Floods 7 (3 page)

Authors: Colin Thompson

âI would say,' said Nerlin, pulling over, âthat whoever lives up here does not want visitors.'

âYou think?' said Betty.

âWell, nothing we've seen so far is any risk to us,' said Mordonna. âDon't forget we're witches and wizards. Bombs and diseases have no effect on us.'

âMaybe one of us should go ahead on foot to scout out the situation,' said Nerlin.

âOK, if you like,' said Mordonna. âOff you go, Parsnip.'

âSky falling down. Snip-Snip cold,' said the old bird as the clouds came down around them. âNeed hot soup.'

âYou go and see what's ahead. There's a good boy,' said Mordonna. âAnd when you get back I'll give you a big mug of mulligatawny soup, with real tawny in it, your favourite.'

âNo prob, like, er, man. Snip-Snip go see wassup,' said the bird, who had also got into the hippy thing.

He jumped down off the right-wing mirror and started walking up the track.

âWhat are you doing, you stupid bird?' Nerlin shouted after him.

âSnip-Snip go ahead on foot, like you said, man.'

âOK, OK. Well, there's been a change of plan,' said Nerlin. âGo ahead on wing.'

âRight off, dude man,' said Parsnip and flew into the cloud.

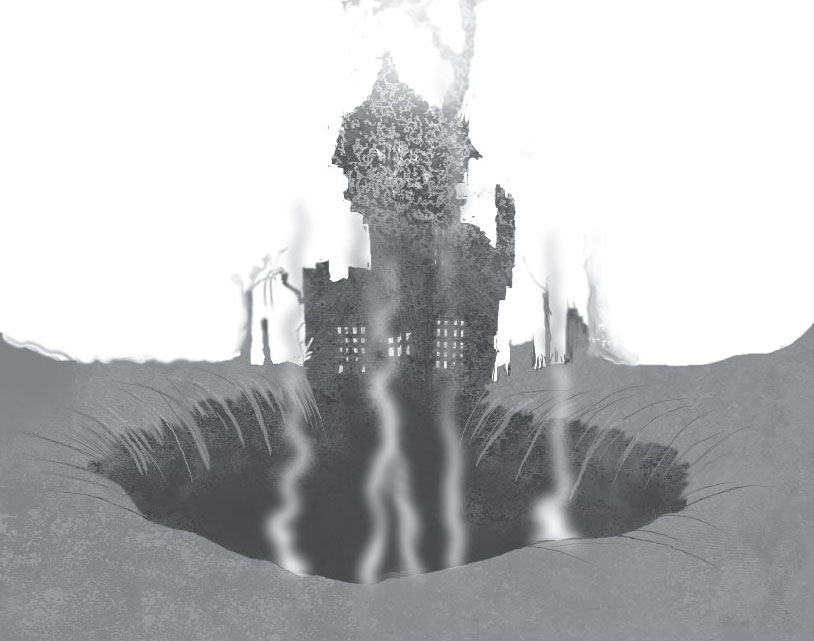

Meanwhile, the Hulberts had arrived back at Acacia Avenue to find that the worst had indeed happened. The Floods' houses at numbers 11 and 13 had not simply been burnt to the ground, they had been blasted into total oblivion. There were no bits of brick wall or smouldering armchairs. There was just a very deep, black, still smoking hole. The whole site was cordoned off with that black and yellow keep-out tape and a team of policemen and forensic scientists were digging up the garden.

The trouble was that the blast had disturbed some of the Floods' relatives who had been

buried there. Great-Aunt Blodwen's knees had gone flying through the bedroom window of a house across the street and Uncle Flatulence's rib cage had trapped a small child who happened to be walking by at the time. Cousin Vein, who had only been half dead when he had been buried, was now wholly dead and mixed up in the branches

of a big tree, from where he was dripping onto an ambulance.

So now the police were treating the whole thing as a murder investigation.

