Flags of Our Fathers (2 page)

Read Flags of Our Fathers Online

Authors: James Bradley,Ron Powers

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Non-Fiction, #War

John Bradley never confided the details of his valor to Betty. Our family did not learn of his Navy Cross until after he had died.

Now Steve took my mother’s arm and steadied her as she walked up the thick sand terraces. Mark stood at the water’s edge lost in thought, facing out to sea. Joe and I saw a blockhouse overlooking the beach and made our way to it.

The Japanese had installed more than 750 blockhouses and pillboxes around the island: little igloos of rounded concrete, reinforced with steel rods to make them virtually impervious even to artillery rounds. Many of their smashed white carcasses still stood, like skeletons of animals half a century dead, at intervals along the strand. The blockhouses were hideous remnants of the island defenders’ dedication in a cause they knew was lost. The soldiers assigned to them had the mission of killing as many invaders as possible before their own inevitable deaths.

Joe and I entered the squat cement structure. We could see that the machine-gun muzzle still protruding through its firing slit was bent—probably from overheating as it killed American boys. We squeezed our way inside. There were two small rooms, dark except for the brilliant light shining through the hole: one room for shooting, the other for supplies and concealment against the onslaught.

Hunched with my brother in the confining darkness, I tried to imagine the invasion from the viewpoint of a defending blockhouse occupant: He created terror with his unimpeded field of fire, but he must have been terrified himself; a trapped killer, he knew that he would die there—probably from the searing heat of a flamethrower thrust through the firing hole by a desperate young Marine who had managed to survive the machine-gun spray.

What must it have been like to crouch in that blockhouse and watch the American armada materialize offshore? How many days, how many hours did he have to live? Would he attain his assigned kill-ratio of ten enemies before he was slaughtered?

What must it have been like for an American boy to advance toward him? I thought of my own interactions with the Japanese when I was in my early twenties. I attended college in Tokyo and my choices were study or sushi. But for too many on bloody Iwo there were no choices; it had been kill or be killed.

But now it was time to ascend the mountain.

Standing where they raised the flag at the edge of the extinct volcanic crater, the wind whipping our hair, we could view the entire two-mile beach where the armada had discharged its boatloads of attacking Marines. In February 1945 the Japanese could see it with equal clarity from the tunnels just beneath us. They waited patiently until the beach was chockablock with American boys. They had spent many months prepositioning their gun sights. When the time came, they simply opened fire, beginning one of the great military slaughters of all history.

An oddly out-of-place feeling now seized me: I was so glad to be up here! The vista below us, despite the gory freight of its history, was invigorating. The sun and the wind seemed to bring all of us alive.

And then I realized that my high spirits were not so out of place at all. I was reliving something. I recalled the line from the letter my father wrote three days after the flagraising: “It was the happiest moment of my life.”

Yes, it had to be exhilarating to raise that flag. From Suribachi, you feel on top of the world, surrounded by ocean. But how had my father’s attitude shifted from that to “If only there hadn’t been a flag attached to that pole”?

As some twenty young Marines and older officers milled around us, we Bradleys began to take pictures of one another. We posed in various spots, including near the “X” that marks the spot of the actual raising. We had brought with us a plaque: shiny red, in the “mitten” shape of Wisconsin and made of Wisconsin ruby-red granite, the state stone. Part of our mission here was to embed this plaque in the rough rocky soil. Now my brother Mark scratched in that soil with a jackknife. He swept the last pebbles from the newly bared area and said, “OK, it should fit now.”

Joe gently placed the plaque in the dry soil. It read:

TO JOHN H. BRADLEY FLAGRAISER FEB. 23, 1945 FROM HIS FAMILY

We stood up, dusted our hands, and gazed at our handiwork. The wind blew through our hair. The hot Pacific sun beat down on us. Our allotted time on the mountain was drawing short.

I trotted over to one of the Marine vans to retrieve a folder that I had carried with me from New York for this occasion. It contained notes and photographs: a few photographs of Bradleys, but mostly of the six young men. “Let’s do this now,” I called to my family and the Marines who accompanied us up the mountain as I motioned them over to the marble monument which stands atop the mountain.

When the Marines had gathered in front of the memorial, everyone was silent for a moment. The world was silent, except for the whipping wind.

And then I began to speak.

I spoke of the battle. It ground on over thirty-six days. It claimed 25,851 U.S. casualties, including nearly 7,000 dead. Most of the 22,000 defenders fought to their deaths.

