Fiction Writer's Workshop (11 page)

Read Fiction Writer's Workshop Online

Authors: Josip Novakovich

First,

figure out what each character wants.

There are few moments in life like the one between Jack and his wife, when needs and desires are being laid bare. Jack wants his life to be the way it was before. His wife wants their life to become what it might be. In a rhetorical sense, they are trying to persuade each other. Even if their emotions are not fully on the surface in this scene (and this is an issue the writer can decide later), there should be a sense of urgency in the things they say. Adhering to the three-words rule, at least for this draft, should help add that.

Second,

avoid exposition.

Remember that most relationships are held together with tacit threads, things unspoken. Jack and his wife are married, so it's easy to see that they would know their history, that they would know the other's argument even as it's being made. But this advice holds true for most relationships and, notably, for most dialogue.

Consider this scene. A waiter comes to the table. A customer peruses the menu. Almost every element of the relationship is tacitly evident in the first words spoken: "What can I get you this evening?" They both know what's up. They understand and accept what's about to transpire. They both want things (the waiter, a clear order and generous tip; the customer, good service and hot food), but they don't state the entire circumstance either.

"Hello," said the waiter. "Have you had enough time to look at the menu, that piece of heavy-stock paper embossed with the full range of choices we offer in the three major categories— appetizer, entree and desserts—as well as a drink menu and sundries on the back there? I decided to see if you were ready to order now because I had a lull and I'm hoping to get this order started before I start on that guy's Caesar salad, which is an awful hassle since we use real anchovies and I have to peel open a new tin every time I make one. What a nightmare! At the very least, you might be ready to order a drink now from our full-service bar, which is right over there, just past that brass rail, next to the entrance."

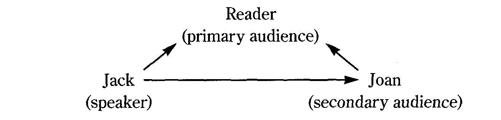

If the world were full of waiters like this, we'd all be ready to eat at home a lot more. But in some ways he's telling it like it is. The truth is, it's actually kind of nice that a person doesn't state everything he wants, everything he knows and everything both of you accept every time he speaks to you. Dialogue often becomes bloated with exposition, by the need to remind the reader of the basic tensions at work, to explain the circumstance beyond what is realistic and necessary. There's a false triangle many writers get trapped in. In this paradigm,

In the false triangle, the reader is the primary audience, the one for whom the words are being spoken. Thus, dialogue is shaped to the needs of the reader, rather than to those of the other character. Dialogue directed in this fashion sounds phony because it is phony. These aren't people talking. These are people "demonstrating" conflict or "actualizing" tension. The dialogue sounds wooden because its conceit is self-congratulatory. The writer who embraces this way of doing things suggests that the world he depicts is a cheap gauze, a mere filter for his ideas. If you are trying to write convincing, compelling stories, the relationship between the characters ought to be your primary concern.

the writer sees the characters talking for the benefit of the reader, as if the characters were speaking essentially to the reader.

What is the real model? Well, I hate models. They remain best written upon blackboards, where they can be erased, turned into dust by whoever happens along next. Still, there is probably a way to understand the relationship better by looking at a revised version of the false triangle. In this version, the energy of meaning runs from the reader, as secondary audience, toward both the character and the words themselves.

In this version, the meaning moves in more than one direction, and the reader is given some responsibility in the process. Here the reader looks at the conversations themselves for meaning, as well as the characters. The key is not to think of models as ways to succeed in crafting your dialogue. Remember, characters speak to each other, not to the reader.

Let's return to compression. Remember

tension means rhythm, and rhythm means interruption.

When you are compressing, you can pull a dialogue together by using the rhythm of the exchange to your advantage. Allowing characters to interrupt one another, to complete sentences, to repeat each other, is a way of reflecting the two items discussed earlier: what they want and what they know. When you are consciously boiling things down, the way you are in the act of compression, you have to rely on rhythm, interruption and flow within a dialogue. I'm telling you to go to five-word exchanges. You will get stuck. When you're stuck on which five words to use, have one character change the subject briefly or abortively. Or let one character cut the other one off in midstream. Or think of one as an echo for the other in a given moment. The exchanges in compressed dialogue ought to be like drums speaking to one another.

RHYTHM

Think in terms of beats. Read the following exercise, but while doing it, pound your left hand on the desk in beat with one character's lines, pound your right hand in beat with the other's. Use the number of words to represent the number of beats.

Left: You're drunk.

Right: I'll drive.

Left: Not with me.

Right: I'm hungry.

Left: Don't touch me.

Right: I'll drive.

Left: You'll drive.

Right: Yes.

Left: What do you want?

Right: Pancakes.

Left: Stop it.

Right: What?

Left: You smell.

Right: I've been drinking.

Left: I said—

Right: Just get in.