âWell, I always said they were a strange family,' said the man who had woken up to find bits of Great-Aunt Blodwen in bed beside him. He was standing

in the middle of the street with the rest of the neighbours, trying to see past the keep-out tape.

âSo did I,' said his wife.

âBut who would have thought they were mass murderers?' said the man.

âThey killed my cat,' said the man's daughter.

âNo they didn't,' said his wife. âIt was run over by a car. The Floods just ate it.'

âDon't be ridiculous,' said Mrs Hulbert. The Hulberts had arrived in their small rental car just as the road was blocked off by the police, so they were standing with the rest of the neighbours.

A creepy woman with a hat pulled down over her face and a very large pair of dark glasses came over to the Hulberts. She was holding a pencil and a notebook. It was the Hearse Whisperer.

âExcuse me,' she said. âI am from the

Morning Herald

. Can I ask you a few questions?'

âOh, er, um, we were away on holiday when this happened so we don't know anything,' said Mr Hulbert.

âReally, where?'

Fortunately, Winchflat, being a genius, had suspected the Hearse Whisperer might hang around looking for clues, so he had made each of the Hulberts a miniature Hearse-Whisperer-Warning-Device and implanted them under their armpits. If the Hearse Whisperer approached them the warning devices would start to tingle.

They were tingling like mad.

âMonte Carlo,' said Mr Hulbert at exactly the same time as Mrs Hulbert said, âLas Vegas,' and Ffiona said, âParis.'

âWe've been on a tour,' said Mr Hulbert.

âBlooga, blooga, amphibious,' said the baby Hulbert, Claude.

The Hearse Whisperer could tell they were lying, but she also knew that Mordonna must have inoculated each of them so that no matter what she did, they would never be able to tell her the truth even if they wanted to.

âSo you didn't know the people who lived in the bombed houses then,' she said.

âNo,' said Mr and Mrs Hulbert.

âHow do you know it was a bomb?' said Ffiona. âIt could have been a gas leak.'

âOr a lightning strike,' said Mr Hulbert.

âOr someone left the gas on,' said Mrs Hulbert. âAnd no, we did not know the Frauds.'

âThe Frauds?' said the Hearse Whisperer.

âWasn't that their name?' said Mrs Hulbert.

âBlooga, blooga, lighthouse,' said Claude.

âWell, little girl,' said the Hearse Whisperer, turning to Ffiona to try one last time to get the information she needed, âdid you have a lovely time at, um, where was it you said you'd been?'

âScotland.'

âExcuse me,' said the Hearse Whisperer. She walked over to a large tree and banged her head against it.

Because it was the evil Hearse Whisperer doing this and not an ordinary person, the tree came off the worst. All its leaves shrivelled up and died and several of its larger branches came crashing down, squashing a cat that was just about to leap on a small bird, and totally wrecking a police car.

Which just goes to show

, the Hearse Whisperer thought as she left,

that every cloud has a silver lining. Or in this case, two silver linings

.

âSnip-Snip bring love and peas, man,' said Parsnip when he arrived back at the Floods campervan an hour later.

âSo it's hippies,' said Nerlin, âand not a top secret military base.'

âChill out, wizardman,' said Parsnip. âIsallcool.'

They drove along the track, stopping to clear the rocks that had obviously been put there deliberately. Some of the rocks were so big it must have taken at least a dozen people to push them into place. Of course, for wizards, moving them

wasn't a problem. Each of them took it in turns transforming a rock into the vegetable of their choice. Everyone agreed that Betty's two-metre-tall cabbage was the best because when they drove the van into it, it rolled off down the road like a huge rolling cabbage.

The final obstacle on the road to Nowhere was a three-metre-wide ditch that had been dug across the road, but all it took to fill it in was a very small earthquake.

After that everything changed. They drove round a corner and the road began to go downhill. The clouds cleared and grass began to appear, then bushes then trees, then birds and softer, greener grass and softer, greener bushes and prettier birds until they found themselves in the most beautiful valley they had ever seen. It was the floor of a long-dead volcano, hidden away from the outside world like an enchanted place out of a fairy story.

