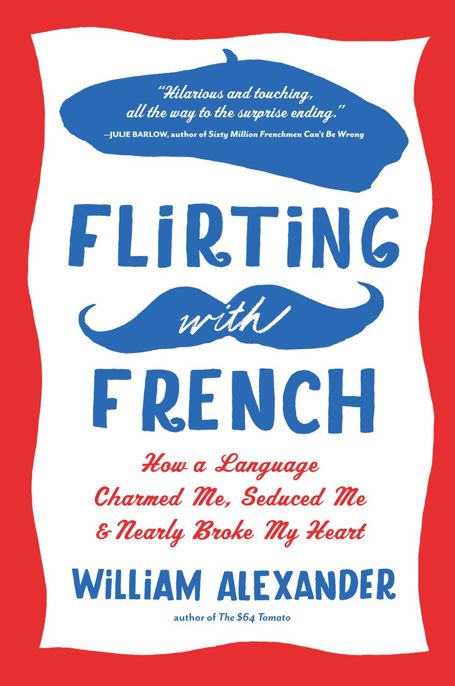

Flirting With French

Read Flirting With French Online

Authors: William Alexander

FLIRTING

FRENCH

How a Language

Charmed Me, Seduced Me

& Nearly Broke My Heart

by WILLIAM ALEXANDER

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2014

Also by William Alexander

52 Loaves: A Half-Baked Adventure

Th

e $64 Tomato: How One Man Nearly Lost His Sanity, Spent a Fortune, and Endured an Existential Crisis in the Quest for the Perfect Garden

For Guy

God was easier to understand than French.

—SINGER PEFM BAILEY,

explaining why she dropped a French class to take up theology

Contents

William the Tourist Meets William the Conqueror

French and the Middle-Aged Mind

Fruit Flies When You’re Having Fun

La France, Mon Amour

French, for me, is not just an accomplishment. It’s a need.

—

ALICE KAPLAN

,

French Lessons,

1994

Last night I dreamt I was French.

This mainly involved sipping absinthe at the window of a dark, chilly café, wrapped in a long scarf that reached the floor, legs crossed, Camus in one hand and a hand-rolled cigarette in the other. I don’t remember speaking French in the dream, and just as well, for in real life I once grandly pronounced in a Parisian restaurant, “I’ll have the ham in newspaper, and my son will have my daughter.”

I love France. I have from the first time I stepped onto its soil as a twenty-two-year-old with nothing more than a backpack and a Eurail pass, and subsequent visits over thirty-five years have only fueled my passion. What’s to love?

• A summer day along the Seine, the riverbank alive with groups of young people talking, singing, dancing, and sunning. Outrageously and playfully, the Seine has been transformed by Paris’s popular socialist mayor into a city-long beach, complete with sprinklers and tons of sand.

• Sitting at the counter of an astoundingly good restaurant alongside an elderly Frenchman and his white miniature poodle, for whom he has ordered a

bifteck,

rare. The server, who speaks no English, is practically begging me to order an off-the-menu special, which, as far as I can make out with my mostly forgotten high school French, is either young milk-fed pig or young pig marinated in milk, or both. The server prevails, and it is, as he knew it would be, the best meal I have ever eaten.

• Traveling from the Mediterranean to Paris by train at 190 miles an hour, the window turned into a fast-motion scroll of medieval villages, farms, and pastures.

• The owner-chef of a small village inn who, having just prepared and served us pigeon, rabbit, and foie gras, comes outside to help us clear an unexpected frost from our rental car windshield with the only tool available, her credit card.

• The hush of dawn at a medieval monastery, for a magical ten minutes perhaps the most beautiful spot anywhere on earth, as the Norman mist vaporizes before my eyes, lifting its veil from rows of sunlit apple and pear trees, their ripe fruit awaiting the attention of a monk’s hands and a chef’s knife.

• A hole-in-the-wall Latin Quarter brasserie you won’t find in any guidebook, whose waiter, a dead ringer for Teller (of Penn and Teller), skids around the sawdust-covered floor like Charlie Chaplin, balancing platters of

saumon à la crème

with crispy

pommes frites

(fifteen dollars, dessert included).

