Final Fridays (33 page)

Authors: John Barth

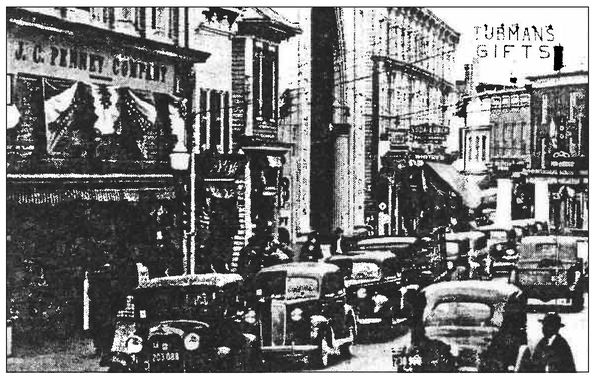

We'll get to thatâthough I don't recall our ever asking whence the nickname, either, which he carried from boyhood. Meanwhile it's 1922: The young shopkeeper meets and marries a local young milliner working in a hat-shop a few doors down from the Candyland; they move into a two-story white clapboard house next door to his parents, one block from the broad Choptank River and the hospital where over the next several years their children will be born, and where nearly 60 years later, still a resident of that house, at age 85 he'll breathe his last. Through the intervening half-dozen decades, despite a youthful sinus infection that in those pre-antibiotic days left him severely hearing-impaired for the rest of his life, he thrived in the small town and marsh-rich rural county that he had no interest in leaving (told by his doctor that the only hope for relief from his chronic sinusitis was a less humid climate, Dad replied that he'd rather be sick on the Eastern Shore than healthy anywhere else). He was gregarious, outgoing, and community-spirited: In addition to storekeeping from morning till night six days a week every week of the year, he served as an elected judge of the Dorchester County Orphans Court every Tuesday afternoon for a record-breaking 44 years, was a devoted member of the town's volunteer fire company as well as an organizer of similar companies in the county's smaller towns, and an American Legionnaire who not only marched with his fellow veterans in Cambridge's annual Armistice Day parade but became the chief organizer of those elaborate events. By comparison to his life, mine (literary and academic) seems almost reclusively detached, its radius much wider but its rootsâin serial dwelling-places from Pennsylvania and upstate New York to Maryland and south-west Floridaâless deep.

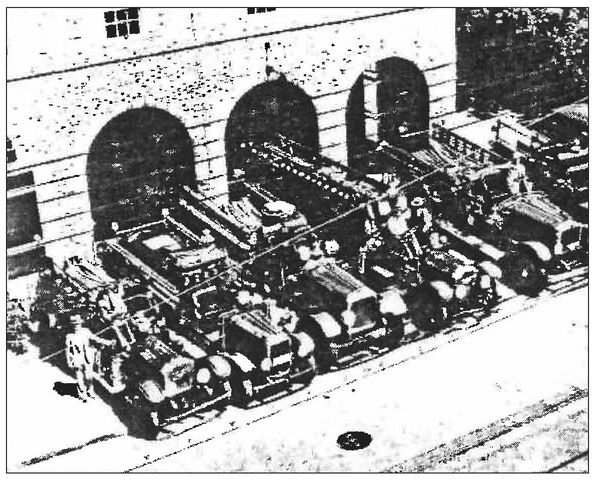

Because those volunteer fire companies, understandably, are tightly bonded social clubs as well as indispensable community-service outfits, in addition to their weekly meetings they have members-only banquets and fund-raising public barbecues and ham-and-oyster suppers. It was as the jocular after-dinner speaker at those banquets, in a dozen-plus venues around the countyâhis own beloved Rescue Fire Company and those others he'd helped organizeâthat Judge Whitey came into his own as an entertainer, in demand year after year: never a clown, but a humorist locally renowned for his joke-telling from at least the early 1940s until his death in February 1980, just a month before his scheduled appearance at the RFC's 37th Annual Memorial Banquet.

Â

Rescue Fire Company, Cambridge, MD, 1938.

âDoctor to patient: Your check came back. Patient: So did my arthritis.

Â

âhoneybee & horsefly / turnip in mouth / chicken with legs crossed / shad roe

My siblings and I, alas, never got to see our father do his number. Nor did he often tell jokes at home, where our conversation was typically good-humored but, owing at least in part to his deafness, seldom extended or really “personal”: witness those unasked questions about his nickname and his dropping out of high school. It was only as we went through his effects post mortem, in our middle age, that I found two small notebooks of handwritten joke-cues and 14 age-browned Whitey's Candyland envelopes containing more of the same on notepad-sized separate sheets and bearing the month and day, but seldom the year, of an upcoming gig and its location:

C'bge RFC, Taylors Island, Hoopers Island, Church Creek, Lakes & Straits, Neck District.

