Final Fridays (14 page)

Authors: John Barth

Â

BUT ENOUGH INDEED of this: The muses care not a whit about our personal profiles, and not much more than a whit about our politics; their sole concern is that we achieve the high country of Mounts Helicon and Parnassus, whether despite or because of where we're coming from, and this these two elevated spirits consistently did. The

paralleli

of their achievement are mostly obvious, the relevant anti-

paralleli

no doubt likewise. To begin with, both writers, for all their great sophistication of mind, wrote in a clear, straightforward, unmannered, non-baroque, but rigorously scrupulous style. “. . . crystalline, sober, and airy . . . without the least congestion,” is how Calvino himself (in the second of his

Six Memos

) describes Borges's style, and of course those adjectives describe his own as well, as do the titles of

all six of his Norton lectures: “Lightness” (

Leggerezza

) and deftness of touch; “Quickness” (

RapiditÃ

) in the senses both of economy of means and of velocity in narrative profluence; “Exactitude” (

Esatezza

) both of formal design and of verbal expression; “Visibility” (

VisibilitÃ

) in the senses both of striking detail and of vivid imagery, even (perhaps especially) in the mode of fantasy; “Multiplicity” (

MolteplicitÃ

) in the senses both of an

ars combinatoria

and of addressing the infinite interconnectedness of things, whether in expansive, incompletable works such as Gadda's

Via Merulana

and Robert Musil's

Man Without Qualities

or in vertiginous short stories like Borges's “Garden of Forking Paths”âall cited in Calvino's lecture on multiplicity; and “Consistency” in the sense that in their style, their formal concerns, and their other preoccupations we readily recognize the Borgesian and the Calvinoesque. So appealing a case does Calvino make for these particular half-dozen literary values, it's important to remember that they aren't the only ones; indeed, that their contraries have also something to be said for them. Calvino acknowledges as much in the “Quickness” lecture: “. . . each value or virtue I chose as the subject for my lectures,” he writes, “does not exclude its opposite. Implicit in my tribute to lightness was my respect for weight, and so this apology for quickness does not presume to deny the pleasures of lingering,” et cetera. We literary lingerersâsome might say malingerersâbreathe a protracted sigh of relief.

paralleli

of their achievement are mostly obvious, the relevant anti-

paralleli

no doubt likewise. To begin with, both writers, for all their great sophistication of mind, wrote in a clear, straightforward, unmannered, non-baroque, but rigorously scrupulous style. “. . . crystalline, sober, and airy . . . without the least congestion,” is how Calvino himself (in the second of his

Six Memos

) describes Borges's style, and of course those adjectives describe his own as well, as do the titles of

all six of his Norton lectures: “Lightness” (

Leggerezza

) and deftness of touch; “Quickness” (

RapiditÃ

) in the senses both of economy of means and of velocity in narrative profluence; “Exactitude” (

Esatezza

) both of formal design and of verbal expression; “Visibility” (

VisibilitÃ

) in the senses both of striking detail and of vivid imagery, even (perhaps especially) in the mode of fantasy; “Multiplicity” (

MolteplicitÃ

) in the senses both of an

ars combinatoria

and of addressing the infinite interconnectedness of things, whether in expansive, incompletable works such as Gadda's

Via Merulana

and Robert Musil's

Man Without Qualities

or in vertiginous short stories like Borges's “Garden of Forking Paths”âall cited in Calvino's lecture on multiplicity; and “Consistency” in the sense that in their style, their formal concerns, and their other preoccupations we readily recognize the Borgesian and the Calvinoesque. So appealing a case does Calvino make for these particular half-dozen literary values, it's important to remember that they aren't the only ones; indeed, that their contraries have also something to be said for them. Calvino acknowledges as much in the “Quickness” lecture: “. . . each value or virtue I chose as the subject for my lectures,” he writes, “does not exclude its opposite. Implicit in my tribute to lightness was my respect for weight, and so this apology for quickness does not presume to deny the pleasures of lingering,” et cetera. We literary lingerersâsome might say malingerersâbreathe a protracted sigh of relief.

Reviewing these six “memos” has fetched us already beyond the realm of style to other parallels between the fictions of Borges and Calvino. Although he commenced his authorial career in the mode of the realistic novel and never abandoned the longer narrative forms, Calvino, like Borges, much preferred the laconic short take. Even his later extended works, like

Cosmicomics

,

Invisible Cities

,

The Castle

of Crossed Destinies

, and

If on a Winter's Night a Traveler

, are (to use Calvino's own adjectives) modular and combinatory, built up from smaller, quicker units. Borges, more from aesthetic principle than from the circumstance of his later blindness, never wrote a novella, much less a novel.