• A rainy afternoon with my wife at a Left Bank brasserie, watching the city scurry home, the drizzly streets an impressionist canvas come to life, Anne and I drunk on cold beer, on Paris, on love, happy as happy gets, neither of us speaking much, just enjoying the scene and realizing how lucky we are to love the same things, and Paris, and each other.

France does that to you.

Some Americans want to visit France. Some want to live in France. I want to

be

French. I have such an inexplicable affinity for all things French that I wonder if I was French in a former life (I’d like to think Molière, but with my luck, more likely Robespierre, which explains that persistent crick in my neck). I love French music and movies. I yearn to play

boules

in a Provençal village square while discussing French politics. To retire to a little pied-à-terre in the city or a stone

mas

in the country. To get to know and understand the people who still worship Napoleon, who consider “philosopher” a job title, who can be both maddeningly rigid and movingly gracious, and who can send their children away at age fourteen to be apprentices.

Most of all, I yearn to bring sound—speech—to that quiet café of my dream. I can’t be French if I don’t speak French. It’s time to stop yearning and start learning. True, at fifty-seven I’m well into what is politely referred to as late middle age, and my goal of fluency in French won’t come easily. But the way I look at it, next year I’ll be fifty-eight, and it won’t be any easier then.

C’est la vie.

Stiff Job

Pickering: we have taken on a stiff job.

—

HENRY HIGGINS

, on Eliza Doolittle,

Pygmalion,

1912

There aren’t too many places where you can hear a joke like this while standing in line for coffee: “So, I’m lecturing my class last week. In the English language, I tell them, a double negative forms a positive. However, in some languages, such as Russian, a double negative remains a negative. But there isn’t a single language, not one, in which a double positive can express a negative. And I hear a voice from the back of the room: ‘Yeah, right.’ ”

Certainly I’m not at Starbucks. This is the thirty-third annual Second Language Research Forum, or SLRF, which everyone here just calls “slurf,” at the University of Maryland. I’ve come in the hope of getting some insight and advice for the task that I am about to tackle: learning French—becoming

fluent

in French—at the age of fifty-seven. The opening speaker, Michael Long, a professor of second-language acquisition at the University of Maryland and the author of several books on the subject, has just told the 250 assembled linguists (although he seems to be looking directly at

me

) that only a “tiny, tiny minority” of postadolescent students will ever achieve near-native proficiency in a foreign language, and

none

will attain native proficiency. Long goes on to report in a matter-of-fact tone that the dimmest child will become far more proficient in his first language than the smartest adult in his second.

And I’m not even the smartest adult.

When Long opens the floor to questions, a woman strides purposefully to the microphone. Speaking in crisp British English, she demands to know why the success stories of thousands of adults in India who have successfully acquired near-native English proficiency (a definition that includes speaking without an accent) is not written about.

Long replies with a lengthy, academic answer involving studies of young women in third-world tribal areas who, when married into other tribes, reportedly picked up the language of their new tribe with ease—studies that, if confirmed, would make a mockery of all the perceived knowledge about second-language acquisition. “Yet when we looked into this reported phenomenon, there was no empirical data,” Long says. “It was all subjective interpretation by the observers. So while I am sympathetic to your question, I have to say we need hard data before we can report on it.”

This very

un

sympathetic reply infuriates the woman, who, while the rest of us heard “

Blah blah

research

blah blah

data,” heard “Liar!”

“Well, I can tell you for a fact that this is happening,” she shouts. “

I

am the data! I am one of these people! Yet as far as you are concerned, I don’t exist!”

And I thought this conference was going to be dull. Although it never again approaches the emotional drama of the introductory session. Many of the talks I sit through over the next two and a half days, featuring such topics as “Transfer Effects in the L2 Processing of Temporal Reference” and “Using Prosodic Information to Predict Sentence Length,” are Greek to me. This is mainly owing to my unfamiliarity with the subject matter, but the difficulty is compounded by the fact that the speakers are given only twenty minutes to present forty minutes of material, meaning that they all race through their PowerPoint slides, speaking at twice the rate of normal speech. This, I comment to a young Chinese graduate student during a break, seems a touch ironic, considering that this is a gathering of linguists, who should know better. She says, “Ironic? What does that mean?”