It was America’s most heroic battle. More medals for valor were awarded for action on Iwo Jima than in any battle in the history of the United States. To put that into perspective: The Marines were awarded eighty-four Medals of Honor in World War II. Over four years, that was twenty-two a year, about two a month. But in just one month of fighting on this island, they were awarded twenty-seven Medals of Honor: one third their accumulated total.

I spoke then of the famous flagraising photograph. I remarked that nearly everyone in the world recognizes it. But no one knows the boys.

I glanced toward the frieze on the monument, a rendering of the photo’s image.

I’d like to tell you, I said, a little about them now.

I pointed to the figure in the middle of the image. Solid, anchoring, with both hands clamped firmly on the rising pole.

Here is my father, I said.

He is the most identifiable of the six figures, the only one whose profile is visible. But for half a century he was almost completely silent about Iwo Jima. To his wife of forty-seven years he spoke about it only once, on their first date. It was not until after his death that we learned of the Navy Cross. In his quiet humility he kept that from us. Why was he so silent? I think the answer is summed up in his belief that the true heroes of Iwo Jima were the ones who didn’t come back.

(There were other reasons for my father’s silence, as I had learned in the course of my quest. But now was not the time to share them with these Marines.)

I pointed next to a figure on the far side of John Bradley, and mostly obscured by him. The handsome mill hand from New Hampshire.

Rene Gagnon stood shoulder to shoulder with my dad in the photo, I said. But in real life they took the opposite approach to fame. When everyone acclaimed Rene as a hero—his mother, the President,

Time

magazine, and audiences across the country—he believed them. He thought he would benefit from his celebrity. Like a moth, Rene was attracted to the flame of fame.

I gestured now to the figure on the far right of the image; toward the leaning, thrusting figure jamming the base of the pole into the hard Suribachi ground. His right knee is nearly level with his shoulder. His buttocks strain against his fatigues. The Texan.

Harlon Block, I said. A star football player who enlisted in the Marines with all the seniors on his high-school football team. Harlon died six days after they raised the flag. And then he was forgotten. Harlon’s back is to the camera and for almost two years this figure was misidentified. America believed it was another Marine, who also died on Iwo Jima.

But his mother, Belle, was convinced it was her boy. Nobody believed her, not her husband, her family, or her neighbors. And we would never have known it was Harlon if a certain stranger had not walked into the family cotton field in south Texas and told them that he had seen their son Harlon put that pole in the ground.

Next I pointed to the figure directly in back of my father. The Huck Finn of the group. The freckle-faced Kentuckian.

Here’s Franklin Sousley from Hilltop, Kentucky, I said. He was fatherless at the age of nine and sailed for the Pacific on his nineteenth birthday. Six months earlier, he had said good-bye to his friends on the porch of the Hilltop General Store. He said, “When I come back I’ll be a hero.”

Days after the flagraising, the folks back in Hilltop were celebrating their hero. But a few weeks after that, they were mourning him.

I gazed at the frieze for a moment before I went on.

Look closely at Franklin’s hands, I asked the silent crowd in front of me. Do you see his right hand? Can you tell that the man in back of him has grasped Franklin’s right hand and is helping Franklin push the heavy pole?

The most boyish of the flagraisers, I said, is getting help from the most mature. Their veteran leader. The sergeant. Mike Strank.

I pointed now to what could be seen of Mike.

Mike is on the far side of Franklin, I said. You can hardly see him. But his helping young Franklin was typical of him. He was respected as a great leader, a “Marine’s Marine.” To the boys that didn’t mean that Sergeant Mike was a rough, tough killer. It meant that Mike understood his boys and would try to protect their lives as they pursued their dangerous mission.

And Sergeant Mike did his best until the end. He was killed as he was drawing a diagram in the sand showing his boys the safest way to attack a position.

Finally I gestured to the figure at the far left of the image. The figure stretching upward, his fingertips not quite reaching the pole. The Pima Indian from Arizona.

Ira Hayes, I said. His hands couldn’t quite grasp the pole. Later, back in the United States, Ira was hailed as a hero but he didn’t see it that way. “How can I feel like a hero,” he asked, “when I hit the beach with two hundred and fifty buddies and only twenty-seven of us walked off alive?” Iwo Jima haunted Ira, and he tried to escape his memories in the bottle. He died ten years, almost to the day, after the photo was taken.