6

And in his later life, like the doomed but temporarily reprieved Jaromir Hladik in “The Secret Miracle,” he was obliged to compose and revise from memory. No wonder his style is so lapidary, so . . . memorable.

Cosmicomics

,

Invisible Cities

,

The Castle

of Crossed Destinies

, and

If on a Winter's Night a Traveler

, are (to use Calvino's own adjectives) modular and combinatory, built up from smaller, quicker units. Borges, more from aesthetic principle than from the circumstance of his later blindness, never wrote a novella, much less a novel.

6

And in his later life, like the doomed but temporarily reprieved Jaromir Hladik in “The Secret Miracle,” he was obliged to compose and revise from memory. No wonder his style is so lapidary, so . . . memorable.

On with the parallels: Although one finds flavors and even some specific detail of Buenos Aires and environs in the corpus of Borges's fiction and of Italy in that of Calvino, and although each is a major figure in his respective national literature as well as in modern lit generally, both writers were prevailingly disinclined to the social/ psychological realism that for better or worse persists as the dominant mode in North American fiction. Myth and fable and science in Calvino's case, literary/philosophical history and “the contamination of reality by dream” in Borges's, take the place of social/psychological analysis and historical/geographical detail. Both writers inclined toward the ironic elevation of popular narrative genres: the folktale and comic strip for Calvino, supernaturalist and detective-fiction for Borges. Calvino even defined Postmodernism, in his “Visibility” lecture, as “the tendency to make ironic use of the stock images of the mass media, or to inject the taste for the marvelous inherited from literary tradition into narrative mechanisms that accentuate their alienation”âa tendency as characteristic of Borges's production as of his own. Neither writer, for better or worse, was a creator of memorable characters or a delineator of grand passions, although in a public conversation in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1975, in answer to the question “What do you regard as the writer's chief responsibility?” Borges

unhesitatingly responded, “The creation of character.” A poignant response from a great writer who never really created any characters; even his unforgettable Funes the Memorious, as I have remarked elsewhere, is not so much a character as a pathological characteristic. And Calvino's charming Qwfwq and Marco Polo and Marcovaldo and Mr. Palomar are archetypal narrative functionaries, nowise to be compared with the great pungent

characters

of narrative/dramatic literature. A first-rate restaurant may not offer every culinary good thing; for the pleasures of acute character-drawing as of bravura passions, one simply must look elsewhere than in the masterful writings of Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino.

unhesitatingly responded, “The creation of character.” A poignant response from a great writer who never really created any characters; even his unforgettable Funes the Memorious, as I have remarked elsewhere, is not so much a character as a pathological characteristic. And Calvino's charming Qwfwq and Marco Polo and Marcovaldo and Mr. Palomar are archetypal narrative functionaries, nowise to be compared with the great pungent

characters

of narrative/dramatic literature. A first-rate restaurant may not offer every culinary good thing; for the pleasures of acute character-drawing as of bravura passions, one simply must look elsewhere than in the masterful writings of Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino.

Attendant upon those “Postmodernist tendencies” aforecited by Calvinoâthe ironic recycling of stock images and traditional narrative mechanismsâis the valorization of

form

, even more in Calvino than in Borges. At his consummate best, Borges so artfully deploys what I've called the principle of metaphoric means that (excuse the self-quotation) “not just the conceit, the key images, the mise-en-scène, the narrative choreography and point of view and all that, but even the phenomenon of the text itself, the fact of the artifact, becomes a sign of its sense.” His marvelous story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” is a prime example of this high-tech tale-telling, and there are others. Borges manages this gee-whizzery, moreover, with admirable understatement, wearing his formal virtuosity up his sleeve rather than on it. Calvino, on the contrary, while never a show-off, took unabashed delight in his “romantic formalism” (again, my term, with my apology): a delight not so much in his personal ingenuity as in the exhilarating possibilities of the

ars combinatoria

, as witness especially the structural wizardry of

The Castle of Crossed Destinies

and

If on a Winter's Night a Traveler

. His extended association with

Raymond Queneau's OULIPO group was no doubt among both the causes and the effects of this formal sportiveness.

