Fire on the Horizon (15 page)

Read Fire on the Horizon Online

Authors: Tom Shroder

Crane operator Dale Burkeen, who would become one of eleven casualties, with his son, Timothy, and daughter, Aryan. (

Courtesy of Janet Woodson

)

Daun Winslow, one of the VIP visitors on April 20. (

U.S. Coast Guard

) John Guide, BP’s well team leader for the Horizon. (

U.S. Coast Guard

) Randy Ezell, senior toolpusher. (

U.S. Coast Guard

) Jesse Gagliano, technical advisor for cement work on the Macondo well. (

AP Photos

) Mike Williams, chief electronics technician. (

U.S. Coast Guard

) Stephen Bertone, chief engineer. (

AP Photos

)

The original Deepwater Horizon supervisory crew in 2001, as the rig floated in the harbor at Ulsan, Korea. Doug Brown is the fourth man from the left in the second row. Two of the victims of the blowout nine years later are also pictured: Donald Clark, first on the right, front row, and Jason Campbell, fifth from the right, second row. (

Doug Brown

)

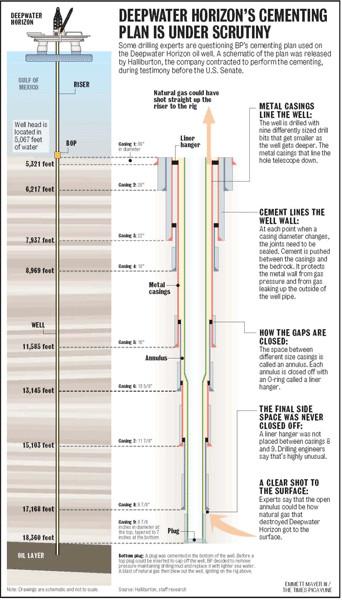

(

Times-Picayune

)

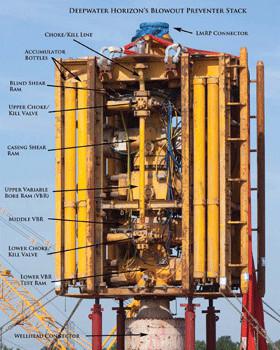

The blowout preventer. (

Robert Almeida

)

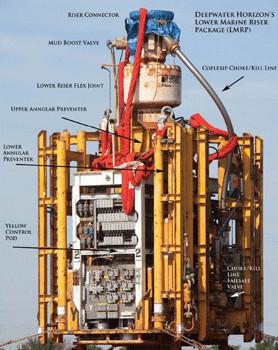

The lower marine riser package. (

Robert Almeida

)

With inexhaustible fuel from the blown-out well, the fires on the Horizon raged for thirty-six hours. (

Getty Images

)

The Horizon’s helipad is visible in the foreground, directly above the rig’s bridge, and just to the right of the empty lifeboat berths. (

Getty Images

)

On the morning of April 22, the combined effects of fire and firefighting overcame the Horizon’s ability to float. It listed, then capsized and plunged to the bottom. (

AP Photos

)

(

AP Photos

)

The gantry lifted the BOP off the hydraulic cart, then out toward the center of the moon pool, directly beneath the derrick, and held it there. It was the mirror image of a rocket preparing to launch. Instead of emerging from the gantry and soaring toward the moon, it would be descending into the moon pool, then launching into the inner space of the ocean.

While the BOP hung above the water, its connector pipe aiming toward the wellhead, the drilling crew had been readying the first section of riser pipe.

With its dynamic positioning system, the rig was astonishingly capable of keeping itself on location, but the stability couldn’t be perfect, given the ocean’s heaving waves and currents. The steel riser dangling five thousand feet below the rig would need flexibility to manage these forces. So at the top of the BOP, below the first section of the riser, the crew would install a coupling called a flex joint, a substantial steel and rubber coupling that allowed the rig to move off station by a certain amount without damaging the riser or BOP. The flex joint, which alone weighed several tons, was hooked to the top drive—the huge engine block that, during normal drilling operations, slid down the derrick, turning the drill as it drove deeper into the earth.

The top drive was operated by the driller from a small office directly beneath the derrick, called the drill shack. It used to be that the drill shack was a gritty place where the driller manipulated levers and foot pedals to control the top drive from a ratty chair, but in a fifth-generation rig like the Horizon, the driller sat in air-conditioned comfort at an ergonomically designed console,

overlooking the drill floor behind a wall of glass. He operated the top drive through the rig’s computer system using a joystick. On his computer screen he could see virtual dials and gauges that were hooked into the rig’s extensive sensory network and told him whatever he needed to know about what was happening on deck or in the well. His need to know was critical. The sensors could alert him to a well that was about to blow out, or one that was crumbling because of too much drilling pressure. It could also give him early warning of a malfunction in the dynamic positioning system.

Besides failure to anticipate a major storm, the two biggest threats to the system keeping the Horizon steadily above the well were either a sudden power blackout or a power surge. In a blackout, the engines would shut off and set the rig adrift. In rarer instances, a computer glitch or mechanical breakdown could ignite a “drive-off”—powering up one or more of the thrusters from 20 percent to 100 percent in an instant, pushing the rig off the well and threatening to rupture the riser.

If for any reason, the rig begins to move out of position, the system signals a warning. At a certain distance, a yellow light goes on—this is 50 to 60 feet from center in 5,000 feet of water. When the light flashes, the subsea engineer will stand by for an emergency disconnect, known as EDS. Drilling will stop and the drill pipe will be pulled up a little to make sure shear rams in the BOP have nice, smooth pipe to cut into rather than the thick joint between pipe sections. Then the driller will watch his panels. At 100 to 120 feet from center, the red light comes on. That’s when there’s no choice. The EDS button has to be pushed to prevent rupturing the riser.

Nobody wants to push the EDS button. A disconnect is expensive—it would take a day or two before the rig could reconnect

to the well and get back to work. But failure to disconnect can be even more costly. The BOP could be damaged or destroyed; the whole wellhead could tip over. It could cause a blowout.