Six boys. They form a representative picture of America in 1945: a mill worker from New England; a Kentucky tobacco farmer; a Pennsylvania coal miner’s son; a Texan from the oil fields; a boy from Wisconsin’s dairy land, and an Arizona Indian.

Only two of them walked off this island. One was carried off with shrapnel embedded up and down his side. Three were buried here. And so they are also a representative picture of Iwo Jima. If you had taken a photo of any six boys atop Mount Suribachi that day, it would be the same: two-thirds casualties. Two out of every three of the boys who fought on this island of agony were killed or wounded.

When I was finished with my talk, I couldn’t look up at the faces in front of me. I sensed the strong emotion in the air. Quietly, I suggested that in honor of my dad, we all sing the only two songs John Bradley ever admitted to knowing: “Home on the Range” and “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.”

We sang. All of us, in the sun and whipping wind. I knew, without looking up, that everyone standing on this mountaintop with me—Marines young and old, women and men; my family—was weeping. Tears were streaming down my own face. Behind me, I could hear the hoarse sobs coming from my brother Joe. I hazarded one glance upward—at Sergeant Major Lewis Lee, the highest-ranking enlisted man in the Corps. Tanned, his sleeves rolled up over brawny forearms, muscular Sergeant Major Lee looked like a man who could eat a gun, never mind shoot one. Tears glistened on his chiseled face.

Holy land. Sacred ground.

And then it was over. Time to board the vans and head back down Suribachi.

My brothers and I became like young boys in our last moments at liberty on the mountain. We scrambled down the slopes to collect souvenir rocks. Steve took photos of Joe, Mark, and me peeing over the side of Suribachi, a gesture several Marines had made on the day the flag was raised. Finally, we gathered the photographs I had retrieved from the van and tossed them into the wind over the mountainside. Images of our loved ones and of the six boys, distributed across the sacred ground.

Then I turned to face the Marine contingent, the uniformed strangers who had now become our friends—become part of our family.

“Thanks for being here,” I said to them. And then the Bradleys turned away, leaving the mountain, and soon the island, to its heroic ghosts.

Two

ALL-AMERICAN BOYS

All wars are boyish, and are fought by boys.

—HERMAN MELVILLE

BUT, NO. NOT GHOSTS. That was the point, I reminded myself, the point of my quest: to bring these boys back to life, or a kind of life, to let them live again in the country’s memory. Starting with my father, and continuing with the other five.

That is how we always keep our beloved dead alive, isn’t it? By telling stories about them; true stories. It works that way with our national past as well. Keeping it alive by telling its stories.

I’m not a professional scholar or researcher, but I figured that if I could somehow dig deep enough—find enough other boxes, in a manner of speaking—I might be able to achieve this. I knew that I could not do it alone. I would need other people, relatives and comrades of these six figures, to help me restore flesh and blood and bones to their dim outlines.

I started simply. I bought a book about Iwo Jima and read it. Then another. And another. I have since lost count.

I found names in those books; the names of the boys shoving that flagpole aloft.

Back in my office, I started to trace them. I wanted to talk to people who had known and loved them.

I phoned city halls and sheriff’s offices in the towns of the flagraisers’ births and asked for leads that would put me in touch with any of their relatives. I dialed the numbers, often with my heart in my throat. I waited through the rings for that first “Hello?” from a widow, or a sister, or a brother of one of the boys whose hands had gripped that pole on Suribachi.

It would take them a moment to comprehend who I was and why I was calling. But inevitably they opened up—as they had not opened up to phone calls from strangers, or to the press.

These calls, these conversations began to consume my days. Then my weeks, and months. Entire seasons. I widened my phone searches to include living veterans of Iwo Jima. I wanted their memories, too.

I had to take on a business partner to ease the workload at my company so that I could spend more time in this search for the six boys’ pasts. Eventually I began to travel to the places where they had lived.

As you read this, I am probably still searching. I will probably never stop.

But I have found most of what I wanted to know.

I wanted to know them as Marines, as fighting men who were also comrades. But more than that, I wanted to know them as boys, ordinary shirttail kids before they became warriors.

I wanted to know their family histories. And I wanted to know how “The Photograph” affected their families’ lives down into the present time. As a flagraiser’s son who had lived in the uneasy shadow of that photograph—a shadow cast by an image that itself was never visible in our household—I knew something about its lingering power within a family. I hungered to know what the Bradley household might have had in common with those of the other five.

The questions I asked generated many tears. But they opened up some bright, glowing chambers of the past as well.