form

, even more in Calvino than in Borges. At his consummate best, Borges so artfully deploys what I've called the principle of metaphoric means that (excuse the self-quotation) “not just the conceit, the key images, the mise-en-scène, the narrative choreography and point of view and all that, but even the phenomenon of the text itself, the fact of the artifact, becomes a sign of its sense.” His marvelous story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” is a prime example of this high-tech tale-telling, and there are others. Borges manages this gee-whizzery, moreover, with admirable understatement, wearing his formal virtuosity up his sleeve rather than on it. Calvino, on the contrary, while never a show-off, took unabashed delight in his “romantic formalism” (again, my term, with my apology): a delight not so much in his personal ingenuity as in the exhilarating possibilities of the

ars combinatoria

, as witness especially the structural wizardry of

The Castle of Crossed Destinies

and

If on a Winter's Night a Traveler

. His extended association with

Raymond Queneau's OULIPO group was no doubt among both the causes and the effects of this formal sportiveness.

For reasons that will deliver me to the conclusion of this little homage, I regard Calvino as by far the finest writer in that lively Parisian group, which included the French/Polish Georges Perec and the American Harry Mathews, along with Queneau himself and a number of “recreational mathematicians” disporting with algorithmic narratives, or narrative algorithms. Calvino's skill at and delight in combinatory possibilities, a sort of structural

molteplicitÃ

, led him into enthusiasms that I cannot always shareâe.g., for the aforementioned Georges Perec, whose “hyper-novel”

La vie mode d'emploi

(

Life, a User's Manual

) Calvino calls “the last real event in the history of the novel thus far” (surely he means “latest,” not “last”) and which I myself find not only vertiginously ingenious but almost

merely

vertiginously ingenious. I read about a quarter of it, got the intricate idea (with Calvino's help), nodded my official approval, and could not force myself through the remaining three-quarters, confident as I was that the author would not miss a trick. Likewise, I have to confess, with Perec's algorithmic earlier novel

La Disparition

(translated as

A Void

), which so ingeniously manages not to use even once the most-used alphabetical letter in both French and English that at least some of the book's reviewers failed to notice that stupendous stunt. I shake my head in awe, but agree finally with the Englishman who said, vis-Ã -vis some other such feat, “It's a bit like farting

Annie Laurie

through a keyhole: damned clever, but why bother?”

molteplicitÃ

, led him into enthusiasms that I cannot always shareâe.g., for the aforementioned Georges Perec, whose “hyper-novel”

La vie mode d'emploi

(

Life, a User's Manual

) Calvino calls “the last real event in the history of the novel thus far” (surely he means “latest,” not “last”) and which I myself find not only vertiginously ingenious but almost

merely

vertiginously ingenious. I read about a quarter of it, got the intricate idea (with Calvino's help), nodded my official approval, and could not force myself through the remaining three-quarters, confident as I was that the author would not miss a trick. Likewise, I have to confess, with Perec's algorithmic earlier novel

La Disparition

(translated as

A Void

), which so ingeniously manages not to use even once the most-used alphabetical letter in both French and English that at least some of the book's reviewers failed to notice that stupendous stunt. I shake my head in awe, but agree finally with the Englishman who said, vis-Ã -vis some other such feat, “It's a bit like farting

Annie Laurie

through a keyhole: damned clever, but why bother?”

That question happens to be answerable, but I prefer to move on to Calvino's superiority, in my view, to such near-mere stunts; to his transcension of his own “oulipesque” enthusiasms; and to the close of this talk. At his Johns Hopkins reading in 1976, Calvino briefly

described the conceit of his

Invisible Cities

novel and then said, “Now I want to read just one little . . .” He hesitated for a moment to find the word he wanted. “. . . one little

aria

from that novel.” Said I to myself, “Exactly, Italo, and

bravissimo!

” The saving difference between Calvino and the other wizards of OULIPO was that (bless his Italian heart and excuse the stereotyping) he knew when to stop formalizing and start singingâor better, how to make the formal rigors themselves sing. What Calvino said of Perec very much applied to his own shop: that the constraints of those crazy algorithms and other combinatorial rules, so far from stifling his imagination, positively stimulated it. For that reason, he once told me, he enjoyed accepting difficult commissions, such as writing the

Crossed Destinies

novel to accompany the Ricci edition of

I Tarocchi

or, more radically yet, composing a story

without words

, to be the dramatic armature of a proposed ballet (Calvino made up a wordless story about the invention of dancing).

described the conceit of his

Invisible Cities

novel and then said, “Now I want to read just one little . . .” He hesitated for a moment to find the word he wanted. “. . . one little

aria

from that novel.” Said I to myself, “Exactly, Italo, and

bravissimo!