“Well,” I say, knowing I’m in trouble, “for example, it’s ironic that at a second-language acquisition conference you’ve asked me to explain a word that nearly all native speakers understand but that is nearly impossible to define. Isn’t that one of the core problems for the second-language learner?”

Her brow furrows and she squints at my name tag. “Where do you teach?”

“Oh, I’m not a teacher. I’m an IT director at a psychiatric research institute.”

This piques her interest. “You’re doing psychiatric research on language acquisition?”

“No. I’m learning French.”

I excuse myself and rush off to wolf down a muffin (better not attempt a word-for-word translation of

that

phrase into any language) on the way to the next session, where I hear that not only does the ability to acquire a second language become greatly diminished after adolescence, but the degradation continues linearly. That is, with each year, each

decade,

that I didn’t get around to learning French, the goalposts have moved further away. What was once a relatively easy fifteen-year field goal has become fifty-seven-nigh-going-on-fifty-eight years, even by NFL standards a long kick. If I had known this forty years ago, had realized back then that I was in a virtual now-or-never situation, would I have moved up the priority of this task? Attempted the kick before losing more yardage?

More bad news: I learn that I will always have a strong accent because any second language I acquire will be filtered through the matrix of my first. The presenters themselves, nearly all foreign born, often struggle with English during their talks, and I find myself thinking, Jeez, if the experts are having this much trouble, things don’t look good for me. I discover, to my great surprise, that Finns who move to Sweden at the age of

three

never attain native proficiency. Finns and Swedes? Isn’t that like New Englanders and Southerners? Don’t they already speak nearly the same language? You just shift around an umlaut or two. Certainly these two Scandinavian languages are far closer to each other than French and English!

This conference is looking like the worst pregame pep talk ever, the coach in the locker room warning, “Truth is, these guys are bigger and faster and smarter than we are, so forget winning; just try not to get hurt, boys.” Until, that is, I sit down to lunch with Vince Lombardi—actually Heidi Byrnes, a professor of German at Georgetown University and president of the American Association for Applied Linguistics. It soon becomes clear that I’ve come to the right woman.

I know this because she opens the conversation by telling me I’ve come to the right woman. The feisty sixty-six-year-old, with a bit of the rebel in her, tells me not to listen to all the naysayers present. “The general trope out there is, hey, by the time you’re fifteen or sixteen or seventeen, it’s over. I just don’t buy it—at all. It may be over, quote, unquote, whatever that means, for your phonetic features perhaps, but then you have to ask yourself, is that really the most important thing, that I am so completely indistinguishable as far as my accent is concerned? I don’t think so.”

The speakers do seem overly focused on this issue, yet even in the United States, a New Yorker sounds very different from a Californian. Furthermore, I point out, I love a woman with a French accent. If the actress Audrey Tautou spoke English

without

her gorgeous accent, she probably wouldn’t be a star here.

“There you go,” Byrnes agrees. “And yet, as we heard one more time today, that is an absolutely critical aspect of whether or not you ‘pass.’ ”

Perhaps the picture isn’t so bleak after all. As Byrnes and I continue discussing this gathering of professors and students of applied linguistics, I tell her I’m surprised by the highly theoretical nature of the presentations. I’ve found little here to guide me in my mission. “Excuse my naïveté,” I say, trying not to sound too snarky, “but I thought

applied linguistics

meant that at some point, we were going to apply it.”

Byrnes speaks with animation, but slowly, drawing out the occasional word for emphasis while adding meaning to her spoken words with her expressive hands—rubbing them together, pulling them apart, occasionally punctuating it all with a rich, hearty laugh. German-born, she is completely fluent in English, with traces of an accent—not German—that’s hard to place, more regional American, perhaps, than foreign. “You have a field of applied linguistics that over the last thirty years or so found it necessary to establish its scientific credentials. And the way to do that was by very strong theorizing.”

That’s all well and good, and having spent most of my adult life working in a research institute, I’m all for basic science, but, I wonder aloud, has all this theorizing and research (for example, tracking the eye movements of subjects as foreign words flash on a screen) yielded any practical results? “It seems to me we have a huge problem in this country,” I say. “I have a friend—a very sharp guy—who studied French from the fourth grade through his sophomore year in college. Eleven years of French. And he goes to Paris and finds out he can’t speak or even understand French. And this is not an uncommon story.” Byrnes nods vigorously. “Isn’t this a huge indictment of the state of language instruction in this country? This conference is in its third decade. After all this talk, all these papers and posters, after thirty years, have we made

any

progress in teaching foreign language?”