The whole topic of boyhood, for example. Here was a many-faceted realm I had not quite expected to enter, but one that gave me endless fascination nonetheless: the lost realm of American boyhood in the years just before the Second World War.

Most of them, after all, were scarcely out of boyhood when they enlisted. Their lives up until then had been kids’ lives: hunting, fishing, paper routes; the movies, adventure programs on the radio, altar duties at church; first wary contact with girls. And, since money was scarce, helping out in their fathers’ businesses and tobacco fields; lending a hand in the coal mine, at the mill.

Hard times aside, the 1930’s was a terrific decade to be an American boy, whether in the hills of Kentucky or on the gridirons of south Texas or astride the carnival calliope in small-town Wisconsin. Boyhood then was a deeply textured universe all its own, a universe of possibility and hope.

An American boy’s life in the thirties, whether at work or at play, was about connection and community in ways that are hard to imagine today. It was about dreams, vivid and optimistic dreams of a future as radiant as Buck Rogers’s cosmos. As such, these dreams provided powerful incentives for courage and loyalty in battle in the minds of thousands of ex-boys in uniform—boys very much like the figures in the photograph.

They were so different, these six: the whooping young Texas cowboy astride his white horse; the watchful Arizona Indian on his reservation; the happy-go-lucky Kentucky hillbilly skinny-dipping in the Licking River; the serious Wisconsin small-towner walking with his third-grade sweetheart under the shade trees; the handsome New Hampshire smoothie checking his profile in the drugstore window; the sturdy Czech immigrant playing his French horn in the teeming Pennsylvania steel mill town. All forming their dreams of a future that was not to be.

And yet so similar.

They were nearly all poor. The Great Depression ran through their lives. But then so did football, and religious faith, and strong mothers. So did younger siblings, and the responsibility of caring for them.

Nearly all were described again and again as quiet, shy boys, yet boys whom people cared about.

Nearly all generated memories among brothers and sisters and childhood sweethearts that remained as crystalline at century’s end as at the moment they occurred.

And all of them together illuminated a great deal that was wonderful and innocent in an America that was soon to leave behind its own childhood forever.

John Bradley: Appleton, Wisconsin

My father’s earliest childhood images were dominated by exposed human hearts: the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Sacred Heart of Mary. Hearts at once human and divine, looming bloodred and out of scale from the open chests of figures who gazed with odd serenity from the large paintings in the Bradleys’ household. Iconic figures, among the most recognizable images in human history. Blood and redemption. Agony and healing. Life in death, and death in life. Sacrifice and salvation through faith.

Blessed Mother help us,

the grown-ups in young Jack’s household prayed, and

Sacred Heart of Jesus, I place my trust in thee,

to the holy presences represented in the paintings.

These images, with their rich, warm colors and vivid gestures, must have made a strong impression on the boy who became my father. Kind, lovely faces, reassuring and constant. The Jesus painting survived into the Antigo home of my own childhood. Symbols of the Catholic faith, an old and European Catholic faith now transplanted to the sunlit fields of 1920’s Wisconsin.

My father was born in 1923 in Antigo, the sturdy little town where he would return to sire his own family, and where he would die. He attended St. John’s Catholic School, where all eight of his own children would later enroll. But when he was seven, his father, James J. Bradley, moved the family about ninety miles southeast to Appleton, a graceful little city of 16,000 on the Fox River. Jesus and Mary and their visible sacred hearts made the journey with the family.

My dad’s mother, Kathryn, Germanic, anxious and worrying, the sister of a priest, had bought those images—standard-issue reprints, purchased at a religious-goods store—and hung them on the living-room wall. Kathryn was the religious worrier in the family; in fact she was the worrier-at-large. She worried about her children’s future in the faith, she worried about money, she worried:

What will the neighbors think?

As is so often the case with worriers, she worried about everything except what eventually went wrong.

James J. Bradley, my dad’s father, didn’t worry about much at all. A veteran of the trenches in World War I, he was a hardworking railroad man, a laborer in a coal depot, a bartender. An Irish-American good-timer, the kind of guy you’d call from the bar to settle a bet about some baseball statistic or other, and he’d give you the straight goods, off the top of his head.

A good man, all around, caught up in bad economic times. In Antigo, James Bradley, Sr., had proudly worn a railroad man’s uniform and plied his skills in a variety of jobs on the freight trains that crisscrossed the state. The Depression cut deeply into rail freight, and layoffs crippled the livelihoods of James and many of his fellow “Rails.” It was then that he uprooted his family for the more prosperous environs of Appleton.