” The saving difference between Calvino and the other wizards of OULIPO was that (bless his Italian heart and excuse the stereotyping) he knew when to stop formalizing and start singingâor better, how to make the formal rigors themselves sing. What Calvino said of Perec very much applied to his own shop: that the constraints of those crazy algorithms and other combinatorial rules, so far from stifling his imagination, positively stimulated it. For that reason, he once told me, he enjoyed accepting difficult commissions, such as writing the

Crossed Destinies

novel to accompany the Ricci edition of

I Tarocchi

or, more radically yet, composing a story

without words

, to be the dramatic armature of a proposed ballet (Calvino made up a wordless story about the invention of dancing).

Â

TO COME NOW to the last of these

paralleli

: Both Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino managed marvelously to combine in their fiction the values that I call Algebra and Fire (I'm borrowing those terms here, as I have done elsewhere, from Borges's

First Encyclopedia of Tlön

, a realm complete, he reports, “with its emperors and its seas, with its minerals and its birds and its fish, with its algebra and its fire”). Let “algebra” stand for formal ingenuity, and “fire” for what touches our emotions (it's tempting to borrow instead Calvino's alternative values of “crystal” and “flame,” from his lecture on exactitude, but he happens not to mean by those terms what I'm referring to here). Formal virtuosity itself can of course be breathtaking, but much algebra and little or no fire makes for mere gee-whizzery, like Queneau's

Exercises in Style

and

A Hundred Thousand Billion

Sonnets

. Much fire and little or no algebra, on the other hand, makes for heartfelt muddlesâno examples needed. What most of us want from literature most of the time is

passionate virtuosity

, and both Borges and Calvino deliver it. Although I find both writers indispensable and would never presume to rank them as literary artists, by my lights Calvino perhaps comes closer to being the very model of a modern major Postmodernist (not that

that

very much matters), or whatever the capacious bag is that can contain such otherwise dissimilar spirits as Donald Barthelme, Samuel Beckett, J. L. Borges, Italo Calvino, Angela Carter, Robert Coover, Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, Elsa Morante, Vladimir Nabokov, Grace Paley, Thomas Pynchon,

et al

. . . . What I mean is not only the fusion of algebra and fire, the great (and in Calvino's case high-spirited) virtuosity, the massive acquaintance with and respectfully ironic recycling of what Umberto Eco calls “the already said,” and the combination of storytelling charm with zero naiveté, but also the keeping of one authorial foot in narrative antiquity while the other rests firmly in the high-tech (in Calvino's case, the Parisian “structuralist”) narrative present. Add to this what I have cited as our chap's perhaps larger humanity and in-the-worldness, and you have my reasons.

paralleli

: Both Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino managed marvelously to combine in their fiction the values that I call Algebra and Fire (I'm borrowing those terms here, as I have done elsewhere, from Borges's

First Encyclopedia of Tlön

, a realm complete, he reports, “with its emperors and its seas, with its minerals and its birds and its fish, with its algebra and its fire”). Let “algebra” stand for formal ingenuity, and “fire” for what touches our emotions (it's tempting to borrow instead Calvino's alternative values of “crystal” and “flame,” from his lecture on exactitude, but he happens not to mean by those terms what I'm referring to here). Formal virtuosity itself can of course be breathtaking, but much algebra and little or no fire makes for mere gee-whizzery, like Queneau's

Exercises in Style

and

A Hundred Thousand Billion

Sonnets

. Much fire and little or no algebra, on the other hand, makes for heartfelt muddlesâno examples needed. What most of us want from literature most of the time is

passionate virtuosity

, and both Borges and Calvino deliver it. Although I find both writers indispensable and would never presume to rank them as literary artists, by my lights Calvino perhaps comes closer to being the very model of a modern major Postmodernist (not that

that

very much matters), or whatever the capacious bag is that can contain such otherwise dissimilar spirits as Donald Barthelme, Samuel Beckett, J. L. Borges, Italo Calvino, Angela Carter, Robert Coover, Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, Elsa Morante, Vladimir Nabokov, Grace Paley, Thomas Pynchon,

et al

. . . . What I mean is not only the fusion of algebra and fire, the great (and in Calvino's case high-spirited) virtuosity, the massive acquaintance with and respectfully ironic recycling of what Umberto Eco calls “the already said,” and the combination of storytelling charm with zero naiveté, but also the keeping of one authorial foot in narrative antiquity while the other rests firmly in the high-tech (in Calvino's case, the Parisian “structuralist”) narrative present. Add to this what I have cited as our chap's perhaps larger humanity and in-the-worldness, and you have my reasons.

