Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (9 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Supporters retorted that physical frailty went with an innately superior refinement and sensitivity. But whatever the reason, it was invariably wealthier women, with too much time on their hands and too little to do, who sank in record numbers into chronically debilitating conditions such as hysteria, nervous depression, melancholia, and neurasthenia.

As a result, all sorts of innovative (i.e., horrifyingly sadistic) therapies were explored for the treatment of hysteria: heat, X-rays, bleaching, injections, electrical shocks. Doctors experimented with sticking leeches on the vulva, cauterizing the cervix, or even surgically removing the clitoris.

Funnily enough, none of these or other such treatments seemed to work. This included hysterectomy or ovariotomy (removal of the ovaries), a procedure that was first performed in Greece back in 120 B.C. and came roaring back into popularity at the height of the hysteria epidemic. Despite the 50 percent death rate, it was recommended not only for hysteria, but also for masturbation, uncomfortable menstruation, even too much libido. Patients were usually brought in by their husbands, and without a second thought doctors ripped out their healthy reproductive organs, striving for placid, postsurgical women in a sort of bizarre reproductive spin on the lobotomy.

Grim times, no? And so, this leads us back, finally, not only to Freud, but Hippocrates, Galen, and the rest of that ancient gang.

Could it be that they actually had a point? Was it really sex, or rather, the lack of sex, good sex, and the accompanying buildup of frustration that caused the thing called hysteria in the first place? Certainly, if it had been untold millions of men rather than women who routinely went without sexual release for years, we would have imagined not only hysteria but perhaps actual nuclear Armageddon to have erupted long ago. Whatever the actual problem, remedies such as those from ancient Greece once again became the go-to answer for female malaise.

Masturbation was viewed as something unwholesome and unnatural, while therapeutic stimulation was simply a means to an and, namely to relieve hysteria.

Consider the so-called water cure, popularized by Austrian physicist Vicenz Priessnitz and perhaps the biggest health fad of the mid-nineteenth century, lasting well until the 1920s. One may immediately conjure up quaint, sepia-tinted images of women cavorting in the cold surf in checked mob caps, stockings to the knee, and frilly bathing costumes, taking in the wholesome salt air. In fact, the cure consisted of high-powered water douches that were aimed squarely at the genital area for the express purpose of inducing orgasm.

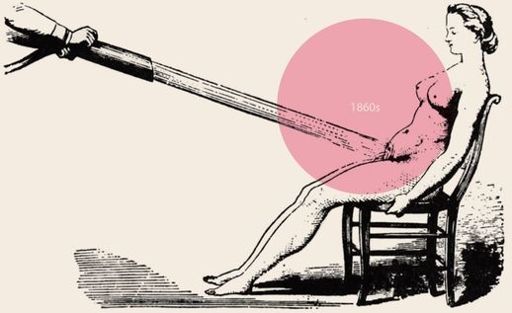

The water cure was an instant hit, and not just for the obvious reasons. At the time, having a hysterectomy was like playing Russian roulette with a loaded gun; it was a relief to have a medical procedure that entailed little risk other than getting one’s hair wet. And did it work? Consider R. J. Lane, who, when writing about a British spa in 1851, described the effects of the water cure thusly: “Persons are frequently known, on coming out of the douche, to declare that they feel as much elation and buoyancy of spirits, as if they had been drinking champagne.” Warm water or cold was sprayed from hoses hung high above or while patients were seated in tubs with jets pumping underneath. Water cures were soon all the rage, combining unprecedented sexual satisfaction with a wholesome-sounding vacation. Soon, women wanted more sessions, and then more, and more; one therapist said he had “difficulty in keeping them within rational limits.”

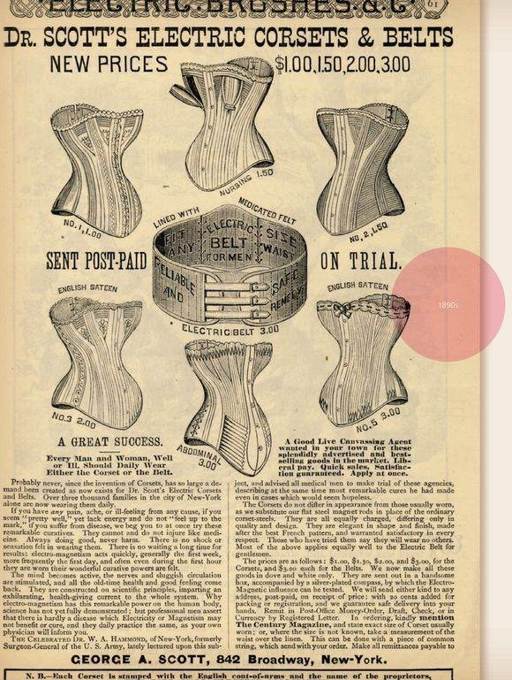

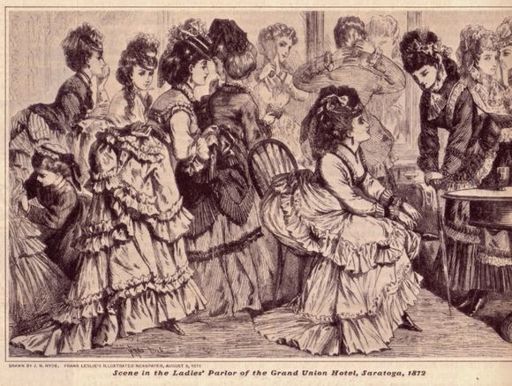

And how much of a surprise was that? In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was apparently both socially acceptable and medically approved for women to experience orgasm, but only in a controlled, deliberately nonsexual manner: in a doctor’s office, at a Saratoga Springs douching room, via a doctor-prescribed horseback ride or train trip over bumpy tracks (we’re not making this stuff up), or using a jolting chair or electrified rocking chair specifically invented for this purpose. Appointments were made, money changed hands, and sexual release was effected dutifully, as a form of therapy. Yet at the same time, masturbation remained strictly verboten.

