’m sorry,’ replied the woman on the other end of the line, ‘Eric Blair’s on sick leave. He’s … he’s not well. I can take a message for you, but I’m afraid I’m not sure when he’ll be returning to the office.’

‘That’s OK, I’ll call back another time,’ I said, hanging up.

Straight away my phone rang, taking me by surprise.

‘Hello?’

‘Why haven’t you called me?’

‘Winter?’

‘Who else would it be? What’s the deal? Why the silence?’

‘What? I’ve been trying to call you—I tried you

heaps. Your mobile’s been switched off for two weeks!’ I started thinking how desperate I must have sounded and started to tone it down. ‘Whatever.’

‘Sometimes I’m hard to catch. There are things I have to do. Now, do you want to see that angel or not?’

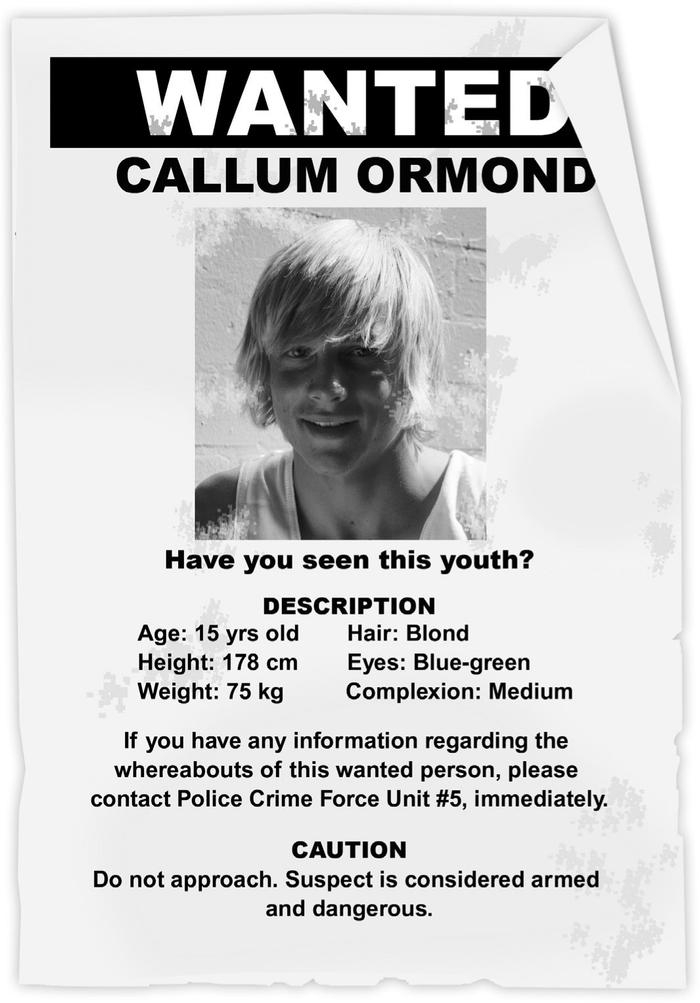

As I waited for Winter near the Swann Street station entrance, I looked over a community noticeboard at ads for part-time work, roommates, sales of laptops, cars and furniture. I moved further into the shadows when I saw some ‘no psycho’ tags next to a curling wanted poster with the face I once used to have on it.

Everyone seemed to want a piece of me.

I patted my backpack, checking to make sure the drawings were safe. I’d slipped the folder underneath the plastic backing of my bag, and unless someone did a really serious search, the drawings couldn’t be seen.

I spotted Winter before she saw me. In her drifty clothes, with the light of traffic headlights behind

her, she seemed like some strange being from a spirit world. As she walked closer I could hear the faint chiming of tiny silver bells that lined the bottom of her long, white skirt.

To my surprise, she kept on walking past me.

‘You wanna see the Angel, don’t you?’ she said, turning back, raising one eyebrow.

I looked into her dark, almond-shaped eyes and she gave me one of her cool smiles.

‘I could have waited until tomorrow,’ I said, ‘but you insisted it had to be tonight.’

‘That’s right. I’m busy tomorrow.’

‘School?’ I asked.

She shook her head. ‘I don’t go to school. I’m home-schooled. But it still had to be tonight. There’s a full moon. I need that.’

‘Are you planning on turning into a werewolf?’ I joked.

‘You’ll see. Well, come on then!’

Although I was joking about the werewolf thing, I realised as I followed her that I had no idea what she was up to. Boges’s words of warning were all I could think of. Good cop, bad cop.

I hurried along to keep up with her as she led me through the city streets, her wild hair trailing behind her. She walked like someone in charge of the world.

It wasn’t until we came to the bottom of a hill that I recognised the lane leading off to Memorial Park. The park I was abducted from.

‘Where are we going?’ I asked.

‘You’ll see.’

‘I’m the sort of guy who likes to know where he’s going.’

‘Are you now?’ She paused. ‘I thought you wanted to see the Angel.’

‘I do. I just wanna know where he is already.’

‘Look, we’ll get there quicker if you quit the questions.’

Last time I was here I ended up in a car boot, and then locked in a closet. I hung back.

‘Come

on

!’ Winter grabbed my arm. ‘You’re not afraid, are you?’

‘Of course not,’ I lied.

‘Then come on. We’re nearly there.’

She hurried along in the moonlight, silver bells ringing on her skirt. I tried to stay cool, but alert.

I kept looking around me, checking out every movement in the shadows. In this dark and secluded place, anyone could ambush us—or

me

. My heart jumped at the thought and a sickening

feeling in the pit of my stomach made it hard to concentrate. I was braced, ready for anything. To run like hell or fight for my life.

We stopped at the low, wide steps at the front of the cenotaph. I’d never been this far into the park before.

‘Sometimes the homeless sleep in here,’ Winter said, dragging open the rusted iron gates that had once closed off the central area of the memorial. The lock looked like it had long since fallen away.