Left: You smell. Leave me be.

This has snap. Inferences can be drawn from it. It's not the whole story, absolutely not. But a lot of the story is in here, in this moment. Notice the techniques employed in this short space: repetition, interruption, changing the subject and echoing. There's very little exposition ("I've been drinking" qualifies, I suppose). There's also a clear sense of what each person wants, and not just in the moment, but perhaps beyond. The physical dynamic is clear enough. They are standing next to a car ("Just get in."). He might be coaxing (her "Don't touch me" line indicates his reaching for her to calm her). Her anger and his drunkenness are indicated in the way she echoes him ("You'll drive.") and the way he cuts her off.

Not every conversation is this punchy or brief. You have to recognize that. But remember what you are teaching yourself by clipping down to this kind of pow-pow exchange. Compression. You are mastering tight, highly expressive exchange. This is not banter either. These are people talking. By just barely saying anything, they are saying everything. Against your best instincts, you have to remind yourself that less is more, that you are meeting your obligations far more artfully by holding back than you would by lathering it on.

In Tobias Wolffs autobiography,

This Boy's Life,

are many examples of compressed dialogue. Look at the following dialogue without being introduced to the larger context of the book or the more particular one of this conversation. How much of it can you put together? The speaker is the narrator of the book, who likes to be called Jack.

I was up on the school roof with Chuck. He was looking at me and nodding meditatively. "Wolff," he said. "Jack Wolff."

"Yo."

"Wolff, your teeth are too big."

"I know they are. I know they are."

"Wolf-man."

'Yo, Chuckles."

He held up his hands. They were bleeding. "Don't hit trees, Jack. Okay?"

I said I wouldn't.

"Don't hit trees."

What sorts of things can you infer about these two? How old are they? What are they doing? What sort of relationship do they have?

I'm about to give you the answers, so think before you read on. All of the answers can be taken from this dialogue alone.

Well, they're kids, teenagers. Notice how Chuck ribs the narrator, the use of nicknames. They're on a roof, blowing each other grief. Chuck has been hitting trees. The sort of thing a boy does when he's fourteen or fifteen and has been drinking, which is what the two of them have been doing.

Now read the dialogue again, with the particulars of context better drawn out. Are things better focused? Maybe a bit, but essentially the dialogue is give-and-take, a back-and-forth, mostly reflective of an attitude. In some ways, it is a clean representation of how lost the narrator was at this moment in his life, when he felt cut off from his mother, isolated and alone in a tiny logging town and headed in all the wrong directions. It is not the whole story. There is no attempt to summarize the event. There is no long look at Chuck, no direct statement of how drunk he is. The words the boys speak do the work. Yet there is very little substance to what they say (which is surely part of the point) except for "Don't hit trees." How does this dialogue run? Repetition, interruption, echoing and changing the subject are all evident.

Here's another example of compressed dialogue, this one from Bobbie Ann Mason's "Shiloh." In this story, a working-class woman named Norma Jean goes through a crisis of self-identity and feels her marriage has left her trapped. At the end of the story, she and her husband, Leroy, picnic on the battlegrounds at Shiloh. There, surrounded by the monuments and forests, far from their trailer, Norma Jean says, "I want to leave you." The dialogue that follows is both predictable and surprising, and it stands as a good example of successful compression.

Without looking at Leroy, she says, "I want to leave you."

Leroy takes a bottle of Coke out of the cooler and flips off the cap.

He holds the bottle poised near his mouth but cannot remember to take a drink. Finally, he says, "No, you don't."

'Yes, I do."

"I won't let you."

'You can't stop me."

"Don't do me that way."

Leroy knows Norma Jean will have her own way. "Didn't I promise to be home from now on?" he says.

"In some ways, a woman prefers a man who wanders," says Norma Jean. "That sounds crazy, I know."

"You're not crazy."

Leroy remembers to drink from his Coke. Then he says, "Yes, you are crazy. You and me could start all over again. Right back at the beginning."

"We have started all over again," says Norma Jean, "and this is how it turned out."

"What did I do wrong?"

"Nothing."

"Is this one of those women's lib things?" Leroy asks.

"Don't be funny."

The cemetery, a green slope dotted with white markers, looks like a subdivision site. Leroy is trying to comprehend that his marriage is breaking up, but for some reason he is wondering about white slabs in a graveyard.

"Everything was fine till Mama caught me smoking," says Norma Jean, standing up. "That set something off."

What you might notice here is how much less evasion is evident in this one. The pattern of interrupting exists, but the two characters stay on the subject, dealing with it in an amazingly small number of exchanges. This is a literal compression; words are squeezed out of the lines, until the expression is at its barest and clearest. By moving things toward the most minimal exchange possible, you begin to discover the marvelous potential of economy in language. Get this down and then you can release. Compress and release. Compress and release. Sounds like a birthing class. But we'll get to that later.