Except for the scruffy old hippy who was standing right in front of their van.

He was smiling and holding out his open

hands in a love and peace sort of way, which usually means, âGive me a piece of everything you've got and I will love you.'

âWelcome to Nowhere, man,' he said. âI am Nameless.'

âNameless?' said Mordonna.

âYeah, man. I am Nameless because names are like possessions, they cage you. So when we all came here, we left our names out there.'

âHow many of you are there?' said Nerlin.

âThirty-seven, though we are one, man,' said Nameless.

âIncluding the women?' said Mordonna.

âWhat?'

âAnd you're all called Nameless?'

âYeah, man.'

âSo how do you know who is who?' said Mordonna.

âYeah, well, man, no one said it was easy being, like, alternative,' said Nameless.

âSo absolutely everyone here is called Nameless?'

âOh, no, man,' said Nameless. âThe Cool One is not called Nameless. He's called Sanguine. He's like, our guru.'

âWhat about your animals?' asked Betty. âAre they called Nameless too?'

âNo, man. The dogs are all called Dog and the cats are all called Cat, though the Cool One is thinking of changing their names because he says it's, like, stereotyping.'

âSo I suppose the chickens are all called Chicken?' said Betty.

âNo.'

âWhat are they called then?'

âEthel.'

âWhat, all of them?'

âYeah.'

âOK,' said Mordonna. âMoving on. Can we, like, chill here for a while?'

By now there were about fifteen Namelesses all gathered round. They nodded and did a bit of chanting and then said, âSure, man.'

âAnd remember,' said one of the Namelesses, who may or may not have been the same one they had been talking to earlier, âthere is, like, only one rule here and that is that there are no rules.'

âSo where can we park?' said Winchflat.

âOh, like, anywhere, man,' said Nameless.

âWell, I say anywhere and that's cool, but don't park over there by the orange yurt because that's, like, where the Cool One lives and he needs his space. And, like, down there is the Stamping Ground and that needs a lot of space for everyone to stamp. Same for the Sacred Chanting Place over there. And not under that tree, man, because there's a magpie's nest there and she's got, like, eggs and stuff so she needs her space. And not up there because that's, like, the Vegie Garden and, like, vegetables need their space too, man.'

âSo how about over there by the fence?'

âYeah, that's kind of cool, though of course the fence needs its space, man.'

âOK, where then?'

âWell, like, right where you are is cool.'

âIf you are all so free,' said Betty, âwhy do you have a fence? It's not as if there's any way to get in or out of the valley except by the track we came on and the fence doesn't actually fence anything.'

âWell, you might see it as a fence,' Nameless began.

âBecause it is,' said Betty.

âNo, but to us, it's, like, a symbol of the outside world where everyone is fenced in by authority and rules and stuff,' another Nameless finished.

âYeah, no rules, no rules,' the others chanted over and over again until one of them pointed out it was five past six and they were all late for the Six O'Clock Chant.

âLike, the Cool One gets totally freaked if anyone is late for the Six O'Clock Chant,' said Nameless.

âBut I thought you said there were no rules?' said Betty.

âNo, there aren't, man,' said a Nameless.

âExcept the Six O'Clock Chant rule,' said another.

âAnd the Eight O'Clock Chant rule,' said another.

âAnd the Midnight Chant rule,' said another.

âYeah, man, and of course the Dawn Chant rule,' said another. âWhich is actually around ten o'clock in the morning because the Cool One says

doing anything before then is, like, totally playing into the brainwashed work ethic thing.'

âAnd the three daily Stamping Rules.'

âAnd the Earwax Rule.'

âDon't ask,' said Mordonna, putting her hand over Betty's mouth.

âSo you're saying,' said Winchflat, âthat there are no rules unless the Cool One makes one up.'

âWell, no, man, because the Cool One doesn't make up rules. He just leads us along the path to Nirvana with his, like, extreme wisdom and guiding hand.'

