First SEALs (4 page)

Authors: Patrick K. O'Donnell

W

OOLLEY AND

T

AYLOR

had their work cut out for them. They had a mission, but they lacked the necessary supplies and equipment to accomplish it. Finding an area suitable for training was just as difficult as finding boats. Practically overnight they had to build facilities for OSS operatives being trained in maritime operations and sabotage. “

It was necessary for Commander Woolley to beg, borrow, and almost steal” in order to be ready in time for the first class of OSS covert operations trainees.

Somehow Woolley found the funds, and the OSS took out a lease on April 1, 1942, for frontage of approximately ten thousand feet on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, several miles south of

Quantico, known as Smith Point. Because the land had no buildings to house the men or future supplies, they shipped in structures from an old Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at St. Stephens Church, Virginia. But the buildings were far from complete. Taylor and a small group of OSS men had to lend a hand erecting the structures. With hard work and dogged determination, they transformed 1,230 acres of mosquito-infested, waterlogged territory into a top-secret training facility codenamed “

Area D.”

“D” was in the middle of nowhere. There was no place for those constructing the facility to sit comfortably at night. According to one OSS officer, “

The barracks were too hot and the mosquitoes and ticks will eat [people] alive if they sit outdoors.” Initially OSS tightly controlled the use of the small fleet of Jeeps the men were issued, so no one could readily escape Area D. Compounding the misery, the nearest store was miles away, so they couldn't easily buy cigarettes to feed the nicotine habit that was pervasive among the American military at the time. One OSS officer opined, “

There is an argument that the men on Guadalcanal [the battle in the Solomon Islands that was raging at this time] and other places have a tougher life than my men but they are in the U.S.A., and are human enough to want a life for which they are fighting for.” Gradually, as the buildings were constructed and the government restriction on travel eased, life improved.

As the buildings went up, someone needed to guard the secret facility, but the OSS faced a severe shortage of military security personnel due to the war efforts. The Army unit assigned for security around Area D did not arrive in time for the first class of operatives, so the OSS improvised. In its habit of doing much with whatever resources it had, “

[f]our elderly and reliable local men were hired to act as watchmen and four [African Americans] were engaged to carry out mess duties.” Area D was finally ready to receive its first class of recruits to engage in covert OSS maritime training.

In addition to building the Area D facilities, the men also went to work repairing the rotting hulks that would serve as their training boats. Taylor not only helped with repairs but also acted as a scrappy supply sergeant, borrowing from Peter to pay Paul and doing everything from ordering sparkplugs to consulting with marine architects on ways to improve the vessels. Taylor rolled up his sleeves and got out his hand tools to make the continuous repairs the boats sorely needed. According to a note handwritten by Taylor, “I can't recall but presume that it [the part for one of the boats] was paid. It was for

Marsyl

, just before we took her down the river for good. We have the putty knife for the

Maribel

,” which he knew how to put to ample good use.

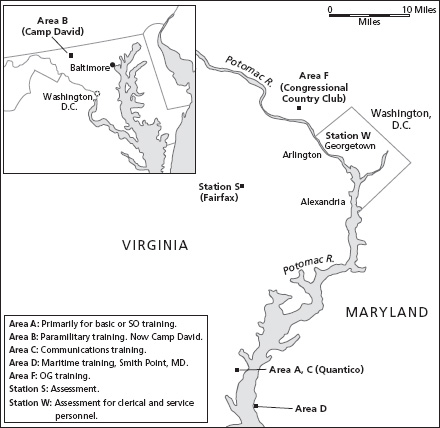

OSS TRAINING GROUNDS IN THE WASHINGTON AREA

An expert sailor, Jack Taylor had taken his own boat solo across much of the Pacific. With his incredibly well-honed boat-handling and nautical skills, Jack was a natural choice to become the chief instructor at Area D.

Joining Taylor as an instructor at D was Lieutenant Ward Evelyn Ellen. Dark-haired and well-built, Ellen had previously served with the Merchant Marine and the Navy, where he obtained the nautical skills that made him invaluable to the OSS. But unlike many of the other men recruited for the MU, Ellen was just an “

average Joe” and didn't share Taylor's gung-ho spirit about entering into the thick of the action, though he served his country well. His service record notes his excellent practical intelligence, stability, ability to work well with others, leadership capabilities, courage, integrity, and diligent work record as well as his “

picturesque language,” which the OSS perceived as a potential weakness. However, Ellen never felt he belonged in the OSS and longed for a less exciting assignment. One of Ellen's personal evaluations noted, “

Considerably disgruntled by a series of assignments for which he feels he was not fitted by training, experience, or interest, he wishe[d] to leave OSS and return to the Merchant Marine or Navy. He was assigned to OSS involuntarily and without any knowledge of the objectives or functions of the organization, and perhaps for this reason found the operations too âdramatic,' the duties too varied, and the periods of

inactivity too frequent.” Despite some perceived shortcomings, Ellen proved to be an excellent operator who would be integral to many of the MU's early activities.