All except one, which will serve as the last of my anti-

paralleli

: It seems to me that Borges's narrative geometry, so to speak, is essentially Euclidean. He goes in for rhomboids, quincunxes, and chess logic; even his ubiquitous infinities are of a linear, “Euclidean” sort. In Calvino's spirals and vertiginous recombinations I see a mischievous element of the non-Euclidean; he shared my admiration, for example, of Boccaccio's invention of the character Dioneo in the

Decameron

: the narrative Dionysian wild card who exempts himself from the company's rules and thus adds a lively element of

(constrained) unpredictability to the narrative program. I didn't have the opportunity to speak with Calvino about quantum mechanics and chaos theory, but my strong sense is that he would have regarded them as metaphorically rich and appealing.

paralleli

: It seems to me that Borges's narrative geometry, so to speak, is essentially Euclidean. He goes in for rhomboids, quincunxes, and chess logic; even his ubiquitous infinities are of a linear, “Euclidean” sort. In Calvino's spirals and vertiginous recombinations I see a mischievous element of the non-Euclidean; he shared my admiration, for example, of Boccaccio's invention of the character Dioneo in the

Decameron

: the narrative Dionysian wild card who exempts himself from the company's rules and thus adds a lively element of

(constrained) unpredictability to the narrative program. I didn't have the opportunity to speak with Calvino about quantum mechanics and chaos theory, but my strong sense is that he would have regarded them as metaphorically rich and appealing.

Â

DID THESE TWO splendid writers ever meet?

7

Calvino's esteem for Borges is a matter of record; I regret having neglected to ask Borges, in our half-dozen brief conversations, his opinion of Calvino. My own esteem for both you will by now have divined. In Euclidean geometry,

paralleli

never meet, but it is among the first principles of non-Euclidean geometry that they

do

meetânot in Limbo, where Dante, led by Virgil, meets the shades of Homer and company, but in infinity.

7

Calvino's esteem for Borges is a matter of record; I regret having neglected to ask Borges, in our half-dozen brief conversations, his opinion of Calvino. My own esteem for both you will by now have divined. In Euclidean geometry,

paralleli

never meet, but it is among the first principles of non-Euclidean geometry that they

do

meetânot in Limbo, where Dante, led by Virgil, meets the shades of Homer and company, but in infinity.

A pretty principle, no? One worthy of an Italo Calvino, to make it sing.

Â

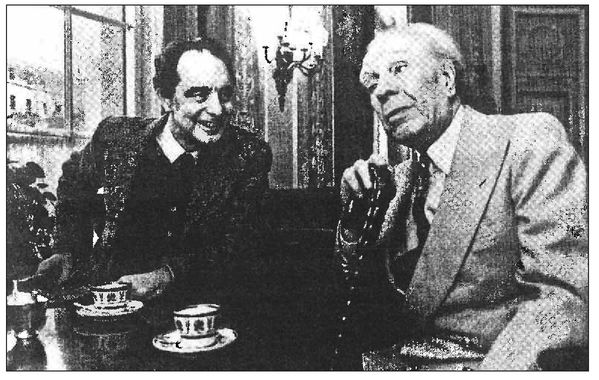

Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges. From

Album Calvino

, ed. Luca Baranelli and Ernesto Ferrero (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1995).

Album Calvino

, ed. Luca Baranelli and Ernesto Ferrero (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1995).

Other books

Adventures of a Sea Hunter by James P. Delgado

Mountain Woman Snake River Blizzard by Johnny Fowler

Eternal Darkness, Blood King by Gadriel Demartinos

Wintertide by Linnea Sinclair

The Token 7: Thorn (A Token Novel) by Eros, Marata

The Cure of Souls by Phil Rickman

Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms by Anita Heiss

The Dragon in the Sea by Frank Herbert

DR08 - Burning Angel by James Lee Burke