âI bet he never does the washing up, does he?' said Mordonna.

âWell, no, of course not, man. That is a great honour awarded to all the chicks.'

âWhat's washing up, man?' said another Nameless as they ran off to chant.

Nerlin drove the van well away from the rest of the old vans, buses, yurts, assorted containers, sheds and tents and parked under the shade of a huge old tree.

âI expect it's not good to park here. All those dead leaves in the grass probably need their space,' said Valla and they all fell about laughing.

âAre we actually going to stay here?' said Betty. âThey're a bunch of complete idiots.'

âI know that, sweetheart,' said Mordonna. âBut this is probably the best place to hide while we work out what to do. The Hearse Whisperer would never suspect for a second that we'd be in a place like this.'

A dreadful wailing noise drifted down the valley as the Six O'Clock Chant reached its peak. It sounded as if every single one of the thirty-seven hippies was chanting in a different key. The cats and dogs ran for shelter. The chickens, although they had heard the chants dozens of times, all did their best to fly up into the safety of the nearest tree.

7

âNo wonder the cats are running away,' said Winchflat. âThat noise sounds like ten cats being strangled.'

âI wonder if they've got a manager,' said Satanella. âI reckon every witches' coven in the galaxy would buy a CD of that, if only to keep evil spirits from running away.'

âNevertheless,' said Mordonna, âthese strange people could be very useful.'

âYou have a plan?' said Nerlin.

âSeveral.'

It was dark by then, which meant none of the hippies could see what the Floods were doing. So they collected seventeen sticks, three paper bags, four gold rings and a partridge in a pear tree in a pile next to the van. Mordonna got out her best wand â not the one she used every day for boiling kettles and getting rid of spots, but her special occasion wand â and, with a couple of spells, she turned the pile into several bedrooms, a kitchen and the only bathroom in the valley.

The chanting stopped and the Floods

watched the group of flickering lights disperse as the Namelesses went back to their vans, tents and yurty things.

âThank goodness that's over,' said Nerlin.

âMind you,' said Valla, âthe vibrations have loosened my earwax a treat.'

As the family all sat round cleaning out their ears with blunt sticks,

8

Nameless came up to them.

âOK, like, people, the Cool One has summoned you into his Aura,' he said to Mordonna.

âReally?'

âYeah, it's, like, a seriously awesome invitation.'

âOh yes?'

âYeah, man. I mean, not everyone gets summoned into the Aura,' said Nameless. âI've never been there.'

âSo much for you all rejecting the petty privileged class system of the outside world,' said Mordonna. âNow you go and tell your so-called Cool One that if he wants to see me, he can come here.'

âOh, no, man, I can't possibly do that,' said Nameless, obviously terrified at the prospect.

âWhy not?'

âThe Cool One never comes out of the Aura Area.'

âWhat, never?'

âNo.'

âSo none of you have ever even seen him?'

âNo.'

âDo you mean that he never sets foot outside his yurt?' said Betty.

âOh no,' said Nameless. âHe comes out quite often.'

âSo you have all seen him then?'

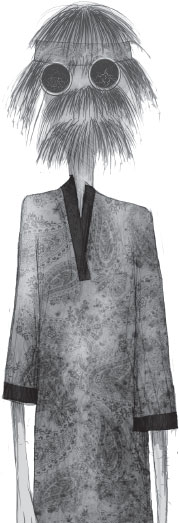

âNo, he comes out wearing his floating yurt,' said Nameless. âIt's like a personal tent that covers him from head to foot. Though my sister Nameless says that once, when she was lying on the grass in the pose of the dandelion, she saw one of his toes.'

âI wonder why he won't let anyone see him,' said Betty. âI bet he's really ugly.'

âNo, he says his aura is, like, so bright that if any of us saw it, it would strike us, like, totally blind.'

âYeah, right,' said Betty.

âWell, off you go and give him my message,' said Mordonna.

âNo, I can't,' Nameless whimpered. âPlease don't make me.'