Some held a single sheet of perhaps nine cues; others five or six sheets with as many as 45 cues, occasionally annotated with a check, an X, or the word

used

. At times, evidently, he would “go around the table,” naming his firehouse comrades and addressing a joke to each (name followed by cue). In all, more than 200 jokes, fewer than half of them written out in full. While free of profanity, about three-quarters of them by my rough count are more or less ribald teasings of romance, courtship, marriage, infidelity, divorce, male and female anatomy, or some other aspect of sex (though a man of impeccable virtue, the Judge was not strait-laced):

C'bge RFC, Taylors Island, Hoopers Island, Church Creek, Lakes & Straits, Neck District.

Some held a single sheet of perhaps nine cues; others five or six sheets with as many as 45 cues, occasionally annotated with a check, an X, or the word

used

. At times, evidently, he would “go around the table,” naming his firehouse comrades and addressing a joke to each (name followed by cue). In all, more than 200 jokes, fewer than half of them written out in full. While free of profanity, about three-quarters of them by my rough count are more or less ribald teasings of romance, courtship, marriage, infidelity, divorce, male and female anatomy, or some other aspect of sex (though a man of impeccable virtue, the Judge was not strait-laced):

â“Am I the first man to sleep with you?” “If you doze off, you will be.”

Â

âMouse gets pregnant in A&P; didn't know about Safeway.

Â

âGirdle: keeps stomach in, boys out.

Â

â2 old maids: 1 trying to diet, 1 dying to try it.

About one in 10 is “ethnic” or otherwise minority-directed, their targets most often African-American (always by cue only, for some reason)

âcats on fence; colored woman

Â

âbaptize darkie; last thing remembered

Â

âcanning house; sleep with darkie

but also including Native Americans (

Indian says, “Chance.” Woman: “I thought all Indians said âHow.'” Indian: “I know how; just want chance.”

), Chinese (

Chinaman, food, flowers

)[?], Scots (

Scotsman comes to U.S.; has 1st baby; wants to tell folks back home. Cablegram = 4 words for $8; he writes “Mother's features, father's fixtures.”

), Jews (

Jewish couple, Abe & Becky, married 50 years, in bed

), and gays (

homosexuals & hemorrhoids = queers & rears = odds & ends

). The rest tease more “neutral” targets: doctors, judges, mechanics, farmers, animals, kids and parents, mothers-in-law. Offensive as one may find those “darkie” jokes in particularâtold, one presumes, prior to the Cambridge civil rights riots of the late 1960s, with its attendant sit-ins of Whitey's Candyland (an obvious

target) and other segregated businessesâit's worth remembering that they're an extension of the blackface minstrel,

Amos 'n' Andy

tradition popular among many blacks as well as whites from the 19th century to the mid-20th, and that unlike most other Southern eateries, Whitey's risked offending its white customers by serving blacks at least at the candy showcases and the soda fountain, as long as they didn't presume to sit down: the aptly named “Vertical Negro” policy, easy to tsk at from this remove, but considered liberal in that place and time.

Indian says, “Chance.” Woman: “I thought all Indians said âHow.'” Indian: “I know how; just want chance.”

), Chinese (

Chinaman, food, flowers

)[?], Scots (

Scotsman comes to U.S.; has 1st baby; wants to tell folks back home. Cablegram = 4 words for $8; he writes “Mother's features, father's fixtures.”

), Jews (

Jewish couple, Abe & Becky, married 50 years, in bed

), and gays (

homosexuals & hemorrhoids = queers & rears = odds & ends

). The rest tease more “neutral” targets: doctors, judges, mechanics, farmers, animals, kids and parents, mothers-in-law. Offensive as one may find those “darkie” jokes in particularâtold, one presumes, prior to the Cambridge civil rights riots of the late 1960s, with its attendant sit-ins of Whitey's Candyland (an obvious

target) and other segregated businessesâit's worth remembering that they're an extension of the blackface minstrel,

Amos 'n' Andy

tradition popular among many blacks as well as whites from the 19th century to the mid-20th, and that unlike most other Southern eateries, Whitey's risked offending its white customers by serving blacks at least at the candy showcases and the soda fountain, as long as they didn't presume to sit down: the aptly named “Vertical Negro” policy, easy to tsk at from this remove, but considered liberal in that place and time.