Byrnes tells me about the program they’ve developed in the Georgetown University German Department, where, by teaching German in a fashion in which “content learning and language learning can occur simultaneously”—in which every class attempts to connect the

learning

of a language with what you are going to be

doing

with the language—they have students coming in not knowing a word of German who are able to enroll in a German university after just four semesters.

Of course, Byrnes is speaking of eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds with their nimble brains. I ask her, “If you had me, not at eighteen, but now, at fifty-seven, when I can’t even remember where I put the car keys—” She doesn’t let me finish.

“I could do it!”

I feel like Eliza Doolittle talking to Henry Higgins.

“Really?”

“Absolutely! Because instead of thinking of you as a

deficit

learner—and you heard that, too, today, you’re a deficit critter because you’re past fifteen or past puberty—well, we’re not going to dwell on that. We’re not going to change that; that’s a

birth phenomenon.

”

I like that phrase. I’m not old, merely experiencing a “birth phenomenon.”

Instead of letting my age handicap me, Byrnes says, she would build on it. “Instead, I’m going to say, he’s a reasonably intelligent adult; let me take the cognitive abilities, the literate abilities, the interest that he has, and use those, and say, can I do something with them?—

precisely

because I know an adult learner is different from a child learner. So, rather than look at you as a deficit critter, I’ll say, look what he can bring to the enterprise.”

What can he—I—bring to the enterprise? My relative mastery of my first language, for one thing; I already know how language works. My maturity, for another. “You have enough of a sense of yourself, in contrast with some of our eighteen- or nineteen-year-olds, where this is a serious issue. They still are working on their identity. You

know

who you are.”

Last time I checked—about four hours ago—I was a fifty-seven-year-old laughing at the Three Stooges on the hotel TV, but best not to bring that up. She tells me that students who go abroad for an immersion program are often afraid to speak, for fear of embarrassing themselves. “But you see, for me,” Byrnes says, “I say, hey, what if they think, Gosh, she’s stupid, why does she sound like this? That’s not going to deeply affect my inner core of who I think I am; I can actually deal with that for the next five weeks. I can get something out of this. And I think you could, too.”

I’m almost convinced, but not quite. “I know that at my age, I could learn woodworking, I could learn some math. But French?”

“You have swallowed what is the cultural trope: ‘Just forget it, it’s a hopeless undertaking, you don’t have the memory, you can’t remember the silly words, it’s too complicated, all these dumb endings and pronunciation.’ No, no, no!”

Heidi Byrnes is my ray of hope in a storm of second-language gloom, so enthusiastic, so utterly convincing, that I feel like I’ve climbed the mountain and reached the oracle. I ask the big question, the one that has brought me to this conference: “How do I proceed? How do I learn French?”

She sighs, and I feel the air deflating from me. “The difficulty you’re going to have is you will essentially find no materials out there.”

There are a number of self-instruction products available, I point out, not mentioning by name a certain yellow box that has been sitting on my desk, unopened, for three months.

“Yes, but you see, for reasons that make a lot of sense, they have to go on the behaviorist approach, what they call communicative language teaching. Every one of them markets themselves like that. ‘We teach communication, and you will hear native speakers, situations in which you will learn how to function.’ ”

That actually doesn’t sound so bad to me, and Byrnes acknowledges, “There’s a lot to be said for that, for that will in fact enable you to do those sorts of things. By the same token, for us as an academic program, that kind of approach actually creates its own flat feeling because you come to see language and language learning in this purely instrumental way.”

I’ve heard enough presenters here to realize that they all consider learning a language from computer software comparable to learning the guitar from Guitar Hero, a bias you might expect from academics. Thus I take Byrnes’s warning with a grain of postgraduate salt and instead focus on the positive as she rushes off to attend the next session.

I am not a deficit learner. I don’t feel foolish when I screw up. I am a confident adult, and most of all, I know who I am.

Don’t I?