Masturbation was not only a one-way ticket to hell, it was addictive and physically dangerous, as well. In his 1898 book, Confidential Talks with Young Women, Dr. Lyman Sperry didn’t mince words: “Every part of the body is abused and injured by it. You need not think it harmless at first because you do not feel those effects at first, for they come on so slowly that children are very often near death before they or their friends find out what is the matter with them; and if they do not die, the evil will cling to them and make them miserable through all their lives.” He also darkly insinuated that masturbators would swiftly become either insane or mentally retarded, and would very likely commit suicide.

This may all seem like a hopeless contradiction, and yet it makes a certain perverse sense. Western society has always assumed that women experience pleasure exclusively via the vagina, i.e., from intercourse with a man. Only vaginal penetration was considered stimulating to women, which is why the speculum and tampon were so controversial when they were introduced and the vibrator basically given a free pass. As a result, masturbation was viewed as something unwholesome and unnatural, while therapeutic stimulation was simply a means to an end, namely to relieve hysteria.

Even though hysteria was finally disavowed by the American Psychiatric Association in the early 1950s, the notion lingered on—now thought to be a result of a woman’s frigidity. Subtly, the prevailing attitude had shifted: the woman was no longer the passive victim of hysteria due to her uterus, but was instead somehow at fault due to her innate coldness and lack of interest in sex. From the 1954 Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex: “There are women who have‘grown cold’, women who, as a result of the deadly monotony of their marriage, have gradually lost their former undoubted potency and sometimes even their sexual desire. In such cases the medical man can do nothing. These emotionally dead people should be left to their dead, and our efforts should be devoted to the countless other unfortunate people whom it is still possible to help.”

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

There are dozens of conflicting explanations and theories explaining what hysteria was, what caused it and cured it, and even reasons for its great epidemic in the late nineteenth century. While many blamed frigidity, others blamed the physical constraints of fashion, the effects of diet, the need for children. Wherever the truth actually lies, we do feel that lying beneath the bogus, catchall unspecificity of the diagnosis, something was actually going on … something that brought genuine suffering to untold numbers of women. The question is, what was it exactly? And perhaps just as significantly, what brought it on?

We’re pretty sure that regular lack of sexual fulfillment may well have contributed to the unhappiness many women clearly felt for so many thousands of years. Yet can we get both political and conspiracy theorish for a moment?

Could what was historically called hysteria—widespread instances of clinical depression, unhappiness, anxiety, anger—have been a simple product not so much of sexual or maternal frustration, but of actual systematized oppression? After all, throughout history, women had no rights or autonomy, and were routinely barred from higher education, property ownership, the right to vote, careers. Could it be that when anyone is faced with such fundamental obstacles to happiness and self-actualization, even a whiz-bang orgasm isn’t enough to make things all better again?

By the mid-nineteenth century, change was in the air. The suffrage movement was on the rise, and women were fighting for higher education, as well. The possibilities were tantalizing, and yet the pressures brought by such change were enormous, taking their toll on women both mentally and emotionally. Margaret Sanger, the great birth control crusader, spent time incapacitated by deep depression. Jane Addams, social activist and the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, was also debilitated by depression for seven years. And Alice James, brilliant sister of novelist Henry and philosopher William, was chronically beset by nervous breakdowns that ruined her life.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, an early feminist writer, was diagnosed with hysteria in the late 1800s and was sent to Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, a hysteria specialist. He famously offered depressed men the “West Cure,” in which he urged them to go west, have rugged adventures in the wild, and then sit down and write about it. To his female patients, however, he prescribed the “Rest Cure”—which consisted of isolated bed rest for as long as two months, forced feedings, occasional electroshock therapy, and absolutely no reading and writing. Gilman later wrote damningly of her ordeal in her terrifying story, published in 1892, The Yellow Wallpaper, in which the heroine is literally driven insane by such a cure.

It wasn’t until the frighteningly recent 1950s that the diagnosis of hysteria, at least as it related to unexplainable female behavior, was finally, at long last, laid to rest, after one of the longest runs by any faux medical condition in history. By then, the field of psychology had far greater understanding about depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders, and so women suffering from any of those could now get a more concrete diagnosis than hysteria, as well as a more appropriate therapy. What’s more, by the 1950s, women had vastly more opportunities to be engaged in the world around them and challenged by their lives, strength, and interests. The 1950s may not have been a feminist mecca, but women had far more rights than ever before in history.

But here’s an interesting thought: hysteria, which was one of the most frequently diagnosed diseases in history, was officially removed from their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual by the American Psychiatric Association in 1952. And yet the following year, the term “premenstrual syndrome” was coined by Dr. Katharina Dalton. The National Health Service currently lists over 150 symptoms for PMS, including: feeling irritable and bad tempered, fluid retention and feeling bloated, mood swings, feeling upset or emotional, insomnia (trouble sleeping), difficulty concentrating, backache, muscle and joint pain, breast tenderness, tiredness, appetite changes, or food cravings.