February (13 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Lord

Just before going in she turned and held out the watch on her wrist. ‘See?’ she joked. ‘It’s almost midnight, there’s a full moon and I haven’t turned into a werewolf.’ She laughed and bared her teeth. ‘Not yet, anyway.’

We stepped over scattered rubbish and leaves and I tried to relax as she took my hand and led me further into the moonlit interior.

I found myself in the middle of a wide, circular space with an ornate mosaic floor. Ahead of me a figure stood on a tall stone pedestal—the sort of statue you see on graves or memorials. It was almost like being back at Crookwood Cemetery, when Boges and I were looking for the Ormond mausoleum at midnight.

It had been a warm summer night, but now a cold wind had blown in, lifting the dead leaves, making them skitter in an eerie little whirl. I shivered then looked up at the ghostly statue.

‘That’s not an angel, it’s just a soldier!’ Fear gripped me tighter. I was trapped. I’d followed her willingly into this creepy joint and now anyone could grab me, or the drawings.

I was about to hurry back down the steps when she called out to me.

‘Where are you going? Look up!’

She held out her arms and looked to the sky. ‘There’s your Angel!’

I hesitated a moment, then did as she said. I lifted my eyes until I was looking right over the statue’s head and at the stained glass windows high up the wall of the cenotaph. I gasped. There, lit by the light of the moon shining through the coloured glass, glowed the huge figure of the Angel

exactly as my father had drawn him

! His gas mask slung around his neck and tin helmet on his head. Behind him were his outspread wings.

I was stunned. I had found the Angel.

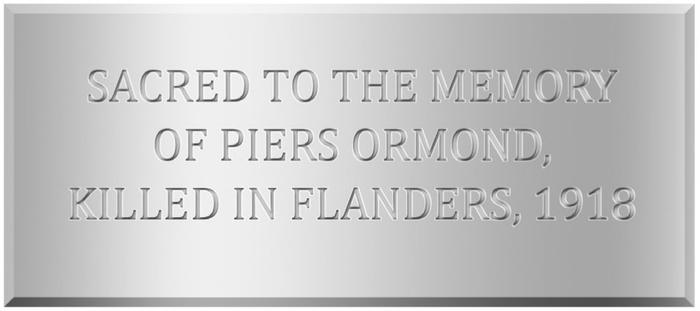

I don’t know how long I stared at him. It wasn’t until I lowered my gaze and found an inscription at the bottom of the figure that I realised why Dad had drawn this Angel twice—first in his letter to me from Ireland, and again from the hospital bed.

‘Ormond.’ I finally spoke. ‘That’s my surname.’ I turned to the girl beside me.

‘I know that. And yet you didn’t know about this memorial?’

‘I had no idea,’ I said, pointing to the stained glass window. ‘Dad told me ages ago that a relative had died in the Great War but that didn’t really mean anything much to me. I think he must’ve found something out about it when he was in Ireland and–’ I stopped myself in my tracks; realising I’d been on the verge of telling her about Dad’s last letter from Ireland where he’d begun explaining the massive discovery he was in the process of uncovering.

‘And?’

She frowned, realising I’d stopped myself for a reason. ‘It’s not a very common name,’ she said. ‘He could be a relative of yours.’

What did it mean? Why had Dad drawn Piers Ormond? How did Winter know about it? My excitement quickly changed to suspicion. ‘So how do you know about this Angel? Where did you find out about him? Did Sligo tell you?’

‘Sligo?’ Winter repeated. ‘Why would you think that?

He

doesn’t know about this.

He’s

never been here.’ She gestured towards the Angel. ‘This is where I come to get

away

from people like Sligo. Stop worrying, Cal. Your angel secret is safe with me.’

‘What do you mean,

secret

? Why are you saying that? Why do you think there’s some secret connected to the Angel?’

In the moonlight I saw her roll her eyes.

‘Oh man. Does being dumb come easy to you or do you really have to work at it? Of course there’s a secret about the Angel! Why else would you be so desperate to find out more? Why else would you be carrying drawings of this very Angel around with you? Why would Sligo be chasing something called the

Ormond

Singularity? Of course there’s a secret! You must think

I’m

stupid! Is that it?!’

She was right. It wouldn’t have taken a genius to figure that out.

‘I think you’re a lot of things,’ I said, finally, thinking that she was beautiful, strange, secretive, mysterious … and downright irritating, ‘but

stupid

isn’t one of them.’

She flashed a look at me. Now

she

was wary, unsure whether my answer was meant as a compliment or an insult. After a pause she spoke again. ‘I’ve known about this angel almost as long as I can remember. I used to come here

when I was little. When we were living in Dolphin Point. And then after the accident I came back here a lot.’

‘The accident,’ I asked, ‘when you lost your parents?’

She didn’t answer me. I knew she’d lost them in an accident, but what happened? I knew it was probably still far too soon for her to reveal that to me, if ever. She turned away to look up at the Angel again. ‘Yeah, I used to come here all the time. This was my special spot. It’s cool in here in the hot weather, and during the day it’s mostly deserted. I still like to sit here sometimes, especially when I’m sad.’

If I hadn’t seen the sadness on her face when she showed me the photographs of her parents in her locket, I would have said that Winter Frey was way too cool for sad.

Too cool and too tough.

I started to feel that just maybe I could trust her. Was she telling the truth? I had no way of knowing. I put Boges’s warnings to the back of my mind and tried to enjoy the moment. This Angel finally connected the Ormond name with two of my dad’s drawings, and to the Ormond Riddle. This stained glass window with its information about Piers Ormond was a huge piece of the puzzle Boges and I were trying to put

together. I whipped out my mobile, took a picture and sent it to Boges.

It suddenly darkened. A cloud must have hidden the moon. I turned around to thank Winter for showing me the Angel. But she was nowhere to be seen. While I was photographing the Angel and sending it to Boges, she’d slipped away.

I could only hope she wasn’t running straight to Sligo.

Liberty Square was quiet now. There were only a few people still on the streets. I was striding fast, my hood and collar pulled up around my face. I wanted to go back to St Johns Street to check out the derelict house. I couldn’t go back to sleep in the stormwater drain. Not tonight.

I’d crawled under the house but stopped when I heard voices and someone moving around.

I crept up to the verandah and snuck around the side of the house so I could peer through a crack in a boarded-up window.

Three people sat around drinking on the floor, the floor that I had spent so many hard nights on. Two men in shabby clothes and a younger woman with a gaunt face and stringy hair were sitting on my chairs, at my table. It was a hot night, but the woman was wearing long black mittens and had an old woollen shawl draped around her shoulders. They’d been through some of my food—there were empty tins rolling around. I didn’t dare interrupt. I didn’t want to stir up trouble. But I was really hungry and when I checked my pockets for money, I found I had hardly anything left of the money Boges had last given me.

I would have to find somewhere else to sleep.