There, he found work, and also had the misadventure of his career. During a shift as an engineer, he took a curve one day with a little too much throttle, and a boxcar filled with cabbages yawed and spilled all over the wayside. His buddies at the bar turned it into a hilarious local legend, and crowned him with the nickname “Cabbage.”

James Bradley struggled hard to rebuild his family’s middle-class comforts. Ever the optimist, he sired five children—my dad, “Jack,” was the second eldest—and ever the pragmatist, he expected each one, the boys especially, to help out with the household income. Jack and his older brother, James Jr., had newspaper routes throughout their childhoods. When they came home after making their collections each week, they often placed their money on the mantel. That money, perhaps along with the Blessed Mother, helped keep the family fed.

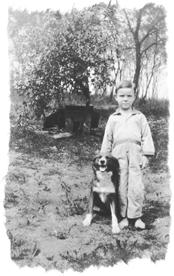

Like nearly every kid of his era, my father grew up wearing hand-me-downs, neat and clean clothes but hand-me-downs, from various cousins and uncles, and aspiring for more. He was a friendly boy, with a ready smile, but he never said much. Talking drew attention, the last thing he wanted. Later, a virulent case of acne deepened his pain at being observed.

He took refuge, with his pious mother, in the Catholic church. It was there, from his vantage point as altar boy, murmuring the Mass prayers in Latin, that he started to notice certain men who seemed to radiate a success and prosperity that belied the general hard times. One of these was his cousin, Carl Shutter. Carl wore handsome suits and fine neckties, and sold insurance for the prestigious Northwestern Mutual Life. Young Jack began to seek out men like Carl Shutter, ask their advice on matters of life. He noticed that these established businessmen—these lawyers and salesmen and bankers—liked him for that. It gave him a sense of his own developing style.

A particular category of businessmen caught his eye at church: the funeral directors of Appleton. These men, Jack thought, had a special way of walking up the aisle amid the incense-smell at Mass or during a funeral service: confident, in control, but always accessible. They seemed so at ease, so first-name familiar with everybody, and everybody seemed to know and respect them. The reason, he quickly came to understand, involved service: The funeral directors were not merely men selling a commodity; other than clergy, they were the ones most intimately in touch with the townspeople in their times of sorrow and need.

Jack Bradley understood service. That’s what an altar boy was, a “server.” And now here were these models of service well into adulthood. By his early teens, Jack Bradley was working part-time at an Appleton funeral home. He was going to be one of these respected, dignified men of service.

Meanwhile, life in Appleton, Wisconsin, seemed to lilt along almost in defiance of the Depression, or any other unwelcome intrusion. Everyone felt the pinch, but everyone took strength from the town’s resilient economic assets and its harmony of place. The town was caught in the lingering twilight of a prior time, a way of life less typical of the Depression than of the Belle Epoque. This era was fading fast in America; but in Appleton no one seemed to notice.

In those straw-hat years between the two world wars, Appleton seemed to embody just about everything that made America worth fighting and dying for. Its very name bespoke its atmosphere of ripe, unblemished enchantment.

Its terrain came out of some diorama of American plenty: low, rolling hills of soil rich and dark with wheat-growing fertility; bordering forests of thick hardwood trees, especially the cherished white pine, good for furniture-making and for paper stock. All of this sumptuous land cut through by a deep clear rushing river, the Fox, whose fish-filled waters had drawn generations of Indians and, later, the great tides of European immigrants, Dutch and German, flowing west in their caravans of prairie schooners.

Appleton was incorporated in 1853 with a population of 1,200, and its aura of quiet radiance, a place apart, never diminished over the ensuing century and a half. Demand for paper from its mills increased dramatically when an inventor in the metropolis to the south, Milwaukee, began to manufacture the typewriter in 1873.

The hardworking Middle-European settlers brought their burgher values to the town and the countryside around it. They made it a land of beer, cheese, bratwurst, and church spires; a land where education was valued, progress honored, government clean, houses neat, children obedient, homes happy, and churches sturdy and impressive.

Appleton boasted the first telephone in all Wisconsin, and the first house to be illuminated by incandescent light in any city beyond the East Coast. In 1911 President Taft brought it into the limelight again by biting into the four-foot-high “Big Cheese” that was Appleton’s entry in the National Dairy Show in Chicago.