Where did all those jokes come from? Nowadays one's e-mail is awash with them, forwarded by friends from friends of their friends: a high-speed electronic Oral Tradition. Back then, my guess is that they came from bantering exchanges with friends and customers, from vaudeville acts (even small towns like Cambridge had live vaudeville into the 1930s: touring road companies and the celebrated Adams Floating Theatre), from radio shows like the aforementioned

Amos 'n' Andy

, and perhaps from the odd joke book in the Candyland's magazine rack or paperback bookshelf. Not impossibly Dad made up a few of them himself; if so, it's a talent that his son (like him, the younger of two) didn't inherit. (While I'm sometimes described as a comic novelist, the only joke that I can recall ever having invented I literally dreamed up, and was surprised not only to remember upon waking but to find not unamusing:

Restaurant waiter serves wine in glass with stem but no base. “How'm I supposed to set this glass down while I eat?” “Sorry, sir: We don't serve customers who can't hold their liquor. ”

)

Amos 'n' Andy

, and perhaps from the odd joke book in the Candyland's magazine rack or paperback bookshelf. Not impossibly Dad made up a few of them himself; if so, it's a talent that his son (like him, the younger of two) didn't inherit. (While I'm sometimes described as a comic novelist, the only joke that I can recall ever having invented I literally dreamed up, and was surprised not only to remember upon waking but to find not unamusing:

Restaurant waiter serves wine in glass with stem but no base. “How'm I supposed to set this glass down while I eat?” “Sorry, sir: We don't serve customers who can't hold their liquor. ”

)

More to the point, what

about

all these jokes and joke-cues? Their most-often-fragmentary natureâ

prodigal son / fish heads /

rabbit sausageâ

reminds me not only that I never got to see and hear the fellow do this particular one of the numerous things that he evidently did well indeed, but that in this as in who knows how many other ways I never got to

know

him: that to a greater or lesser extent our knowledge even of close kin is often fragmentary, inferred like a fossil skeleton or an ancient vase from whatever always-limited experience and shards of memory we have of them. For better as well as worse, perhaps: Just as well

not

to know all those “darkie” jokes, although in the context of that time and place they'd have been as inoffensively entertaining, at least to his all-white audience, as a burnt-corked Al Jolson singing “Mammy.” All the same, leafing through those time-browned, age-crisped cue sheets, like looking at his and Mother's photographs on my bookshelves (younger then than their son is now) or his Orphans Court name plaque on the shelf above my word processorâ

John J. Barth, Chief Judge

âinevitably makes me think, as the old Irish song laments, “Johnny, we hardly knew ye!”

about

all these jokes and joke-cues? Their most-often-fragmentary natureâ

prodigal son / fish heads /

rabbit sausageâ

reminds me not only that I never got to see and hear the fellow do this particular one of the numerous things that he evidently did well indeed, but that in this as in who knows how many other ways I never got to

know

him: that to a greater or lesser extent our knowledge even of close kin is often fragmentary, inferred like a fossil skeleton or an ancient vase from whatever always-limited experience and shards of memory we have of them. For better as well as worse, perhaps: Just as well

not

to know all those “darkie” jokes, although in the context of that time and place they'd have been as inoffensively entertaining, at least to his all-white audience, as a burnt-corked Al Jolson singing “Mammy.” All the same, leafing through those time-browned, age-crisped cue sheets, like looking at his and Mother's photographs on my bookshelves (younger then than their son is now) or his Orphans Court name plaque on the shelf above my word processorâ

John J. Barth, Chief Judge

âinevitably makes me think, as the old Irish song laments, “Johnny, we hardly knew ye!”

Nor you me, Dad, really; nor most of us one another, finally, beyond what souvenirs we've been given to imagine from, and what imagination we can bring to them:

ânude sunbather on skylight over dining room

Â

âbirth control; shower / ice: 400 lbs

Â

âBetter try a different speaker next time: Even a rooster gets tired of chicken every night.

Â

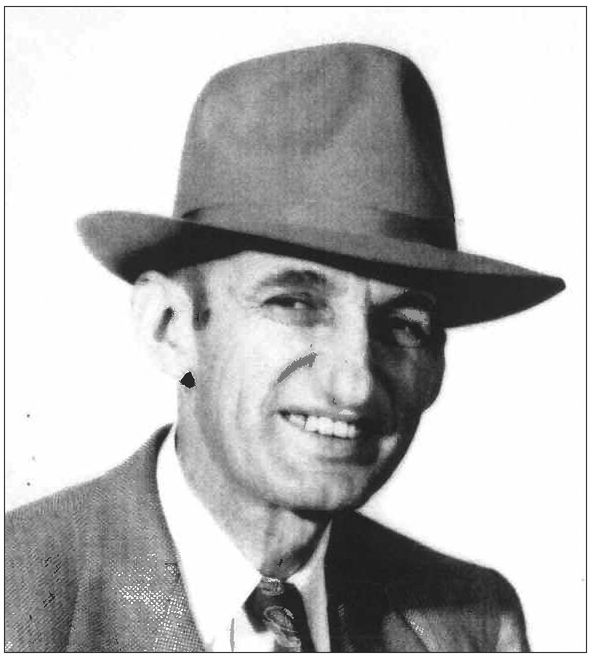

Judge John J. “Whitey” Barth, circa 1950.