B

Y EARLY

S

EPTEMBER

1942,

the first class of students arrived at Area D. The objective of the school was “

to teach each student how to penetrate an enemy-occupied territory by sea.” The course lasted two weeks and covered small-boat handling (including kayaks and canoes), navigation, tides, currents, charts, landing operations, and how to use explosives to sabotage shipping targets, such as ships, docks, warehouses, and other facilities. Each OSS student also left knowing how to crew and sail an antiquated sailboat that was moored alongside the

Maribel

and the

Marsyl

.

Many of the trainees' covert exercises carried a real element of danger. For example, in one session, “

Under the direction of the leader, the operatives go on to throttle the sentry and demolish the central station, about a half mile inland.” The mock exercise even included “

killing the enemy sentry with a hand grenade, which noise immediately raised the alarm.” Two Maritime trainees actually died in one of the exercises after their boat capsized; they drowned in the churning, dirty waters of the Potomac.

As chief instructor, Taylor did everything to make the night training as realistic as possible. It was wartime 1942, and in order to succeed the students needed to avoid detection by roving bands of armed shore patrols. In the frenzy of the burgeoning war efforts and after the attack on Pearl Harbor, national security was on high alert, and the military set up a series of security detachments along the Potomac to guard against enemy infiltration via U-boat. Instructors informed the students that the shore patrol was there to apprehend them and that they were amply supplied with “live ammunition.” The Maritime Authority documents noted, “

The students got small comfort from the rumor that [the shore patrol]

were poor shots.” Little did they know at the time, the “live” ammunition was actually blank rounds.

The backbone of the course was a covert night-landing operation at the end of the first week. Teams of students would attempt to make a clandestine insertion under the cover of darkness. Typically a four-man crew of trainees would set out in a small rubber or folding boat. Working in pairs, they attempted to land with the utmost of stealth at a very specific prescribed point. The trainees completed scores of exercises. A typical assignment read, “

1) You are to land within . . . a strip of beach in front of the camp about 2,600 yards in length. 2) Hide your boat effectively.” Throughout the exercises “

the instructors encouraged students to take risks.” Unsurprisingly, most of the candidates were “

of a daring type.”

Afterâhopefullyâavoiding the shore patrols, the candidates were to “

rendezvous at an abandoned house bearing 152°.” On other occasions they were sometimes directed to a small graveyard, which lent an eerie aura to the proceedings. One set of instructions read, “

POSITION OF CONCEALED RUBBER BOAT: In brush 10 yards directly east of tombstone marked âWilliam Mitchell,' which is in center of clump of trees approximately 150 yards north of camp and 50 yards east of beach.”

In these high-stakes, clandestine scavenger hunts, candidates had to gather a specific piece of intelligence. In the early training exercises the OSS began blending special operations insertion with intelligence gathering, which was groundbreaking by World War II standards. After collecting the information, the trainees had to once again avoid the dreaded shore patrol, quietly launch their craft, and vigorously row to meet their “submarine,” a role played by the aging and venerable

Marsyl,

which sat anchored in the river, awaiting their return.

THE RACE TO DESIGN A REBREATHER

I

NSPIREDâAND ALARMED

â

by the feats of the Italian frogmen, the Americans raced to catch up. Woolley, Taylor, Ellen, and the first men of the Maritime Authority anxiously pored over their enemy counterparts' accomplishments. “

Almost weekly reports come to OSS recounting exploits of maritime sabotage that constitute one of the most intriguing chapters of this war. They have served as a constant guide and incentive to the Maritime Unit.” The Italian frogmen had the expertise and technology to achieve spectacular success, and the major powers all formed underwater swimmer programs. What Woolley needed was a device for breathing underwater.

Woolley went to the Washington Navy Yard during the summer of 1942 to investigate the possibility of underwater swimming for the United Statesâthrough the OSS. Woolley, ever the visionary, saw the powerful potential of underwater combat:

With the possibilities of carrying out operations using the underwater swimming apparatus, what might be called a new field is opened up. Using the apparatus, it would be possible to carry or tow a much larger limpet [a magnetic mine] as would be preferable from a destructive point of view. A number of limpets would be placed against the hull of a ship to go off simultaneously. For this type of operations,

men specifically trained in the use of the equipment and good swimmers in practice would be desirable. I believe that using a submarine or a fast boat under cover of darkness, an approach could be made within a few miles of certain Axis-held harbors. From this point, a few miles out, operatives and explosives would be transferred to a new type of eight-man kayak. It would be carried in the vessel for that purpose. The eight-man kayak could then proceed using an on-board silent motor and paddling when necessary to avoid the question of noise to the harbor.

In order to make Woolley's vision a reality, the United States would need as-yet-undeveloped equipment that would allow swimmers to breathe underwater without releasing telltale bubbles. The race was on to create a closed-circuit device related to SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus)

*

that would allow swimmers to “rebreathe” their exhaled air underwater.