Eulogy For Jill

A final farewellâthis one for Joan Derr Barth Corkran (May 27, 1930âAugust 7, 2009): my twin sibling Jill. Her German middle name was the maiden surname of our paternal grandmother, Anna Derr; my own Scotch-Irish middle name (Simmons) was our maternal grandma's married name (we kids never knew “Mommy Nora's” husband, nor to this day do I know what her maiden name was). Our nicknamesâsee belowâwere laid on us before our official given names, John and Joan. Given the circumstance of being a twin born under the zodiacal sign of Gemini and named after a nursery rhyme, it's to be expected that the motif of twins, doubles, alter egos, and the like may be found here and there in my fiction.

Â

Â

F

OR THE FIRST nine months of our joint existence, my twin sister and I were womb-mates. Conceived just before the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and waiting to be born in the first dark spring of the Great Depression of the 1930s, we were blissfully unaware of everything except, I suppose, each other's presence in that warm dark comfortable space. Even that double presence was somewhat more than our mother and her doctor were aware of in those days before ultrasound scans: Having delivered her of a healthy baby girl and thinking both his and her labors done, the doc checked outâand to

all hands' surprise, an hour and twenty minutes later an also-healthy baby boy followed, delivered by whoever happened to be on call.

OR THE FIRST nine months of our joint existence, my twin sister and I were womb-mates. Conceived just before the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and waiting to be born in the first dark spring of the Great Depression of the 1930s, we were blissfully unaware of everything except, I suppose, each other's presence in that warm dark comfortable space. Even that double presence was somewhat more than our mother and her doctor were aware of in those days before ultrasound scans: Having delivered her of a healthy baby girl and thinking both his and her labors done, the doc checked outâand to

all hands' surprise, an hour and twenty minutes later an also-healthy baby boy followed, delivered by whoever happened to be on call.

Sister first, brother second: I'll come back to that.

When the news was announced to our three-year-older brother Bill that he was no longer the family's only child, he gamely replied, “Now we have a Jack and Jill!”âand much followed from that. Having been

womb

-mates, for the next ten or twelve years my twin sister and I were

room

mates (in twin beds, appropriately) and though less genetically close than identical twinsâindeed, no closer genetically than any other pair of siblingsâI'd say we were otherwise about as close as non-Siamese twins can be. From kindergarten through elementary school in Cambridge, on Maryland's Eastern Shore, we attended the same classes, had the same friends, and were each other's best friend. We endured plenty of teasing from classmates about the “Jack and Jill” thing (including some memorably naughty versions of the nursery rhyme), but got used to it. When we took piano lessons, our teacher inevitably assigned us duets, wherein Jill always played the upper-keyboard melody part (

Primo

, considered appropriate for the girl, I guess), and Jack played

Secondo

, the lower-octave harmony-and-counterpoint part. Fine by me: It felt more manly down there in the bass clef.

womb

-mates, for the next ten or twelve years my twin sister and I were

room

mates (in twin beds, appropriately) and though less genetically close than identical twinsâindeed, no closer genetically than any other pair of siblingsâI'd say we were otherwise about as close as non-Siamese twins can be. From kindergarten through elementary school in Cambridge, on Maryland's Eastern Shore, we attended the same classes, had the same friends, and were each other's best friend. We endured plenty of teasing from classmates about the “Jack and Jill” thing (including some memorably naughty versions of the nursery rhyme), but got used to it. When we took piano lessons, our teacher inevitably assigned us duets, wherein Jill always played the upper-keyboard melody part (

Primo

, considered appropriate for the girl, I guess), and Jack played

Secondo

, the lower-octave harmony-and-counterpoint part. Fine by me: It felt more manly down there in the bass clef.

Other books

Drawn Into Darkness by Nancy Springer

One Shot at Forever by Chris Ballard

Deadly Abandon by Kallie Lane

At Grave's End by Jeaniene Frost

Jumped In by Patrick Flores-Scott

So Much to Learn by Jessie L. Star

Her Colorado Man by Cheryl St.john

Ms America and the Brouhaha on Broadway by Diana Dempsey

Mandy's He-Man by Donna Gallagher

The Rise (The Alexa Montgomery Saga) by Gordon, H. D.